Outline

The Big picture of This Website

I 'd like to introduce the outline of this website to those who visit my website for the first time.

1. Two meanings to the phrase 'gaining weight'

It is generally believed that “taking in too many calories and lack of exercise” are the causes of gaining weight, but I think this theory has a major flaw. In reality, there are two types of weight gain.

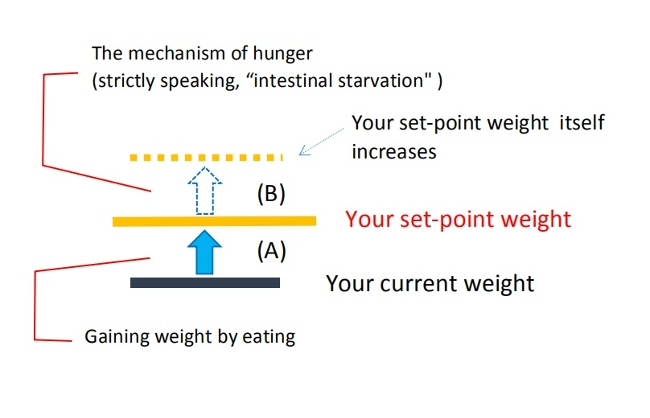

To explain this, I have used the 'set-point' theory regarding body weight, as I believe humans basically have a homeostatic function in the body.

(A): This is the part where many people say, "I gained weight because I ate a lot of calories."

Many individuals prone to weight gain try to reduce their daily caloric intake and/or exercise to keep their weight low because they do not want to gain weight.

In such cases, the body always tries to go back to its set-point, so naturally, eating a lot result in weight gain.

(Temporary overeating may lead to further weight gain beyond the body’s set-point, but I believe this weight gain is temporary and does not alter one’ set- point weight.)

(B): A weight gain in this range means that your set-point weight itself increases. I believe one’s set-point weight goes up through intestinal starvation.

When you feel like you have somehow gained three kilograms in a year or ten kilograms in three years, despite not eating much, it may suggest this weight gain.

In my opinion, the fundamental difference between people who are obese and people who eat a lot but are lean/thin, and also the global obesity issue, is rather a matter of (B).

[Related article]

Two Meanings to the Phrase "Gaining Weight"

2. Why people get fat

I know there are many theories, but let's go with this concept. Human beings evolved tens of thousands of years ago. Considering the original functions of the human body, can’t we think that body fat is a storage mechanism for situation of starvation?

Even the muscles and the brain do not decrease with use. By placing stress on muscles through exercise, they grow stronger and thicker, and athletic performance improves. Similarly, studying enhances thinking and memory skills.

In other words, from the perspective of the human body’s mechanisms, the opposite of the idea that "we get fat because we overeat" should actually hold true.

One finding that supports this is the fact that "being overweight is associated with poverty in some populations."

And also, some of us might have experienced gaining more weight than before, each time we tried dieting-eating less and exercising more.

[Related article]

Wealthy people get fat? Poor people get fat?

However, current theories attribute obesity to overeating and/or lack of exercise. One reason for this is the observation that, in a more affluent society, we can clearly see overweight individuals who eat a lot.

One might say, “If starvation makes us fat, then African refugees should be obese...”

These events seem contradictory at first glance, but I think my theory can resolve them.

3. How do our bodies perceive starvation?

Now, the question is, based on how our body determines that there is no food.

From my experience when I was really thin, it is not that we are starving because of poor nutrition.

The state of all food digested is what our body perceives as "no food." On the other hand, when fiber, fats, oils, and other undigested materials remain in the intestines, our body recognizes that “there is still food.” (I believe it is the entire intestines or small intestine that recognizes all of this).

I call this state of complete food digestion "intestinal starvation." And one’s set-point weight mentioned in section [1] goes up by inducing intestinal starvation.

[Related article] My Definition of “Intestinal Starvation

Make no mistake, this is not the same as mere hunger. In most cases, even when you don’t eat anything for twelve hours, a few traces of undigested food such as fat or fiber remain in your intestines, because our intestines are as long as seven to eight meters (the small intestine is about six meters).

