— Topics —

Basic theory of gaining weight

2025.12.30

Biological Responses Driving Weight Rebound After Weight Loss

<Summary>

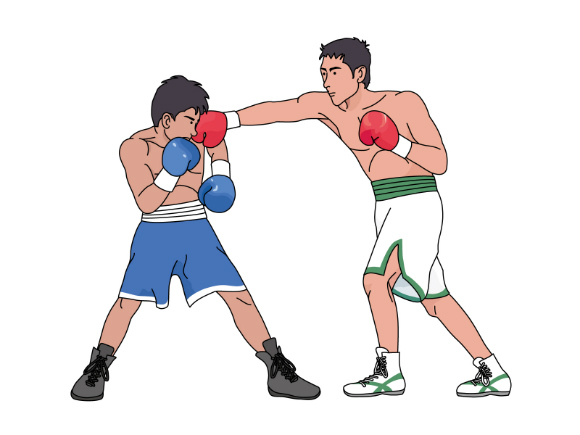

When individuals lose weight through calorie restriction, adaptive responses involving coordinated changes in metabolism, neuroendocrine function, autonomic regulation, and behavior are triggered, ultimately promoting weight rebound. These responses may help explain why calorie-restricted diets frequently fail to produce lasting weight loss.

(1) Metabolic adaptation

Weight loss induced by calorie restriction leads to a significant reduction in resting energy expenditure beyond what would be predicted from changes in body composition. This metabolic adaptation occurs in both formerly obese individuals and naturally lean individuals who have lost weight, creating conditions that favor weight rebound.

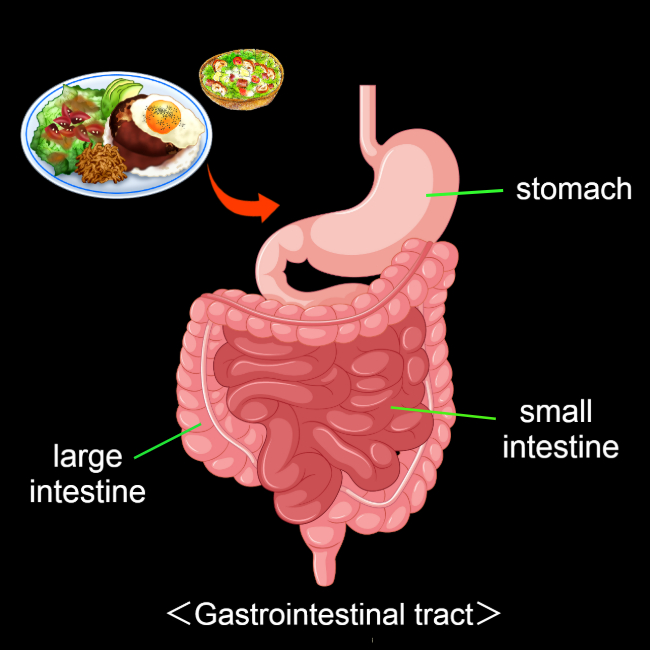

(2) Endocrine function

A wide range of hormones secreted from the gastrointestinal tract and adipose tissue—such as leptin, ghrelin, peptide YY, and cholecystokinin—play essential roles in regulating appetite, food intake, and energy expenditure. A calorie-restricted diet simultaneously decreases satiety and increases hunger, which can promote overeating.

(3) Food reward and addiction-like processes

When we eat palatable foods, neurotransmitters such as dopamine are released, activating reward-related neural circuits. The desire to experience this pleasure again motivates the next eating episode. Calorie restriction and fasting can heighten the reward value of food, especially energy-dense, highly palatable foods.

(4) Inhibitory system and binge eating

Short-term dieting success can be attributed to enhanced inhibitory neural responses that temporarily suppress the desire to eat. However, as dietary restrictions continue, activation of reward-related brain regions may begin to override inhibitory control, making it increasingly difficult to resist cravings for palatable foods.

(5) Adipose cellularity

Weight loss reduces the size of adipocytes (fat cells), but their number generally remains unchanged. However, some researchers have pointed out that the possibility of new fat cells forming (hyperplasia) during weight rebound cannot be completely ruled out. If hyperplasia does occur, these fat cells could enlarge again, potentially promoting further expansion of overall adipose tissue.

(6) Intestinal starvation

Unlike the situations described in (1)–(5), intestinal starvation does not arise from a marked deficiency in energy.

Conclusion

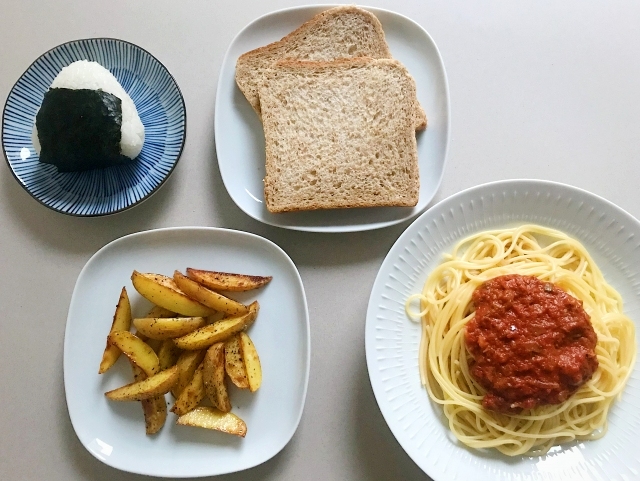

Some researchers argue that the biological forces driving weight rebound after weight loss are extremely powerful and difficult to overcome. In my opinion, rather than trying to fight these responses, it is more important to avoid triggering them strongly in the first place.

Specifically, instead of enduring prolonged hunger, it is helpful to consume more nutrient-dense, minimally processed foods while adjusting caloric intake. Doing so helps sustain satiety and reduce hunger—key factors in supporting long-term weight management.

【Full text】

-

Contents

- Various mechanisms that promote weight rebound

(1)Metabolic adaptation

(2) Endocrine Function

(3) Food Reward and Addiction-Like Processes

(4) Inhibitory system and binge eating

(5) Adipose cellularity

(6) Intestinal starvation - Conclusion

- Various mechanisms that promote weight rebound

<Introduction>

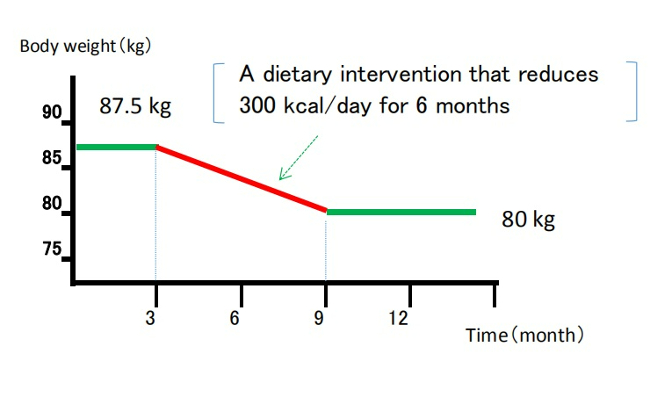

The prescription for people with obesity to ”eat less and exercise more”remains a widely used approach to weight management, despite its well-documented failures[1]. It has been suggested that most of the weight lost through dieting is regained over the long term[2].

According to research in genetics, epidemiology, and physiology, body fat and body weight are known to be tightly regulated. When a person attempts to maintain weight loss, adaptive responses involving coordinated changes in metabolic, neuroendocrine, autonomic, and behavioral functions are triggered, acting to oppose the maintenance of the reduced weight[4].

In this post, I’d like to take a brief look at these biological mechanisms that may drive weight rebound and even promote further weight gain after dieting. I will also explain how my theory of intestinal starvation differs from these mechanisms.

【Related Articles】 The Spread of Dieting May Be Fueling the Rise in Obesity

1.Various mechanisms that promote weight rebound

(1) Metabolic adaptation

Energy restriction is associated with a reduction in resting energy expenditure (REE)[5].

Many studies have reported that behavioral weight loss leads to a greater decrease in both resting and total energy expenditure than would be predicted based on changes in body composition and the thermic effects of food[4,6].

This phenomenon, known as adaptive thermogenesis (AT) or metabolic adaptation, creates conditions that favor regaining lost weight[7].

Metabolic adaptation can be interpreted teleologically as the body's survival response: when the body perceives a state of starvation, it reduces the energy costs of living in an attempt to prolong life. Interestingly, this response also appears to occur in individuals with obesity and does not seem to be diminished by the quantity of energy stored as body fat[7,8].

(Author: rawpixel.com / Source: Freepik)

However, regarding the timing of its onset, there is inconsistent evidence[9]. Some studies have detected adaptive thermogenesis (AT) within a week of energy restriction, which has been associated with rapid declines in insulin secretion, depletion of glycogen stores, and loss of intra-and extra cellular fluid[10].

In contrast, a growing body of evidence suggests that underfeeding-associated AT takes weeks to develop[11], primarily in association with reduced leptin secretion resulting from the reduction of stored fat[9,12].

Although the persistence of AT also remains a subject of debate[7], some studies indicate that this metabolic adaptation may continue for years even after energy balance has been reestablished at a lower weight[13].

(2) Endocrine function

A number of hormones secreted from the gastrointestinal tract and adipose tissue are known to play key roles in regulating appetite, food intake, energy expenditure, and body weight[14,15].

Leptin is a hormone secreted by fat cells that helps regulate body weight by suppressing appetite through stimulation of the satiety center and by increasing energy expenditure. High leptin levels are interpreted by the brain that energy reserves are high, whereas low leptin levels indicate that energy reserves are low[16].

It has been shown that leptin levels drop within 24 hours of energy restriction[17]. Interestingly, many studies have reported a greater reduction in leptin levels than would be expected for given losses of adipose tissue[18,19].

It has been suggested that the primary role of leptin may be the prevention of starvation, rather than weight regulation per se[15,20]. When leptin levels fall below a certain threshold—the point at which specific physiological responses are triggered(*1)—starvation defense mechanisms are activated, even if substantial fat stores remain[17]. This leads to a reduction in metabolic rate and physical activity, as well as an increase in hunger[21,22].

(* 1) It has been suggested that this threshold rises as fat mass increases[17].

