Topics

01/15/2017

There is No Meaning in Simply Calculating Calories You Consume

-

Contents

-

- The Atwater coefficient is based on averages

- How we digest food and absorb it differs in each person

- Obesity can be explained by the 'set-point' theory for body weight

<The bottom line>

I’d like to talk about how meaningless it is to calculate the accurate caloric intake for the day, and apply it to weight control to lose weight.

It is said that the caloric values of food that we use to calculate caloric intake are based on the Atwater system(the coefficient of 4 kcal/g for protein and carbohydrate, 9 kcal/g for fat, and 7 kcal/g for alcohol), but various problems have been pointed out regarding the accuracy of these factors.

[Related article]

Calorie Calculation: Why the Atwater Coefficient Is Not Perfect

I believe that one of the problems is that digestibility and absorption rates are based on a system of averages, and I would like to explain that. (This article focuses on how people absorb energy differently, and I won’t mention the process after absorption such as the metabolic process or the differences in hormone secretion, etc.)

1.The Atwater coefficient is based on averages

It is said that, "if you take in more calories than your body needs, you will gain weight, and if you burn more calories than you take in, you will lose weight."(Note 1) This message is very simple, and in a way, it sounds very direct.

However, it is dangerous to accept because the phrases "calories your body needs," and "calories you take in," are ambiguous.

It is said that the calories that the body actually expends including basal metabolism are constantly changing[1], and in my opinion, the calories that the body actually absorbs from food are constantly changing as well.

So, I think it is difficult to derive an accurate value by simply comparing total caloric intake and expenditure.

The Atwater coefficient is based on the average energy value that we can absorb from food, but it seems like it has not been investigated how the absorption rate varies depending on what time of day you eat, how often you eat, or how you combine other foods in a meal.

Also, since this factor is calculated from an average of the subjects, it assumes that everyone has the same digestion and absorption ability[2].

<Note 1>

In 1878, German nutritionist Max Rubner crafted what he called the "isodynamic law". The law claims that the basis of nutrition is the exchange of energy, and was applied to the study of obesity in the early 1900s by Carl von Noorden. (Wikipedia [A calorie is a calorie])

2. How we digest food and absorb it differs in each person

Because I was very thin, my digestibility was poor, and I often had gastrointestinal problems. I felt like I was a guinea pig. If I ate too much fatty or fibrous food, my stomach would be upset even after several hours. And if I forced myself to eat my next meal in that state, I felt that I lost even more weight.

In the Atwater coefficient, fat is said to have a caloric value of 9 kcal/g because its physical combustion heat is 9.4 kilo calories and its digestibility coefficient is set at 95% [3], but for people who have trouble digesting it, including myself, that number is meaningless.

In the following, I will explain how our absorption rate varies for an individual based on my experience.

(I) Absorption rate is not constant but increases from hunger or exercise

Some experiments have shown that when people who want to lose weight reduce their caloric intake and semi-starve themselves, their basal metabolic rate also decreases[1], but I do believe that the absorption rate also changes.

The absorption rate should increase during prolonged periods of hunger or after exercise. This, I believe, is true, not only for energy sources but also for all nutrients, including calcium and other micronutrients.

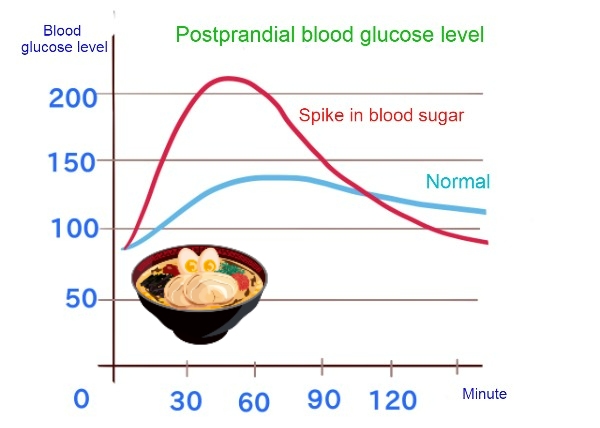

When you are too hungry and tired, your body is working hard trying to take in more nutrients; if you drink alcohol, you may get pretty intoxicated, or if you eat ramen noodles or sweets, your blood sugar level may spike.