But if you keep eating an unbalanced diet that leans toward carbohydrates and some easily digestible protein, or light meals such as fast food, it’s possible that you can digest all the food in your intestines even in seven to eight hours.

That’s why westernized flour-based diets, fast foods, and processed foods are more likely to induce intestinal starvation, while the traditional rice-based diets found in Asia are said to be less likely to make you fat.

[Related article]

Why Does the Body Perceive That It Is More Starved than in the Past?

4. What is wrong with calorie counting?

A “calorie” is a unit of measure of energy.

In the late 1880’s, it is said that Wilbur Atwater of Wesleyan University was studying what proportion of different foods humans could digest and absorb based on the combustion heat of each food. Based on the Atwater coefficients derived from that study (4 kcal/g for carbohydrates and protein, 9 kcal/g for fat, and 7 kcal/g for alcohol), we still basically calculate calories in food today.

However, these figures were calculated based on a system using an average of subjects and I don’t think it can be applied to everyone. Digestion and absorption are a complex processes, and they vary widely from person to person, so adding up the calories listed on a food label is not strictly meaningful.

Some experts believe that individual differences in digestibility are slight, but I believe that the difference makes a large difference in the various functions of the body.

[Related article]

Why the Atwater Coefficient Is Not Perfect

5. On a caloric basis, people who want to lose weight and those who want to gain weight are doing the opposite of what they should

Food sources that make it easier to induce intestinal starvation are our current foods such as refined carbohydrates, easy-to-digest protein, and processed foods. This is because carbohydrates, when taken with water, expand in the stomach, diluting the concentration of the food eaten and speeding up digestion.

In contrast, eating less digestible foods (such as whole grains, high-fiber vegetables and nuts) and slow- digesting foods (such as dairy, certain proteins, and fats) prevents intestinal starvation (Of course, it differs from person to person). That's why people who eat a balanced diet regularly tend not to gain weight.

Thinking about dieting based on caloric intake, people who want to lose weight tend to avoid calorie-dense foods such as oily foods, and fatty foods.

In addition, they sometimes try to eat light meals or skip meals, which may help them lose weight temporarily, but may result in an increase in set-point weight over the long haul.

Conversely, when some thin people want to gain weight, they tend to choose high-calorie foods even if they don’t eat large portions.

Additionally, they try to eat three meals a day without skipping meals, and often snack on items like cookies or chocolate between meals without hesitation.

However, when thin people eat that way, as a result, some undigested food is left in their intestines throughout the day, and their set-point weight does not change.

In this case-theoretically-the overweight person and the thin person are both doing the opposite of what they hope to achieve, and both tend not to obtain good results.

6. Even if people eat the same way, there are those who gain weight and those who don’t

Of course, even if carbohydrates are likely to induce intestinal starvation and make you gain weight, it does not mean that everyone who eats a big bowl of rice, a big-sized burger, or instant noodles, will gain weight. Some people gain weight even without eating many carbs vs others who never gain weight regardless of eating too many carbs.

I believe that there needs to be at least four determining factors to induce intestinal starvation.

[Related article]→

Three (+one) Factors to Accelerate “Intestinal Starvation”

I used the word "relatively" to explain the reason that some people tend to gain weight while others do not, even if they eat the same way.

For instance, if Mr. A, who weighs eighty kilograms, and Mr. B, who weighs forty-eight kilograms and is thin, eat the exact same food at the same time every day, Mr. A will tend to gain more weight than Mr. B in the long run.

Assuming that Mr. A has stronger digestion, you can say that the person who can digest food faster “eats relatively less.”

On the other hand, people with weak digestion or gastroptosis tend to leave undigested food in their intestines through an entire day, making it difficult for them to gain weight, even if they eat a good amount of food.

[Related article]

What Does It Mean to Eat Relatively Less?

7. Why the timing and frequency of meals affects obesity

In Japan, it is said that a well-balanced breakfast is less likely to make you fat no matter how much you eat, while a late-night meal is more likely to make you fat, though there may be some influence from television.

It is also said that if you skip breakfast and have two meals a day, you are more likely to gain weight.

Of course, this is not true for everyone, but I can explain why this tendency appears with my intestinal starvation theory.