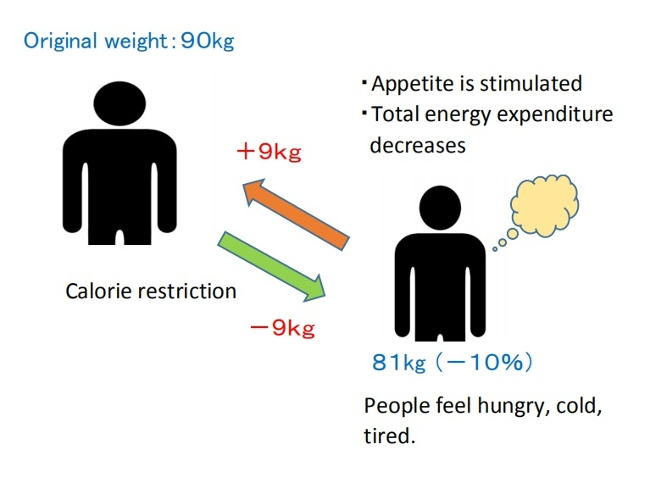

Furthermore, in individuals who have lost weight, an increase in the appetite-stimulating hormone ghrelin, along with decreases in the post-meal satiety signals peptide YY (PYY) and cholecystokinin (CCK), has been observed[23].

As a result, behavioral weight loss can simultaneously induce a decrease in satiety and an increase in hunger, potentially promoting overeating[15].

(3) Food reward and addiction-like processes

Food reward refers to the brain’s mechanism that generates pleasure and satisfaction from eating, as well as the motivation or desire to eat again. This process involves activation of the brain’s reward circuitry, where neurotransmitters such as dopamine are released, leading to feelings of well-being and increased appetite.

(Author: rawpixel.com / Source: Freepik)

The regulation of food intake is influenced by a close interaction between homeostatic and non-homeostatic (hedonic) factors.

The former is related to nutritional needs, monitoring available energy in the blood and fat stores to maintain energy balance. The latter, in contrast, is largely associated with the brain’s reward system[24,25].

Although the mechanisms that determine how much we eat are largely homeostatic, reward-related signals can easily override these normal satiety signals that help maintain a stable body weight, potentially leading to overeating[25,26].

Modern neuroimaging studies using fMRI have shown that both nutritional status (e.g., hunger vs. satiety) and different food stimuli (e.g., high vs. low calorie, appetizing vs. bland foods) can alter activity in the brain’s reward circuitry[27,28,29].

Recent studies in healthy individuals indicate that short-or long-term caloric restriction, as well as fasting, may increase the reward value of food—especially for high-calorie, palatable items[27,30].

These findings may help explain why calorie-restricted diets for weight loss often fail in the long term[28,30].

<Food Addiction and Its Differences from Drug Addiction>

While drugs and food share certain characteristics, they also differ in qualitative and quantitative ways.

Drugs of abuse, such as cocaine, act directly on the brain’s dopamine circuitry, whereas food influences the same circuits more indirectly. Signals from taste and smell, nutrient sensors in the digestive tract[31], and hormones released during digestion and absorption of ingested food all communicate with the brain and activate the dopamine system[25].

Although it remains debated whether specific food components such as sugar, sweeteners, salt, or fat can prompt addictive processes[25], highly palatable and calorie-dense foods—such as chocolate, ice cream, cookies, and salty snacks—can serve as powerful rewards.

In today’s stress-filled society, these foods provide pleasure and comfort, leading some researchers to draw parallels between “food addiction” and drug addiction[32,33].

(4) Inhibitory system and binge eating

Food intake is primarily regulated by three interactive neural systems: the homeostatic, reward-related, and inhibitory systems[15].

The inhibitory system—mainly involving the brain region responsible for self-control and decision-making—helps regulate eating behavior and inhibit excess food intake[34].

<Cognitive control of food reward>

In humans, the urge to seek and consume palatable foods can be moderated by cognition, specifically executive functions. One of the central dilemmas in daily life is balancing one’s internal goals (e.g., cutting back on sweets to maintain health and weight control) against the immediate reward of eating tempting foods. This conflict is particularly challenging when highly desirable foods, like donuts or pizza, are readily available[25].

(Source: Freepik)

The short-term success in dieting suggests that an increase in inhibitory neural responses can temporarily override the neurobiological drive to consume highly palatable high-calorie foods[35].

However, recent evidence indicates that reward-related neural signaling is activated in conjunction with inhibitory signaling[36].

In simple terms, as dietary restriction continues, it may become increasingly difficult to resist the urge to eat appetizing, high-reward foods.

Prospective studies in young individuals, as well as animal experiments in rodents, suggest that severe caloric restriction, characterized by 24-hour fasting or fat-free diets, may increase the risk of developing binge eating and bulimia in the future[37,38].

(5) Adipose cellularity

Weight loss dieting may reduce the size but not the number of fat cells[39]. It remains unclear whether hyperplasia (an increase in adipocyte number) contributes to weight rebound in weight-suppressed individuals[15]. However, in a study with obese rats, adipocyte hyperplasia has been observed following refeeding after fasting[40].

In humans, a similar possibility has been suggested[15].

Normally, when energy availability is low, triglycerides stored in fat tissue are broken down to supply energy to cells.

However, the rate of lipolysis (fat breakdown) appears to be related to adipocyte size and cellular surface area[41]—meaning that as fat cells shrink, their rate of lipolysis tends to decline.

If size-reduced adipocytes are functionally modified to break down less and store more fat, these cells may become enlarged, potentially promoting the overall expansion of adipose tissue[15,42].

(Author: brgfx / Source: Freepik)

(6) Intestinal starvation

The reactions described in section 1 to 5 are thought to represent a series of anti-starvation or anti-weight loss mechanisms(* 2) triggered by glycogen depletion or a significant decrease in stored body fat[15].

In contrast, intestinal starvation does not result from a depletion of energy. While it can occur under strict dietary restrictions aimed at weight loss—such as skipping meals or eating only very small portions—it may also be triggered by more casual dieting, or lifestyle habits not directly related to dieting, such as skipping breakfast, eating light lunches, having late dinners, or eating two meals a day.

【Related article】

Defining "Intestinal Starvation": Its Relevance to the Multifactorial Model of Obesity

I also believe that when intestinal starvation is induced, it leads to overall weight gain, suggesting an increase in body’s set-point weight. This increase likely involves not only body fat but also lean tissue such as muscle mass. Therefore, it may differ from weight gain mechanisms characterized by abnormal increases in abdominal and total body fat.

(* 2) Some researchers prefer the term "anti-weight loss" mechanism rather than anti-starvation, because these responses operate despite the presence of adequate energy stores[15].

2. Conclusion

Although a direct causal relationship between the five mechanisms (section 1-5) discussed here and weight rebound has not yet been proven[15], many people who have experienced rebounding after dieting may find these explanations relatable.

Some researchers point out that “the biological forces resisting weight loss and driving weight rebound are so powerful that most individuals attempting to lose weight through behavioral interventions are unlikely to overcome them.” At the same time, they emphasize the need to develop new strategies that can weaken these biological mechanisms in order to achieve long-term weight loss[15].

In my opinion, rather than trying to overcome these powerful biological forces, what’s truly important is to avoid triggering the anti-starvation (or anti-weight loss) mechanisms in the first place.

Currently, obesity is widely believed to result from excess caloric intake and/or lack of physical activity. Consequently, the common advice is to “eat less and exercise more.” However, many people try to reduce calories by eating light meals or very small portions (e.g., a simple sandwich, a simple burger) and endure extended periods of hunger. As the findings on food reward and inhibitory systems indicate, this approach clearly ignores the body’s natural biological mechanisms.

I would rather recommend the following approach:

• Mainly reduce refined carbohydrates and adjust total caloric intake—but avoid extreme restrictions.

• Increase other foods, such as fiber-rich vegetables, seaweed, dairy products, minimally processed meats and fish, and nuts. In particular, emphasize foods that are harder to digest or take longer to break down (* 2).

(* 2) Even high-calorie foods like oils and nuts can be appropriate depending on how they’re consumed.

By maintaining this dietary approach, the signal that "there is sufficient food available" may be transmitted through the gut-brain axis. Sustaining satiety and reducing hunger is key.

Moreover, nutrient-sensing systems in the digestive tract and other parts of the body have also been indicated to contribute to the generation of food reward during and after a meal[43]. By chewing slowly and savoring each bite, you can gain not only the immediate reward from taste buds but also a longer-lasting sense of satisfaction that extends well beyond the end of the meal[44].

The current obesity epidemic is often described as a mismatch between our modern, food-abundant environment and biological response patterns that evolved under food-scarce conditions[44,45].

From this perspective, I believe that in an environment where palatable food is readily available, even extended periods of hunger in daily life may actually promote long-term increases in body fat depending on how we combine foods.

<References>

[1] Bacon L, Aphramor L. Weight science: evaluating the evidence for a paradigm shift. Nutr J. 2011 Jan 24;10:9.

[2]National Institutes of Health Technology Assessment Conference Panel (1993) Methods for voluntary weight loss and control. Ann Intern Med 119, 764–770.

[3] Deleted

[4] Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL. Adaptive thermogenesis in humans. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010 Oct;34 Suppl 1(0 1):S47-55.

[5]Jiménez Jaime T et al. Effect of calorie restriction on energy expenditure in overweight and obese adult women. Nutr Hosp. 2015 Jun 1;31(6):2428-36.

[6]Johannsen DL et al. Metabolic slowing with massive weight loss despite preservation of fat-free mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Jul;97(7):2489-96.

[7]Hall KD, Guo J. Obesity Energetics: Body Weight Regulation and the Effects of Diet Composition. Gastroenterology. 2017 May;152(7):1718-1727.e3.

[8]Leibel RL, Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J. Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. N Engl J Med. 1995 Mar 9;332(10):621-8.

[9]Egan AM, Collins AL. Dynamic changes in energy expenditure in response to underfeeding: a review. Proc Nutr Soc. 2022 May;81(2):199-212.

[10]Heinitz S et al. Early adaptive thermogenesis is a determinant of weight loss after six weeks of caloric restriction in overweight subjects. Metabolism. 2020 Sep;110:154303.

[11] Dulloo AG, Seydoux J, Jacquet J. Adaptive thermogenesis and uncoupling proteins: a reappraisal of their roles in fat metabolism and energy balance. Physiol Behav. 2004 Dec 30;83(4):587-602.

[12]Müller MJ, Enderle J, Bosy-Westphal A. Changes in Energy Expenditure with Weight Gain and Weight Loss in Humans. Curr Obes Rep. 2016 Dec;5(4):413-423.