To be more specific, even if you reduce the 700 kcal lunch to 400 kcal and eat nothing until dinner, there is still breakfast in your gut, and your intestines wil be working really hard to take in nutrients out of what is left.

Even when the body uses stored energy sources, not all of them lead to a reduction in body fat because some energy sources are used first. In addition, I believe, the more hunger continues, the higher the absorption ability after dinner is, so the body fat should not be reduced as calculated even if the reduced 300 kcal of energy each day is totaled, for instance, for a two-week period.

(The body is said to be in equilibrium with less weight loss than expected, since the basal metabolism also decreases along with weight loss.)

On the contrary, if you continue to force yourself to eat every three to four hours even though you are not feeling hungry, your absorption rate will decrease, relatively speaking. (Of course, it differs from person to person.)

Consider this for instance, after we eat food, it digests for a few hours, and finally, when it is starting to be absorbed, another food comes into the stomach. So, the body will perceive that, “here comes some more food... we can simply take nutrition from that.”

In the previous example of blood glucose, if you eat ice cream two hours before a meal, the rise in blood glucose levels at the meal should slow down.

While a person doing intense exercise with barbells may need to drink protein and milk between meals, the average person doing light exercise may lose weight from this type of eating because the absorption rate decreases, and energy for digestion (diet-induced thermogenesis) is increased, which can be beneficial for weight loss!

(II) The absorption rate varies depending on the combination of foods

How we combine different foods in a meal also makes a difference in hunger and the absorption rate.

As an example, consider a 400 kcal of breakfast (a slice of toast, ham, fried egg). Even if the caloric intake increases, I think adding a burdock salad, cheese, beans, sautéed mushrooms, etc., to breakfast will suppress hunger at lunch and help reduce the rise in blood glucose levels.

I believe it’s partly because that by constantly eating less digestible foods that contain a lot of fiber, and foods that take longer to digest, undigested food will remain in the gut, which suppresses hunger and decreases the absorption rate. It might also be possible that the fiber itself slightly hinders absorption.

Therefore, even if caloric intake is increased, adding these foods to the three daily meals can still be beneficial for dieting.

Conversely, even if caloric intake is reduced, eating only fiber-poor and highly processed foods which are digested quickly give us a lot of energy for very little work[2]. It may increase the absorption rate because of the constant feeling of hunger, and in turn, it may result in repeated ups and downs in blood sugar levels.

(III) Fat does not always make you fat

How we combine macronutrients such as carbohydrates, proteins, and fats in a meal also makes a difference.

Based on calorie theory, we are taught by nutritionists, doctors, and TV programs, that "if you eat a lot of fat, you will get fat" because fat has nine kilo calories of energy per gram.

However, studies have repeatedly shown until the 1970's that diets that reduced carbohydrates and increased protein and fat as much as one wanted, as seen in carbohydrate-restricted diets, had caused weight loss in subjects, even though their daily caloric intake increased[4].

The DIRECT (Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial) study conducted in Israel in 2008 also confirmed that the "Mediterranean Diet" and the "Atkins Diet" (low carbohydrate) had a greater effect on body fat loss than the "low-fat diet" [5 ].

Of course, it is known that the energy to digest protein (diet-induced thermogenesis) is higher and that it makes a difference in the hormones stimulated, but what I’d like to add is the absorption factor.

For the same reason as in section (2) above, a diet that reduces easily digestible refined carbohydrates and relatively increases fats and meats (especially unprocessed slabs or chunks) , etc., may help suppress hunger, decrease absorption rates over time, and be effective for dieting, as undigested food will remain in the intestines for longer periods of time. More benefits should be obtained by incorporating fat into each meal or even between meals as snacks.

Of course, this effect may be less pronounced for people or ethnic groups that can digest fat and protein quickly, but for those who cannot digest fat quickly, including myself, consuming more fat will not cause weight gain.

I believe this may be related to data showing that in the U.S., the rates of obesity defined as having a body mass index of thirty or more increased dramatically from 1977 as a result of the promotion of low-fat diets (high carbohydrate) between 1976 and 1996 [6].