The food we eat is sent from the stomach to the small intestine, and then finally to the rectum over a period of more than ten hours. This means that when we eat and how many times we eat in a day, are also important factors.

I think that the increase in obesity worldwide over the past several decades has been attributed in part to "irregular mealtimes" associated with changes in work, recreation, and other aspects of life.

[Related article]

"When to Eat" Is Important, but It Should Be Paired With "What to Eat"

8. Cause and effect are reversed

According to my theory, having a higher set-point for body weight is fundamentally linked to "increased absorption efficiency," which signifies a state of energy regulation at a higher level. Moreover, this extends to all absorbed nutrients, not just energy sources, but also proteins, minerals, etc.

The muscles that support internal organs, digestive enzymes and hormones are also made from protein, so it is no wonder that bigger and fatter people can digest the same food faster. As a result, these people tend to eat more because they get hungrier and have a greater appetite.

In short, the cause and effect are sometimes reversed: people do not always get fat because they eat more, but because they are bigger and therefore inevitably eat more.

This leads to giving the wrong message to others, including obesity researchers.

[Related article]

After Gaining Weight, We Eat Too Much and Do Less Exercise

9. Genetic factors

It is said that many different genes have been identified as being involved in weight regulation [1], but I believe the ones most strongly influencing it are those related to “digestion and appetite.” (Of course, these abilities can also change due to environmental factors.)

People or ethnic groups with strong digestive systems that can quickly break down food—especially meat and fats—tend to feel hungry more quickly, even if they eat the same amount.

As a result, intestinal starvation is more likely to be induced, and they have a tendency to gain weight over the long term.

The role of genes in weight regulation cannot be ignored, but considering the global obesity epidemic since the 1970’s, genetics alone cannot fully explain it. Although evidence from research in the field of epigenetics is gradually increasing, it is difficult to believe that our collective genes could change significantly over a short span of 50 or 100 years [2].

This has led to frequent discussions about how environmental and behavioral factors interact with genetics to cause obesity. What I would like to emphasize is the relationship between "human digestive ability" and "the digestibility of food."

Cooking and food processing techniques have advanced significantly over the past fifty years. We have come to prefer soft, mashed foods that melt in the mouth rather than hard, fibrous ones.

In other words, even if our digestive ability hasn’t changed, I believe that eating relatively easier-to-digest foods makes it more likely for intestinal starvation to occur.

Furthermore, as explained earlier in section 5, focusing solely on “calories” can lead to misunderstandings.

The existence of people who “don’t gain weight no matter how much they eat” or who “end up gaining more weight than before despite dieting” is not due to genetics or constitution. Rather, it is because our current understanding of energy regulation is fundamentally flawed.

10. How to prove my theory

If there are researchers who agree with my ideas, it would be possible to demonstrate that people can gain more weight even with reduced calorie and carbohydrate intake by inducing intestinal starvation.

Ultimately, it would be desirable to conduct an intervention study where subjects are randomly assigned to an intervention group (semi-starvation diet) and a control group (regular diet). However, if you have doubts about the idea of people gaining weight with the semi-starvation diet I propose, it would be fine to confirm that first before proceeding.

As a first step, all we need to do is to gather the bare minimum of ten to fifteen people who don’t gain weight and stay the same, even though they eat a lot. Monitor them for a few weeks. (However, it is difficult to get good results if they have gastroptosis or weak digestion, like me.)

By eating the diet that I will specify for a certain period of time,-at least I believe that-over fifty percent of the test subjects will gain weight dramatically, and then basically maintain that weight. I’m positive that if this experiment is repeated with the same person several times, it is possible, for instance, for a person who initially weighs sixty kilograms to weigh eighty kilograms, and eventually one-hundred kilograms or more.

The following article explains why intestinal starvation makes humans gain weight, but a more detailed explanation can be discussed in person.

[Related article]

Gaining Weight by Intestinal Starvation; What Does It Mean?

<References>

[1] Speakman JR, Levitsky DA, Allison DB, et al. Set points, settling points and some alternative models: theoretical options to understand how genes and environments combine to regulate body adiposity. Dis Model Mech. 2011 Nov;4(6):733-45.

[2] Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Greystone Books, 2016, Page 21.