[13]Fothergill E et al. Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after "The Biggest Loser" competition. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016 Aug;24(8):1612-9.

[14]Schwartz MW et al. Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature. 2000 Apr 6;404(6778):661-71.

[15]Ochner CN et al. Biological mechanisms that promote weight regain following weight loss in obese humans. Physiol Behav. 2013 Aug 15;120:106-13.

[16]Hebebrand J et al. The role of hypoleptinemia in the psychological and behavioral adaptation to starvation: Implications for anorexia nervosa. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022 Oct;141:104807.

[17]Leibel RL. The role of leptin in the control of body weight. Nutr Rev. 2002 Oct;60(10 Pt 2):S15-9; discussion S68-84, 85-7.

[18]Löfgren P et al. Long-term prospective and controlled studies demonstrate adipose tissue hypercellularity and relative leptin deficiency in the postobese state. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Nov;90(11):6207-13.

[19]Rosenbaum M et al. Effects of weight change on plasma leptin concentrations and energy expenditure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997 Nov;82(11):3647-54.

[20]Ahima RS et al. Role of leptin in the neuroendocrine response to fasting. Nature. 1996 Jul 18;382(6588):250-2.

[21] Rosenbaum M et al. Energy intake in weight-reduced humans. Brain Res. 2010 Sep 2;1350:95-102.

[22]Kissileff HR et al. Leptin reverses declines in satiation in weight-reduced obese humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012 Feb;95(2):309-17.

[23] Sumithran P et al. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2011 Oct 27;365(17):1597-604.

[24]Chaptini L, Peikin S. Neuroendocrine regulation of food intake. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008 Mar;24(2):223-9.

[25]Alonso-Alonso M et al. Food reward system: current perspectives and future research needs. Nutr Rev. 2015 May;73(5):296-307.

[26]Begg DP, Woods SC. The endocrinology of food intake. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013 Oct;9(10):584-97.

[27]Goldstone AP et al. Fasting biases brain reward systems towards high-calorie foods. Eur J Neurosci. 2009 Oct;30(8):1625-35.

[28]Siep N et al. Hunger is the best spice: an fMRI study of the effects of attention, hunger and calorie content on food reward processing in the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex. Behav Brain Res. 2009 Mar 2;198(1):149-58.

[29]Haase L, Cerf-Ducastel B, Murphy C. Cortical activation in response to pure taste stimuli during the physiological states of hunger and satiety. Neuroimage. 2009 Feb 1;44(3):1008-21.

[30] Stice E, Burger K, Yokum S. Caloric deprivation increases responsivity of attention and reward brain regions to intake, anticipated intake, and images of palatable foods. Neuroimage. 2013 Feb 15;67:322-30.

[31] de Araujo IE et al. Food reward in the absence of taste receptor signaling. Neuron. 2008 Mar 27;57(6):930-41.

[32]Avena NM, Rada P, Hoebel BG. Sugar and fat bingeing have notable differences in addictive-like behavior. J Nutr. 2009 Mar;139(3):623-8.

[33]Berthoud HR, Zheng H, Shin AC. Food reward in the obese and after weight loss induced by calorie restriction and bariatric surgery. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012 Aug;1264(1):36-48.

[34]Pannacciulli N et al. Less activation of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in response to a meal: a feature of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 Oct;84(4):725-31.

[35]DelParigi A et al. Successful dieters have increased neural activity in cortical areas involved in the control of behavior. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007 Mar;31(3):440-8.

[36]Burger KS, Stice E. Relation of dietary restraint scores to activation of reward-related brain regions in response to food intake, anticipated intake, and food pictures. Neuroimage. 2011 Mar 1;55(1):233-9.

[37]Stice E, Davis K, Miller NP, Marti CN. Fasting increases risk for onset of binge eating and bulimic pathology: a 5-year prospective study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008 Nov;117(4):941-6.

[38]Ogawa R et al. Chronic food restriction and reduced dietary fat: risk factors for bouts of overeating. Physiol Behav. 2005 Nov 15;86(4):578-85.

[39]Gurr MI et al. Adipose tissue cellularity in man: the relationship between fat cell size and number, the mass and distribution of body fat and the history of weight gain and loss. Int J Obes. 1982;6(5):419-36. PMID: 7174187.

[40]Yang MU, Presta E, Björntorp P. Refeeding after fasting in rats: effects of duration of starvation and refeeding on food efficiency in diet-induced obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990 Jun;51(6):970-8.

[41]Arner P. Control of lipolysis and its relevance to development of obesity in man. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1988 Aug;4(5):507-15. PMID: 3061758.

[42]MacLean PS et al. Peripheral metabolic responses to prolonged weight reduction that promote rapid, efficient regain in obesity-prone rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006 Jun;290(6):R1577-88.

[43]Sclafani A, Ackroff K. The relationship between food reward and satiation revisited. Physiol Behav. 2004 Aug;82(1):89-95.

[44]Berthoud HR, Lenard NR, Shin AC. Food reward, hyperphagia, and obesity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011 Jun;300(6):R1266-77.

[45]Speakman JR. Thrifty genes for obesity, an attractive but flawed idea, and an alternative perspective: the 'drifty gene' hypothesis. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008 Nov;32(11):1611-7.

2024.10.14

The Increasingly Important "Set-Point" Theory of Body Weight: What are the Environmental and Behavioral Factors?

Summary

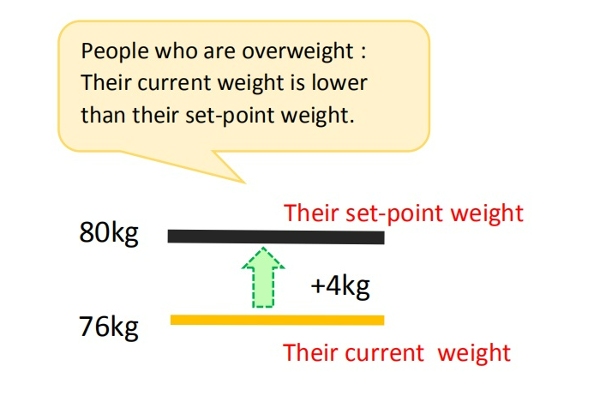

■In 1953, Kennedy proposed that body fat storage is regulated. In 1982, nutritionists William Bennett and Joel Gurin expanded on Kennedy’s idea and developed the set-point theory. This may help explain the recurring failure of long-term dieting.

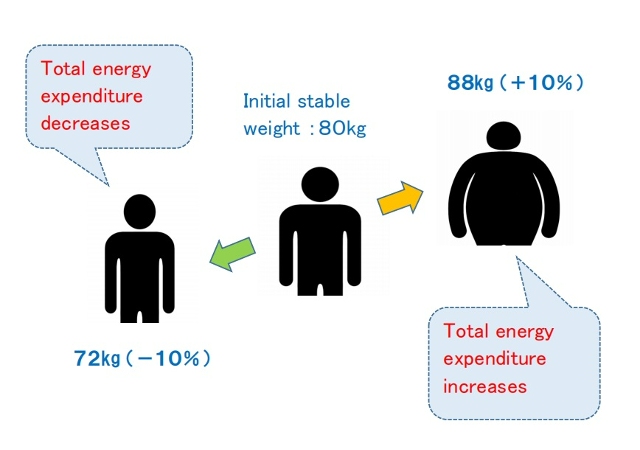

■When an individual loses weight, the body significantly reduces energy expenditure beyond what would be expected based on changes in body composition and the thermic effect of food. It also increases appetite through hormonal regulation, and alters food preferences to drive the body weight back toward a predetermined set-point range.

■Since obese individuals also exhibit these compensatory metabolic adjustments in response to dietary restriction, obesity may be considered a natural physiological state for some people.

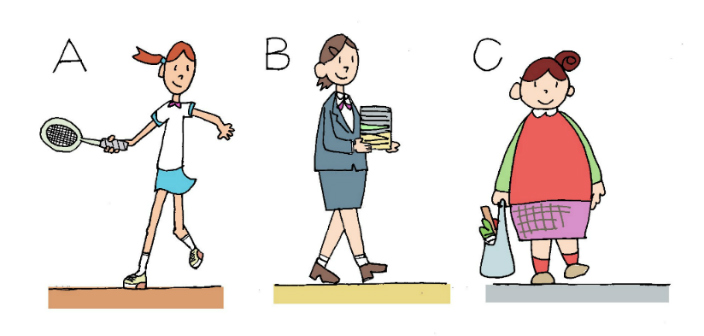

■This body’s set-point is thought to be established early in life and remains relatively stable unless altered by specific life changes, such as marriage, childbirth, menopause, aging, or illness.

■As demonstrated in overfeeding experiments conducted in Vermont in the 1960’s, even weight gain from temporary overeating can trigger compensatory mechanisms that bring body weight back toward its set-point range.

■However, this set-point model of body weight does not explain the global rise in obesity since around 1970. Some researchers point out that while metabolic resistance to sustaining a reduced body weight is strong, its resistance to sustained fat gain may weaken over time with prolonged consumption of high-calorie foods.

< My thoughts >

■As some researchers have suggested, whether obesity as a chronic disease can be cured is depend on understanding how genetic and environmental factors interact to adjust the body's set-point weight.

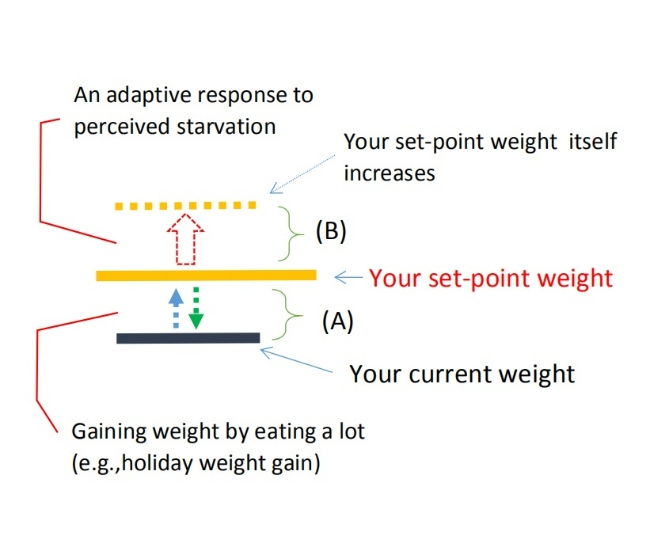

■Since it is generally believed that a positive energy balance is necessary for weight gain, some researchers suggest that today’s environment of continuous high-calorie food intake may result in irreversible weight gain, which also suggests an increase in set-point weight, but I have a different view.