[Related article] Eating Fat/Oil Is a Deterrent to Gaining Weight

3.Obesity can be explained by the 'set-point' theory for body weight

The explanation in section 2 above is how the absorption rate changes in an individual, but as I’ve mentioned throughout this blog, the fundamental difference between overweight and thin people can be explained by the difference in 'set-point' for body weight.

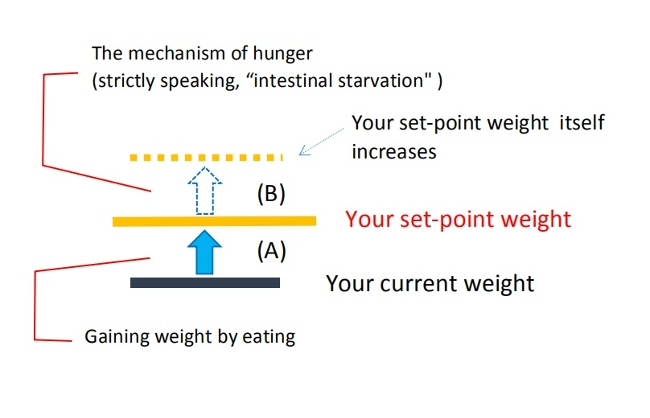

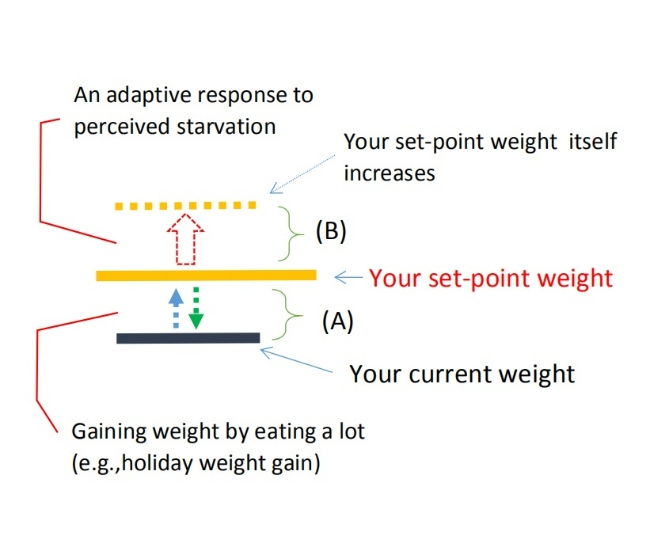

When you gain or lose some weight depending on the amount of calories ingested or burned, I believe it is within the range of [A] ( blue arrow in the figure).

But the increase in set-point weight itself is not directly related to the amount of calories you take in, because it is induced by the intestinal starvation mechanism.

Moreover, according to my theory, having a higher set-point weight is associated with "increased absorption efficiency" compared to a person of average weight. I believe this leads to an overall increase in absorbed nutrients, which means weight gain includes not only body fat but also increased lean mass.

At this point, I can't point out the discrepancy in the Atwater coefficient to explain how one’s set-point for body weight changes, but I would certainly like to prove that people can gain weight due to intestinal starvation.

The bottom line

(1)While it makes sense to calculate daily caloric intake as an average guide in the case of mass food preparation (school lunches, elderly homes, etc.), it does not make much sense to apply it for dieting for each individual. There are many other problems in the concept of being overweight.

(2)The Atwater coefficient is based on the average subject’s ability to digest food , but the process of human digestion and absorption is complex and cannot be described by a system that consist of an average value.

(3)In my opinion, one’s absorption rate varies with how hungry you feel and the intensity of exercise you do. Moreover, what time of the day you eat, meal intervals, and which different foods are combined in a meal also affect the outcome.

(4)I believe that the fundamental cause of being overweight can be explained by the higher set-point weight, and reducing caloric intake may result in temporary weight loss, but in the long run, it will not be effective.

References:

[1] Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Greystone books. 2016. Page 30.

[2] Rob Dunn. Science Reveals Why Calorie Counts Are All Wrong. 2013.

[3] Japan Food Research Laboratories. The Energy Content of Food. 2003 Jul.