■There are two types of weight gain. Weight gain from temporary overeating is due to a positive energy balance, but this is usually short-term, and body weight is likely to return to its set-point.

On the other hand, I believe that long-term, irreversible weight gain, which suggests an increase in set-point weight, is more likely triggered by a negative energy balance or internal signals of “food scarcity,” similar to cases where weight increases even more after periods of starvation or dieting.

■Since 1970, one notable change in our living environment is what I call “intestinal starvation.” In many parts of the world before 1970, even if people went a whole day without eating until the next meal, there were likely still fibers and other undigested substances left in the intestines.

However, in today’s society, where easily digestible foods—such as refined carbohydrates, certain kinds of protein, and [ultra-]processed foods—are widely consumed, intestinal starvation can be induced in as little as 8 to 10 hours depending on how one eats. Through the gut-brain axis, this may send a signal to the brain indicating "there is no food."

※For an explanation of why intestinal starvation may lead to irreversible weight gain—suggesting an increase in body's set-point weight—please see Section 4.

【 Full text 】

-

Contents

-

- Advances in understanding “set-point” theory

- Problems with the set-point model

- Environmental and behavioral factors influencing weight set-point

- Why intestinal starvation increases one’s set-point weight

<How to prove my theory>

- Advances in understanding “set-point” theory

As I've explained in previous blog posts, I believe that each person has an individual “set-point” for their weight, and that understanding how this set-point increases is the key to addressing the issue of obesity.

This time, I would like to share my thoughts on recent advances in research regarding the set-point theory of body weight, as well as the environmental and behavioral factors that influence it.

1. Advances in understanding “set-point” theory

<Obesity and weight loss attempts>

♦A fat person who insists that a lean friend has consistently eaten more than the fat person does, may well be telling the truth.(*snip*)

The group of obese patients who are greatly in need of our understanding are those who keep to a calorie intake of perhaps 1000 kcal per day, yet lose less than one kg per week. There is no doubt whatsoever that such people exist, and can be studied in a metabolic ward under conditions where 'cheating' is virtually impossible without being detected. Usually these are middle-aged women who have been perhaps 40 kg overweight, and who have already lost about 20 kg. They are often depressed, hypothermic, and have a low metabolic rate. The nature of this metabolic adaptation to a low calorie diet is not known (as of 1973), but it is a phenomenon which has been known since before 1920. [1](J S Garrow, 1973)

♦For obese individuals, a certain amount of weight loss is possible through a range of treatments, but long-term sustainability of lost weight is much more challenging, and in most cases, the weight is regained [2]. In a meta-analysis of 29 long-term weight loss studies, more than half of the lost weight was regained within two years, and by five years, more than 80% of lost weight was regained [3,4].

In addition, studies of those who are successful at sustained weight loss indicate that the maintenance of a reduced degree of body fatness will probably require close attention to energy intake and expenditure, perhaps for life[5].

<Metabolic values of obese individuals>

♦The hypometabolic thesis had fallen out of favor by 1930, when more accurate calculations of body-surface area indicated that the metabolic rates of obese individuals were normal[6].

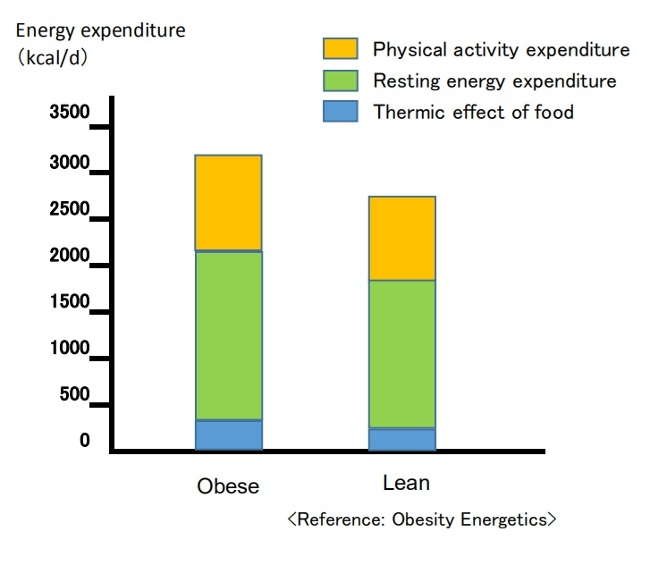

♦Total energy expenditure (TEE) in a day consists of three components: diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT), physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE), and resting energy expenditure (REE). When comparing a model case of men with an average weight of 100 kg and 70 kg, the man weighing 100 kg has a higher TEE[7] .

(Breakdown of energy expenditure in average 100-kg and 70-kg men)

Contrary to popular belief, people with obesity generally have a higher absolute REE compared to leaner subjects.This is because obesity increases both body fat and metabolically active fat-free mass[7,8].

PAEE can be subdivided into "voluntary exercise" and “activities of daily living.” Despite typically engaging in less physical activity, obese individuals often have a daily energy cost for physical activity similar to that of non-obese individuals since PAEE is proportional to body weight [7,9]. Additionally, due to a greater food intake, their DIT also tends to be higher [7].

<Dynamic changes in energy expenditure>

♦Obesity prevention is often erroneously described as a simple bookkeeping matter of balancing caloric intake and expenditure [10].

In this model, energy intake and expenditure are considered independent parameters determined solely by behavior. It is assumed that an obese person can steadily lose weight by eating less and/or moving more at a rate of one pound for every 3,500 kcal (or one kg for every 7,200 kcal) of accumulated dietary caloric deficit [7,11]. This view has been referred to as a “static model” of weight-loss, but it has been shown to be physiologically impossible [7,12].

(Static model of weight loss)

(Despite being recognized as overly simplistic, the 3,500 kcal rule continues to appear in scientific literature and has been cited in over 35,000 educational weight-loss websites as of 2013.) [12,13]

♦It is now understood that energy intake and expenditure are interdependent variables, influenced by each other and by homeostatic signals triggered by changes in body weight [7,14].

Attempts to alter energy balance through diet or exercise are countered by physiological adaptations that resist weight loss [7].

<Set-point theory of body weight>

♦In recent years, the influence of homeostatic control has been recognized, and there is growing evidence that the body employs physiological mechanisms to manipulate energy balance and maintain body weight at a genetically and environmentally determined "set-point."[12]

In 1953, Kennedy proposed that body fat storage is regulated [15]. In 1982, nutritional researchers William Bennett and Joel Gurin expanded on Kennedy's concept when they developed the set-point theory [16]. The model has been widely adopted, and strengthened particularly after the discovery of leptin in the 1990’s [7,12].

When an individual loses weight, the body significantly reduces energy expenditure to a degree that is often greater than predicted based on changes in body composition and the thermic effect of food. It also causes an increase in appetite through hormonal regulation and alters food preferences through behavioral changes, to drive the body weight back toward its set-point range[7,16].

( Set-point model of weight loss)

♦Weight-loss studies have shown that the magnitude of fat stores in the body is protected by mechanisms mediated by the central nervous system, which adjust energy intake (EI) and expenditure (EE) via signals from adipose tissue, the gastrointestinal tract, and endocrine tissue to maintain homeostasis, and resist weight change (set-point model)[12,17].

♦The body's protective metabolic mechanism that attempts to preserve energy stores during an energy crisis is known as adaptive thermogenesis (AT) or metabolic adaption[7,12].

AT is defined as the underfeeding-associated fall in resting energy expenditure (REE), independent of changes in body composition[12].

♦Maintenance of a 10% or greater reduction in body weight in lean or obese individuals is accompanied by about 20 to 25% decline in 24-hour energy expenditure. This reduction in weight maintenance calories is 10 to 15% lower than what is predicted based solely on alterations (/changes) in fat and lean mass [17,18].

Since obese individuals also display these compensatory metabolic adjustments in response to dietary restriction, obesity may be considered a natural physiological state for some people. Experimental studies on obesity in animals similarly suggest a view of obesity as a condition of body energy regulation at an elevated set-point [19].

♦A meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies investigating adaptive thermogenesis (AT) by comparing formerly obese subjects who had lost weight with BMI-matched subjects who were never obese, reported a 3–5 % lower resting energy expenditure (REE) in formerly obese subjects compared to never obese controls[20].

This effect means, for example, that if an obese woman reduced her weight from 100kg to 70kg, she would have to consume fewer calories to remain at 70kg than a woman who had consistently weighed 70kg[6]. Similar results have been confirmed in animal experiments involving obese and normal-weight rats.

This suggests that the frequent claim made by obese people that they eat the same or less than their lean friends but lose no weight, must be given more credence than it is ordinarily accorded[19].

♦On the other hand, as shown in overfeeding experiments on prisoners in Vermont in the 1960’s (Doctor Ethan Sims), weight gain due to temporary overeating also triggers compensatory mechanisms that bring body weight back into a set-point range.

However, some researchers point out that these may be weaker than those protecting weight loss. This asymmetry could be due to the evolutionary advantage of storing fat to survive during periods of caloric restriction, such as prolonged starvation [16,17].

♦In addition, hyperphagia (overeating) has been demonstrated following experimental semi-starvation and short-term underfeeding, which is probably the result of homeostatic signals resulting from the loss of both body fat and lean tissue [7,21].

♦This theory also suggests that a person's set-point for body weight is established early in life and remains relatively stable unless altered by specific conditions. However, the set-point may change throughout one’s life due to factors such as marriage, childbirth, menopause, aging, and disease [16].

On the other hand, the set-point theory remains a theory because all the molecular mechanisms involved in set-point regulation have not been elucidated, and some researchers may consider this theory to be overly simplistic[16].

2. Problems with the set-point model

However, some researchers have pointed out problems with the set-point model of regulation.

If such a powerful biological feedback system regulating the state of our body fat exists, then why do many individuals in most Western countries gain weight throughout majority of their lives? In particular, they argue that this model cannot explain the increasing prevalence of obesity that has been observed in many societies worldwide since the 1970’s[22].

In response, some researchers argue that while metabolic resistance to sustaining a reduced body weight is strong, metabolic resistance to sustained increased adiposity may not be physiologically long-lasting. The steadily increasing prevalence of obesity in humans also suggests that the state of body fat is facilitated more vigorously than losing weight[17,23].

Animal studies in mice demonstrated increased energy expenditure and increased sympathetic nervous system (SNS) tone during the first 3-4 weeks of consuming a high-fat diet, while these changes were no longer evident after a few months of high-fat diet consumption[17,24].

Another animal study in mice reported that long-term consumption of palatable, high-energy diets such as potato chips, cheese crackers, cookies, etc., caused irreversible weight gain, suggesting an increase in the set-point weight[19,25]. This effect is believed to be due to the increases in the number of fat cell[19,26].

■These explanations may sound reasonable at first, but in my opinion, this is no longer a "set-point" and it fails to explain why the body stubbornly shows metabolic resistance to maintaining weight loss, even at a higher set-point weight.

When applied to humans, not everyone who frequently consumes high-calorie foods becomes obese. This brings up several contradictions, such as:

(1)Why is obesity more prevalent among the lower-income groups in Western societies[22,27] and relatively wealthier groups in developing societies?[28];

(2)The coexistence of undernutrition and obesity in poor populations, observed globally since the 1950’s[29];

(3) Why do some people gain weight after environmental changes such as entering college, getting married, having children, or moving from Asia to Western countries?[22]

As I have mentioned repeatedly in this blog, I believe that an increase in set-point for body weight is due to inducing intestinal starvation, and that I can explain all these contradictions.

In the following section, I will explain that more specifically.

3. Environmental and behavioral factors influencing weight set-point

In 2012, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) designated obesity as a chronic disease. One of the rationale for that designation is that, like other chronic diseases, the pathophysiology of obesity is complex, involving interactions of genetic, biological, environmental, and behavioral factors[30].

Some researchers interested in the body weight set-point theory argue that understanding how genes and the environment interact to regulate the set-point is essential to determining whether obesity, as a chronic disease, can be cured. However, they struggle to explain the many significant environmental and social influences[22].

■ I also believe that the set-point of body weight changes due to the interaction between (1) genetic and biological factors, and (2) environmental and behavioral factors, but this time, I will mainly discuss (2) in this article.

When considering changes in living environment since the 1970’s, most researchers blame the rise in obesity on the increased availability of high-calorie foods and a decrease in physical activity as society became more affluent. In other words, they believe that a positive energy balance is necessary for weight gain.

However, paradoxically, the fact that the increasing prevalence of obesity coincides with an increase in weight-loss attempts[31] suggests that our understanding of energy balance may be flawed[12].

As suggested by overfeeding experiments, “temporary weight gain from overeating” and “irreversible weight gain occurring over many years ” are different. In my view, obesity as a chronic disease arises rather from signals of negative energy balance or "food scarcity" in the body, as in the cases where people gain more weight than before after starvation or dieting.

[Related article]

The Overfeeding Study Suggests That "Overeating" Is Not the Cause of Obesity

■Despite its impact on our bodies due to changes in our living environments since the 1970’s, "intestinal starvation" remains unrecognized.

Intestinal starvation refers to a state where everything consumed is fully digested throughout the entire intestinal tract, and it can occur in today's affluent developed countries, developing countries, or even among the poor. When there is little or no fiber and everything has been digested, our bodies perceive it as having "no food."

【Related Article】

The Body Perceive That It Is More Starved than in the Past

Perhaps in many parts of the world before 1970, even if people went a whole day without eating until their next meal, there were likely still undigested substances like fiber and tough plant cell walls left in their intestines. However, in today’s society, with its abundance of easily digestible, refined carbohydrates, processed foods, and fast food, intestinal starvation can occur in as little as eight to ten hours, depending on eating habits.

Intestinal starvation is more likely to occur with frequent consumption of easily digestible refined carbohydrates (bread, noodles, rice, etc.), industrially processed meat or fish products, fast food, and snacks, etc., combined with a lack of vegetables and long periods of prolonged hunger (such as skipping breakfast, late-night meals, or irregular eating habits).

【Related Article】

■In the animal experiments on rats described in section 2 above, it was reported that consuming a "high-energy diet" for 90 days led to irreversible weight gain, suggesting an increase in the set-point. However, the "fattening” diet used in this experiment (Rolls et al., 1980) primarily consisted of highly palatable items like potato chips, cheese crackers, and cookies sold in supermarkets. Those foods contained 47.5% industrially processed refined carbohydrates (fat: 42%, protein: 10.5%) on an energy basis[25]. Moreover, rats only eat when they’re hungry, and they are capable of eating the same food repeatedly.

In contrast, the “chow” fed to the control rats may have been made from ingredients like ground wheat, ground corn, soybean meal, and fish meal, etc. In other words, just as our diets from over fifty years ago, it likely contained a high amount of indigestible components, such as fiber and tough plant cell walls.

Therefore, I question the conclusion that highly palatable "high-energy diets" alone caused the irreversible weight gain.

4. Why intestinal starvation increases one’s set-point weight

Below, I will explain the mechanism by which the set- point for body weight increases due to the induction of intestinal starvation. While some of it involves speculation, it is based on events that have happened to me several times. You may not believe it, but at least for me, it is 100% accurate.

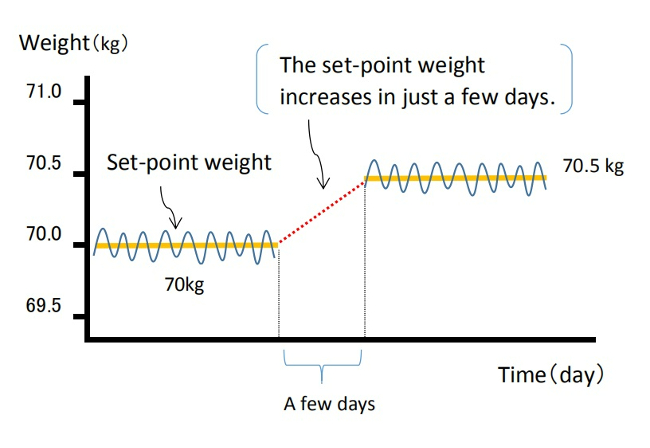

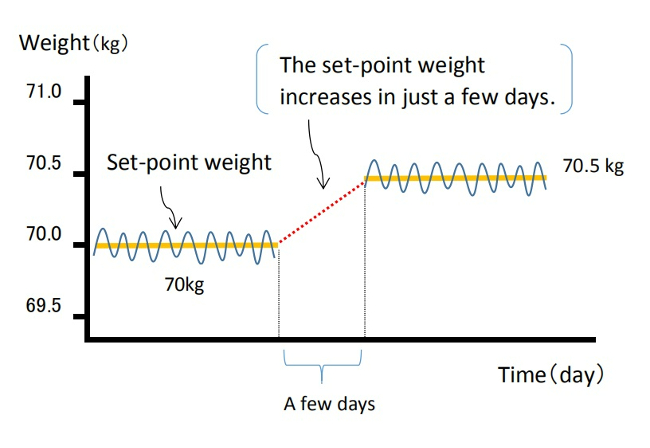

■Let's assume there is a man who has maintained a weight of 70 kg for many years. Even though his weight may fluctuate slightly during busy periods or after overeating, his weight revolves around 70 kg, so his set-point would be considered 70 kg.

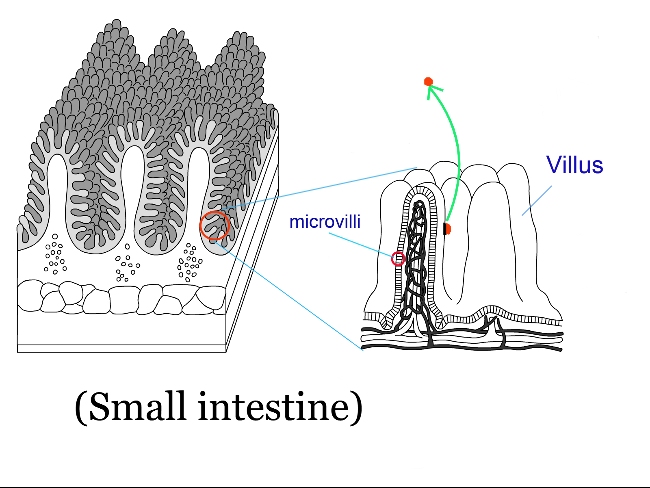

When intestinal starvation occurs, a signal that 'there is no food' is transmitted from the intestines (or small intestine) to the brain.

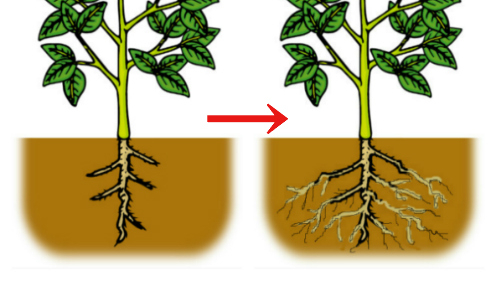

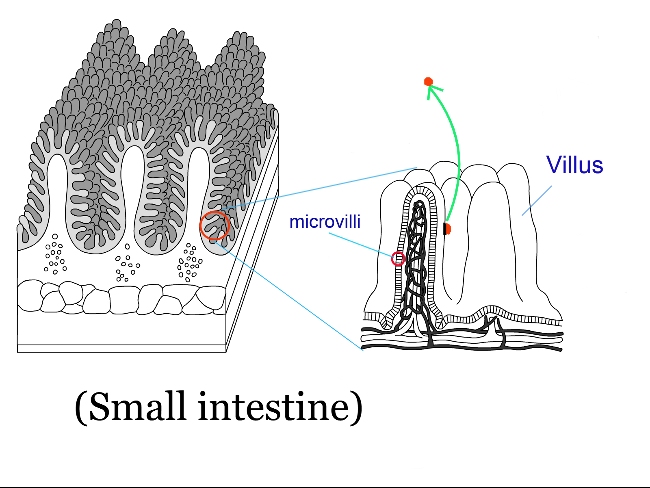

As a result, the body tries to absorb more nutrients, causing microscopic substances attached to the villi (or microvilli) in the small intestine to detach (Figure 1), thereby increasing the surface area for absorption and raising the absolute absorption ability.

In other words, I believe that weight gain, at least to some extent, involves not only an increase in body fat but also lean tissue such as muscle.

(Fig. 1 )

(Normally, a few undigested fiber or fats may remain, but when all food is perfectly digested, 5 to 10 kg of weight gain over a short period is possible.)

As a result, I believe the weight balancing point (the set-point) increases and reaches equilibrium within just a few days (Figure 2).

Weight gain does not occur from the gradual accumulation of excess calories each day, but rather in one sudden jump, possibly 0.3kg or 0.5g.

When dieting, the set-point can unknowingly rise, so you may gain a few pounds more than before once the diet ends.

(Fig. 2 )

Once the body’s balance point rises, it becomes harder to lose weight because the overall absorption ability has increased. As mentioned in reference in section 1 , I agree with the idea that obesity is a “state of energy regulation at a higher set-point,” and is "a natural physiological condition" for obese individuals.

For more details, please refer to the article below.

【Related Article】

Gaining Weight by Intestinal Starvation; What Does It Mean?

<How to prove my theory>

It may be difficult to determine the exact cause when someone gains a few kg in a year, meaning their highest weight ever. However, I believe that, even with reduced calorie and carbohydrate intake from the meals I provide, it is possible to significantly increase a person's weight (by around 5 to 10 kg) within a few months, setting a new high set-point weight. By observing the data before and after, I think it is possible to investigate what changes have occurred inside the body.

<References>

[1]Garrow JS. Diet and obesity. Proc R Soc Med. 1973 Jul;66(7):642-4. PMID: 4741395; PMCID: PMC1645095.

[2]Wu T, Gao X, Chen M, van Dam RM. Long-term effectiveness of diet-plus-exercise interventions vs. diet-only interventions for weight loss: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2009;10(3):313–323.

[3] Hall KD, Kahan S. Maintenance of Lost Weight and Long-Term Management of Obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2018 Jan;102(1):183-197.

[4]Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, Wood CL. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001 Nov;74(5):579-84.

[5]Wing RR, Hill JO. Successful weight loss maintenance. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:323-41.

[6]Jou C. The biology and genetics of obesity--a century of inquiries. N Engl J Med. 2014 May 15;370(20):1874-7.

[7]Hall KD, Guo J. Obesity Energetics: Body Weight Regulation and the Effects of Diet Composition. Gastroenterology. 2017 May;152(7):1718-1727.e3.

[8]Nelson KM, Weinsier RL, Long CL, et al. Prediction of resting energy expenditure from fat-free mass and fat mass. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56:848–856.

[9]Westerterp KR. Physical activity, food intake, and body weight regulation: insights from doubly labeled water studies. Nutr Rev. 2010;68:148–154.

[10] Levine DI. The curious history of the calorie in U.S. policy: a tradition of unfulfilled promises. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52:125–129.

[11] Hall KD, Chow CC. Why is the 3500 kcal per pound weight loss rule wrong? Int J Obes (Lond). 2013 Dec;37(12):1614.

[12] Egan AM, Collins AL. Dynamic changes in energy expenditure in response to underfeeding: a review. Proc Nutr Soc. 2022 May;81(2):199-212. doi: 10.1017/S0029665121003669. Epub 2021 Oct 4. PMID: 35103583.

[13]Thomas DM, Martin CK, Lettieri S et al. (2013) Can a weight loss of one pound a week be achieved with a 3500-kcal deficit? Commentary on a commonly accepted rule. In Int J Obes 37, 1611–1613.)

[14]Hall KD, Heymsfield SB, Kemnitz JW et al. Energy balance and its components: implications for body weight regulation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012 Apr;95(4):989-94.

[15]KENNEDY GC. The role of depot fat in the hypothalamic control of food intake in the rat. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1953 Jan 15;140(901):578-96.

[16] Ganipisetti VM, Bollimunta P. Obesity and Set-Point Theory. 2023 Apr 25. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 37276312.

[17] Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL. Adaptive thermogenesis in humans. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010 Oct;34 Suppl 1(0 1):S47-55.

[18] Leibel R, Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J. Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. N Eng J Med. 1995;332:621–28.

[19] Richard E. Keesey, Matt D. Hirvonen, Body Weight Set-Points: Determination and Adjustment, The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 127, Issue 9, 1997, Pages 1875S-1883S, ISSN 0022-3166.

[20]Astrup A, Gøtzsche PC, van de Werken K, et al. Meta-analysis of resting metabolic rate in formerly obese subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999 Jun;69(6):1117-22.

[21] Dulloo AG, Jacquet J, Girardier L. Poststarvation hyperphagia and body fat overshooting in humans: a role for feedback signals from lean and fat tissues. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:717–723.

[22]Speakman JR, Levitsky DA, Allison DB, et al. Set points, settling points and some alternative models: theoretical options to understand how genes and environments combine to regulate body adiposity. Dis Model Mech. 2011 Nov;4(6):733-45.

[23] Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Seeley RJ, et al. Is the energy homeostasis system inherently biased toward weight gain? Diabetes. 2003 Feb;52(2):232-8.

[24] Corbett SW, Stern JS, Keesey RE. Energy expenditure in rats with diet-induced obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1986 Aug;44(2):173-80.

[25] Rolls B.J., Rowe E.A., Turner R.C. Persistent obesity in rats following a period of consumption of a mixed high energy diet. J Physiol. 1980 Jan;298:415-27.

[26]Faust I.M., Johnson P.R., Stern J.S., Hirsch J. Diet-induced adipocyte number increase in adult rats: a new model of obesity. Am. J. Physiol., 235 (1978), pp. E279-E286

[27] Dykes J et al. Socioeconomic gradient in body size and obesity among women: the role of dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger in the Whitehall II study. International Journal of Obesity 2004 Feb,:262-68.

[28] Poskitt EM. Countries in transition: underweight to obesity non-stop? Ann Trop Paediatr. 2009 Mar;29(1):1-11.

[29] Gary Taubes. 2011. Why we get fat. New York: Anchor Books, Pages 31-40.

[30]Garvey WT. Is Obesity or Adiposity-Based Chronic Disease Curable: The Set Point Theory, the Environment, and Second-Generation Medications. Endocr Pract. 2022 Feb;28(2):214-222.

[31]Montani JP, Schutz Y, Dulloo AG. Dieting and weight cycling as risk factors for cardiometabolic diseases: who is really at risk? Obes Rev. 2015 Feb;16 Suppl 1:7-18.

2024.06.20

The Overfeeding Experiment Suggests That "Overeating" Is Not the Cause of Obesity

Contents

- Can overfeeding experiments make people obese?

- Subsequent overfeeding experiments

- Can metabolism explain this weight regain?

- Difference between obesity and overfeeding experiments: My thoughts

1. Can overfeeding experiments make people obese?

According to George A. Bray (as of 2020, an emeritus professor at Pennington Biomedical Research Center), until the 1960’s, obesity was viewed as a "lack of will power," and many people thought, and some said "if only these patients would push themselves away from the table, they would not have this problem."

With this view of obesity, he reflects that the turning point for obesity being accepted as a bona fide area of academic interest were the studies on overfeeding. Overfeeding studies began to provide valuable insights into the biology of obesity. For Doctor Bray, who was a postdoctoral fellow at the New England Medical Center Hospital in Boston at the time, the excitement that was generated when the Vermont overfeeding studies were first presented in 1968 was unforgettable[1].

This was the case with the overfeeding experiments conducted by Doctor Ethan Sims in the late 1960’s. Until then, it was commonly believed that, "overeating obviously leads to obesity," so few such experiments had been conducted.

According to Dr. Jason Fung, the author of “The Obesity Code,” Dr. Sims recruited lean students at the nearby University of Vermont and encouraged them to eat a lot to gain weight. However, despite what both he and the students had expected, the students did not become obese.

Suspecting that the students might have been increasing their exercise, Dr. Sims changed course. He then recruited convicts at the Vermont State Prison as subjects. Physical activity was strictly controlled, and attendants were present at every meal to ensure the calories-4000 per day-were eaten.

Although the prisoners’ weight initially rose, it then stabilized. While some prisoners gained more than twenty percent of their original body weight, the extent of weight gain varied significantly among them[2] .

Over two hundred days on this overfeeding regimen, twenty inmates gained an average of twenty to twenty-five pounds. (About 10 kg.) However, once the experiment ended and their caloric intake returned to normal, the men had difficulty maintaining the weight gain, and most shed all the weight they had gained relatively easily. The exceptions were two inmates who struggled to lose that weight[3].

At the time, Dr. Bray was allowed to participate as a co-researcher in Dr. Sims' experiment to examine the metabolic changes occurring in adipose tissue during the weight gain that followed overfeeding.

Later, in 1972, he conducted his own overeating experiment, using himself as a guinea pig. Initially, he tried to double what he usually ate at each meal, but he couldn't finish, so he switched to energy-dense foods, such as ice cream.

Over the next ten weeks, he gradually gained ten kilograms, and repeated his tests such as measuring the thermic effect of foods.

But once he stopped stuffing himself, his weight rapidly decreased, returning to his original seventy-five kilograms six weeks later, and he has maintained this weight with no trouble ever since.

Following his self-experiment, the other four volunteers in this study began overeating in the summer of 1972. When the experiment ended, all the volunteers returned to their baseline weight.

Dr.Bray states that this rapid return to normal weight contrasts with the difficulties people with spontaneous obesity have in losing weight, and the even more difficult task of a maintaining a lower weight. Many who develop obesity over years suffer from a different kind of pain than those of us who acutely gain weight by overfeeding. For them, the obesity “slips up” on them and once present, is difficult to reverse.

The history of overfeeding and underfeeding trials and other lines of evidence clearly show that obesity prevention and treatment cannot simply rely on the advice to "eat less and exercise more." [1]

2. Subsequent overfeeding experiments

Alex Leaf (Western States University) and Jose Antonio (Nova Southeastern University) reviewed overfeeding studies conducted up to 2017 that evaluated various combinations of macronutrient overfeeding and its effects on body composition.

They found twenty-five overfeeding studies that reported changes in fat mass (FM) and fat-free mass (FFM), in addition to changes in body weight. The study durations ranged from nine to one hundred days, and all but four were conducted in sedentary populations[4]. Notably, the objectives of each study varied, and not all mentioned weight loss following the end of the experiments.

To give a few examples, a study on identical twins was published in 1990.

■Bouchard (Laval University, Canada) et. al. recruited twelve pairs of young adult male identical twins (twenty-four individuals) with no exercise habits. Each participant's energy requirements were measured during a two-week base-line period, and after that, they were overfed by 1000 kcal per day (comprising 15% protein, 35% fat, and 50% carbohydrates), six days per week, for a total of eighty-four days during a one hundred-day period. The men were housed in a closed section of a university dormitory, and were under supervision by staff all day.

The mean weight gain was 8.1 kg, of which 67% was fat mass (FM). However, the weight gain varied widely among participants, ranging from 4.3 to 13.3 kg[5].

Four months after the experiment ended, the twins' average weight was 61.7 kg, which was only 1.3 kg higher than their baseline weight of 60.4 kg, indicating they had almost returned to their original weight[1].

■Conford (University of Michigan) et. al. conducted a study in 2012 involving nine healthy, non-obese adults (seven men and two women). The participants were admitted to the hospital for two weeks, during which time they ate 4000 kcals per day (comprising 15% protein, 35% fat, and 50% carbohydrates). Their energy requirements were determined during a one-week baseline period before the start of the experiment. In addition to three main meals, they had four snacks each day. The average weight gain was 2.1 kg, of which 67 % was fat mass (FM).[6]

The summary of this review indicates that overfeeding healthy, sedentary adults with a diet moderately high in both carbohydrates and fats (35-50% energy intake each) and low in protein (11-15%) primarily results in a gain in fat mass (FM), which accounts for 60-70 % of the weight gain. Additionally, the increase in fat-free mass (FFM) may be due to an increase in body water content rather than skeletal muscle tissue. In contrast, diets with significantly increased protein intake showed favorable changes in body composition, even with increased energy intake[4].

3. Can metabolism explain this weight regain?

Why did the participant’s weight rapidly return to normal over the ensuing weeks when they stopped overeating?

According to Dr. Bray, one of the striking findings in this Vermont study was that to maintain the weight they gained after overfeeding, they required more energy per unit surface area than before weight gain. When Dr. Bray moved to the University of California in 1970, his new lab began operating to explore his hypothesis about why extra energy was required to maintain the increased weight[1].

■Leibel (Rockefeller University) et. al. conducted a study in 1995 involving eighteen obese (BMI of 28 or higher) subjects (Group A) and twenty-three subjects who had never been obese (Group B).

They measured changes in energy expenditure under three conditions: at their usual body weight, after losing more than 10 percent of their body weight by underfeeding, and after gaining 10 percent of their body weight by overfeeding.

When maintaining a body weight at a level 10% or more below their initial weight, the total energy expenditure decreased by 8±5 kcal per kilogram per day in Group A and by 6±3 kcal in Group B.

Conversely, when maintaining a body weight at a level 10% above their initial weight, total energy expenditure increased by 8±4 kcal in Group A and by 9±7 kcal in Group B.

The study concluded that maintenance of a reduced weight or elevated body weight is associated with compensatory changes in energy expenditure, which resist maintaining the altered body weight and function to restore the original weight. This suggests that the long-term effectiveness of obesity treatment through caloric reduction may be limited[7].

4. Difference between obesity and overfeeding experiments: My thoughts

As Dr. Bray mentioned, I also believe that weight gain from temporary excessive caloric intake is due to body mechanisms entirely different from those underlying fundamental obesity. If compensatory metabolic mechanisms resist changes in body weight, why do some people continue to gain weight?

As I have repeatedly mentioned through this blog, the difference between people who are overweight and lean can be explained by the difference in set-point for body weight. (One's set-point weight goes up through intestinal starvation.)

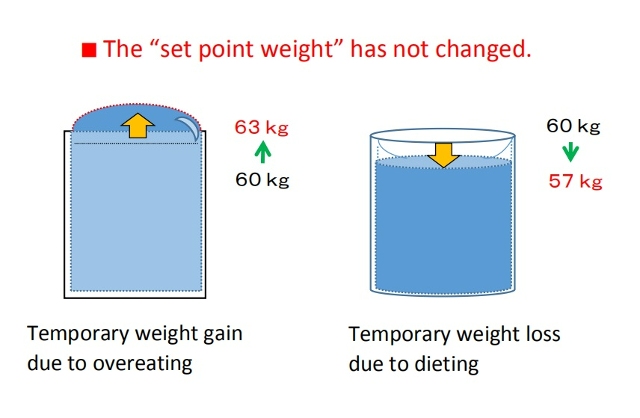

For example, suppose a person who normally weighs a stable sixty kg is temporarily overfed and reaches sixty-three kg.

This can be compared to a glass of water that is usually filled to about 97% now being filled to 100%, and then surface tension causing the water to rise above the rim.

Conversely, maintaining a weight of fifty-six kg by eating less is like the water level temporarily decreasing, causing a dip in the surface of the water.

In both cases, the set-point weight has not changed.

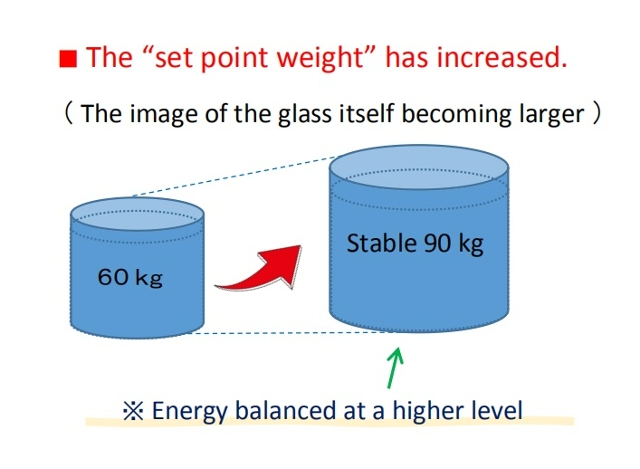

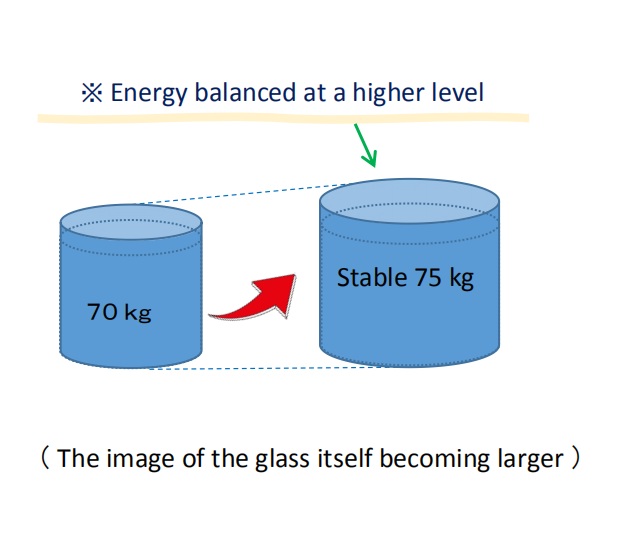

In contrast, if a person who originally weighs sixty kg gradually gains weight over several years, and then maintains a stable weight of ninety kg, this indicates that the set-point weight itself has increased, meaning the glass has grown larger, with energy balancing at a higher level.

Today, we are sometimes said to be living in an "obesogenic environment" that promotes obesity, but that does not necessarily mean consuming high-calorie foods or living sedentary lifestyles. As some researchers have already mentioned, calorie counting is clearly of little significance. Changes in caloric intake only lead to temporary weight gain or loss.

Rader, the "obesogenic environment" in my opinion is related to foods that are overly digestible foods (refined carbohydrates, fast food, processed foods, etc.) and an imbalanced diet (lack of vegetables, etc.). When these factors overlap with some other conditions such as skipping breakfast or eating late dinners, intestinal starvation is more likely to be induced.

Of course, researchers will say that in order to gain weight, more energy must be taken into the body than before. For more on why intestinal starvation leads to greater energy intake and weight gain, please refer to the article below.

[Related article] Gaining Weight by Intestinal Starvation; What Does It Mean?

<References>

[1]Bray GA. The pain of weight gain: self-experimentation with overfeeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020 Jan 1;111(1):17-20.

[2] Fung J, The Obesity Code, Greystone books, 2016, P114-116.

[3] Jou C. The biology and genetics of obesity--a century of inquiries. N Engl J Med. 2014 May 15;370(20):1874-7.

[4] Leaf A, Antonio J. The Effects of Overfeeding on Body Composition: The Role of Macronutrient Composition. Int J Exerc Sci. 2017 Dec 1;10(8):1275-1296.

[5] Bouchard C et al. The response to long-term overfeeding in identical twins. N Engl J Med. 1990 May 24;322(21):1477-82.

[6] Cornford AS et al. Rapid development of systemic insulin resistance with overeating is not accompanied by robust changes in skeletal muscle glucose and lipid metabolism. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013 May;38(5):512-9.

[7] Leibel RL et al. Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. N Engl J Med. 1995 Mar 9;332(10):621-8.

2019.08.14

Gaining Weight by Intestinal Starvation; What Does It Mean?

Contents

- Hunger in Africa and hunger in the modern era

- Why do we gain weight during periods of starvation?

- What happens when one’s set-point weight is elevated?

Let me explain something about the core of this blog.

Perhaps for most of you it is hard to believe me, but I’ll just write the facts as they are, as I experienced them. I did not write this from my imagination, but based it on my own analysis of what actually happened to me.

When I got into college, my total body weight fell down to the thirty-kilo range, so I knew exactly why I gained almost five kilos so rapidly in a few days, even though I didn’t eat much.

1. Hunger in Africa and hunger in the modern era

The idea of storing fat in the body as a reserve against starvation is something every researcher considers at one time or another.

However, it is said that this theory is an idea that has been rejected by researchers throughout history. This is because many overweight people often eat more, and many African refugees are thin and malnourished.

One might say, “If starvation makes us fat, then African refugees would be obese.”

However, please understand that this is a true state of starvation (malnutrition) in which the people can’t eat even if they want to, and I’m stating that it is different from what I call “intestinal starvation.”

African refugees do not have access to digestible food, and malnutrition even diminishes their ability to digest food and nutrients.

In contrast, many of us in developed countries are more likely to eat westernized foods made from wheat, meat, eggs, etc., which provide good nutrition and are easier to digest. Therefore, if we focus on the inner workings of our intestines, we are more prone to inducing intestinal starvation.

The reality is that being overweight has become a problem even among the poor populations in the world. What is common in these cases is not the excessive intake of calories or sugars, but rather a diet that is low in nutritional value and unbalanced, often due to a reliance on inexpensive refined carbohydrates and a lack of vegetables.

2. Why do we gain weight during periods of starvation?

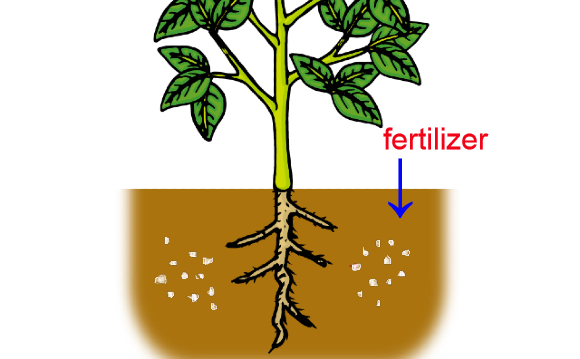

In my blog, I mentioned that one’s set-point for body weight goes up by inducing intestinal starvation, and I want to explain what it means here. For the sake of explanation, I will use plants as an example.

(1) For plants, eating food and gaining weight is done by adding "fertilizer." This fertilizer is the equivalent to our diet, and of course, we need to use fertilizer periodically for growth.

However, using too much fertilizer doesn’t usually result in producing a bigger plant, and if we use it too often, it may sometimes have a negative effect.

The same goes for humans, and just eating a lot of calories doesn’t necessarily mean we all gain weight and become overweight. Even if we eat only one meal a day, as long as it’s well-balanced, there will be enough nutrition left in the intestines to be absorbed.

(2)Using an example of a plant, weight gain by inducing intestinal starvation and an increase in set-point for body weight could be explained in the same way as a plant that is extending its roots and taking in more nutrients. (See figure below)

When there is not enough nutrition, plants grow their roots deeper into the ground seeking more nutrients, and the same phenomenon occurs when we humans digest all the food in our entire intestines (or it may be the small intestine only), and intestinal starvation is induced.

(It is said that “the small intestine is the second brain” or that “it has a will,” and I clearly felt the will of my small intestine.)

Actually the villi (*1) of the intestines do not grow, but I believe that the following phenomena occur:

(*1)In order to absorb more nutrients efficiently, the interior of the small intestine has a folded structure, with numerous protrusions called villi on its surface (Fig. 1). Additionally, microvilli develop on the surface of these villi.

It is sometimes said that if all of these were spread out, the surface area inside the small intestine would be equivalent to that of a tennis court.

<Fig. 1> Villi of the small intestine

First, I believe that the intestines (especially the small intestine) is the first organ to sense whether or not food is present. This is determined not only by the amount of energy, but also by how far the food has been digested. (For this reason, even if you eat a large amount, if your diet is heavily skewed towards easily digestible carbohydrates, intestinal starvation can be induced.)

When undigested substances, including fiber, remain in the intestines to some extent, the body perceives that “there is still food,” even if you're hungry. However, when all the food is digested (or very close to it), the small intestine sends a signal to the brain that “there is no food.”

In response, the body attempts to absorb more nutrients, and microscopic substances attached to the villi (or microvilli) of the small intestine detach themselves (Fig. 2). This, in turn, increases the surface area for absorption, thereby boosting absolute absorption capacity.

This causes weight gain, suggesting an increase in the set-point for body weight, and reaches a new equilibrium at a higher set-point within just three to four days.

<Fig. 2 >

In other words, weight doesn't gradually increase due to excess calories being stored bit by bit. Instead, the body normally maintains a stable set-point weight, but at some point, it suddenly jumps, whether by 300 grams or 500 grams, all at once (Fig. 3).

In summary, I believe that one of the key factors in the fundamental difference between obese and lean people involves their absorption ability.

[Related Article]

< Fig. 3 >

In Japan, obese individuals sometimes say things like, “I gain weight even just by drinking water.”

Of course, water alone does not make them fat, but I don't think it is totally wrong. It reflects just how efficient their absorption rate is.

3. What happens when one’s set-point weight is elevated?

(1) Once you gain weight, it becomes more difficult to lose weight

When your set-point for body weight goes up and you gain weight, it means that the balancing point, in terms of "energy- in, energy-out," has gone up, which can generate a more positive energy cycle and make it more difficult to lose weight.

When dieting, temporarily reducing the caloric intake to lose weight means reducing the "fertilizer" in the example of a plant. However, it is only a temporary weight loss, and you will likely return to your original weight when you start eating a normal diet again (the rebound effect).

Moreover, the reason why each time some people diet, they rebound and gain more weight than before is that skipping meals or eating light meals (not enough vegetables) can lead to intestinal starvation, which can further increase your set-point weight.

(2) More muscle, too

It is not that after you get fat, you gain muscle to support it. Since the overall absorption of nutrients increases, I believe that weight gain, at least to some extent, involves not only an increase in body fat but also lean mass such as muscle.

When a fat person loses body fat, they often have a thick, muscular chest or thighs. After body fat is gained, would the muscles around the chest and neck thicken to support that weight? (This varies widely from person to person.)

(3) Cause-and-effect reverse phenomenon

The increased intake of nutrients as a whole, including protein, creates a positive cycle of energy, which leads to the following phenomena.

Since digestive enzymes, hormones, etc. are also made from proteins (amino acids), it could enhance the ability to digest food and potentially bring about changes in the hormonal systems that regulate appetite and other functions. So, it is no wonder that people with larger bodies or stronger stomachs generally eat more than others.

There exists a cause-and-effect reversal phenomenon: people do not gain weight because they eat more, but because the bigger they are, the hungrier they become, and in turn, they eat more.

(4) Those who are overweight are prone to gaining more weight

Even if everyone eats exactly the same amount, people with big bodies-big, meaning large with some extra body fat or muscularly built-, or obese people, are more likely to feel hungry, which means that they eat relatively less, and they tend to gain more weight little by little.

It may be a vicious circle where a person eats modest amounts and gains weight, and if they skip meals or eat less to lose weight, they gain even more weight in the long run.

【Related article】→What Does It Mean to Eat Relatively Less?

On the other hand, if a lean person eats balanced meals three times a day, every day, he or she doesn’t induce intestinal starvation. And there is a good chance they will stay the same weight and have the same appearance for the rest of their life, regardless of caloric intake.

Therefore, "fatness" and "non-fatness," in this regard, are not due to obesity genes.

Also, for people like me who are very thin, being thin itself can reduce the amount of protein and other nutrients that can be taken in, thus a negative energy cycle continues. In turn, the muscles that support the stomach and intestines become weak and droopy, and the ability to digest food is also diminished by not secreting enough digestive enzymes.

This is a vicious circle where thin people can’t gain weight and remain thin.

2016.10.17

Three (+1) Factors That Accelerate “Intestinal Starvation”

-

Contents

-

- Unbalanced diets and irregular lifestyles make intestinal starvation more likely

- This last, but not least important factor, what is “+1”?

1. Unbalanced diets and irregular lifestyles make intestinal starvation more likely

This time, I would like to discuss three key factors-plus one additional factor-that may contribute to the occurrence of what I call “intestinal starvation."

【Related article】

In Japan, the following are often cited to be associated with weight gain other than caloric intake:

(a) An unbalanced diet

• Fast food and junk food

• Excess intake of sugar and carbohydrates

• Lack of vegetables

(b)An irregular lifestyle

• Eating dinner late at night

• Skipping breakfast or lunch

• The frequency and type of snacking

In addition to these, many other factors may also be indirectly involved in the recent increase in obesity. However, it is not always clear how multiple factors combine to drive weight gain across the population as a whole.

I propose that one possible explanation involves a mechanism I refer to as “intestinal starvation.”

This condition is unlikely to occur due to a single factor alone, but is more likely to arise when the three factors (+1) described below overlap at the same time. For this reason, it may help explain how everyday eating habits and lifestyle patterns—when considered together—can lead to weight gain.

The three factors are as follows:

(1) What you eat

(2) How long you remain hungry until the next meal

(3) The strength of your digestive capacity (such as stomach acid and digestive enzymes)

(1) What you eat

Related terms: low fiber intake, unbalanced diet, refined carbohydrates, easily digestible protein, (ultra-)processed foods, fast food, junk food

A diet that is low in fiber and heavily biased toward refined carbohydrates (starch) and easily digestible protein (even in small amounts) is most likely to trigger intestinal starvation.

Many people try to reduce fat intake when dieting, but lowering the fat content of meals can actually speed up digestion, which may make intestinal starvation more likely rather than less.

In contrast, a well-balanced diet that includes vegetables, fruits, seaweed, legumes, dairy products, nuts, and minimally processed meat or fish is less likely to cause intestinal starvation.

Author: brgfx. Source: Freepik

This idea is consistent with the view that consuming low-GI (glycemic index) foods and minimally processed foods help prevent obesity.

It doesn’t depend on the amount of calories you eat, but the quality and balance of food you eat. For example, eating a variety of foods and having a good balance vs a bad balance may lead to gaining weight, even if you eat small amounts.

Eating speed, how well you chew, and how much fluid you drink during meals may also influence this factor.

【Related article】

The Dilution Effect/ Pushing Out Effect of Carbohydrates

Eating Fat/Oil Can be a Deterrent to Gaining Weight (3 Perspectives Regarding Fat)

(2) Time between meals

Related terms: skipping breakfast or lunch, late dinners, two meals a day, frequency of snacking

Many people report gaining weight due to lifestyle changes such as skipping breakfast or eating dinner late at night. Behind this type of weight gain caused by irregular daily routines lies the issue of long gaps between meals—in other words, enduring hunger for extended periods of time.

Eating late at night does not always lead to weight gain by itself. If dinner has to be late, having a small snack in the early evening—such as nuts, milk, or a sandwich—can help prevent intestinal starvation by avoiding prolonged hunger.

(3) Individual digestive capacity

Related terms: high/low digestive capacity, digestive enzymes, hormones, appetite, gastroptosis (stomach prolapse)

Even when eating the same meals, people with strong stomachs and high digestive capacity may be more likely to experience intestinal starvation than those whose digestion is slower. In today’s society, where energy-dense foods are common, the ability to digest protein and fat may have a particularly strong influence on whether intestinal starvation occurs.

On the other hand, people with sensitive stomachs or conditions such as gastroptosis may find it difficult to fully digest all ingested food in the first place.

If genetic factors contribute to obesity, then the secretion of enzymes and hormones that affect digestive capacity and appetite, as well as the sensitivity of their receptors, is likely to play a major role. Of course, these factors can also change due to environmental and lifestyle influences.

2. This last, but not least important factor: what is “+1”?

In addition to the three factors, I added one more important element as “+1,” which can be explained by “continuity.”

What this means is that not only the meal you have just finished, but also your previous meal and the meals before that can influence whether intestinal starvation occurs or not.