[4] Gary Taubes. Why We Get Fat. 2013. New York: Anchor books. Pages 144-158.

[5]Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. 2016. Pages 100-1.

[6]Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. 2016. Pages 19-20.

01/07/2017

Reality Works Opposite of What and How We Think

This time, I would like to explain the relationship between the mind and the mechanism of gaining weight.

Some people who are overweight may start dieting with the thought, " I'm definitely going to lose a few kilos this year.” According to conventional calorie theory, the strategy to do so is to "eat less and/or exercise more.” Many of them first try to avoid high-calorie foods such as oily foods, fried foods, and sweets. Also, they try to skip meals or eat just a little in order to take in fewer calories. In addition to this, some may start jogging or go to a fitness club.

On the other hand, people who are thin tend to think, “I want to gain a little more weight” or “If I skip a meal, I will get thinner.” So, they try not to skip meals and try to eat foods with more calories even though they can’t eat a lot in one sitting.

Then why is it that obese people can’t lose weight even though they reduce caloric intake, but exercise? And why can’t thin people gain weight even though they eat a lot of calories?

It is possible that they are doing the opposite of what is really needed.

“Reality works opposite of what and how we think”

Obese people might get thinner for a while through eating less and exercising more. However, it’s a temporary thing, and over the long haul, it’s not that effective.

With the long periods of hunger caused by restricting meals as in a diet, the intestines improve their absorption ability in order to get the maximum absorption out of a small amount of food. If they don’t eat a balanced diet and their diet leans toward some digestible carbohydrates and protein, the intestinal starvation mechanism may occur. As a result, the 'set-poit' for body weight may go up unknowingly and they’ll find themselves gaining more weight than before. (The rebound effect).

So, it is natural that the success rate of calorie-restricted dieting is low, since they are dieting in the wrong way. It’s not because their efforts were not enough.

(Note: Of course, if you don’t eat anything and exercise, you will lose a lot of weight, but I don’t recommend it. If you don’t take any worthy nutrition when you are working out, the body will catabolize muscle and take minerals out of your bones.)

In contrast, when thin people skip meals, they soon start to get thinner in the face and get tired easily since they don’t have stamina. So, they believe they have to eat something even though they don’t feel so hungry. This is a natural way of thinking for creatures to live...

And that’s why many thin people tend to eat three meals a day and also eat high-calorie foods even if they don’t eat a lot. Also, some people snack between meals without hesitation. There are specialists and some websites that recommend they eat more calories to gain weight.

However, this makes intestinal starvation less likely to occur because undigested food remains in the intestines throughout the day, and the function of the body to store energy will not work. In short, the ‘set-point’ for body weight has not changed. Regardless of the calories they consume, they never gain weight, so they end up saying, “It’s the way I’m made.”

Generally, genetics are used as an excuse to explain the difference between people who eat a lot but never gain weight over the course of their life, and those who tend to gain weight even though they are dieting. Of course, genetics cannot be completely ignored, but since they are theoretically doing the opposite of what they need to do, it is not surprising that both do not work.

To begin with, we need to change the stereotype that "overeating and less exercise” are the causes of weight gain, to stop the obesity epidemic and discover something new.

10/17/2016

Three (+1) Factors That Accelerate “Intestinal Starvation”

-

Contents

-

- Unbalanced diets and irregular lifestyles make intestinal starvation more likely

- This last, but not least important factor, what is “+1”?

1. Unbalanced diets and irregular lifestyles make intestinal starvation more likely

This time, I would like to discuss three key factors-plus one additional factor-that may contribute to the occurrence of what I call “intestinal starvation."

【Related article】

In Japan, the following are often cited to be associated with weight gain other than caloric intake:

(a) An unbalanced diet

• Fast food and junk food

• Excess intake of sugar and carbohydrates

• Lack of vegetables

(b)An irregular lifestyle

• Eating dinner late at night

• Skipping breakfast or lunch

• The frequency and type of snacking

In addition to these, many other factors may also be indirectly involved in the recent increase in obesity. However, it is not always clear how multiple factors combine to drive weight gain across the population as a whole.

I propose that one possible explanation involves a mechanism I refer to as “intestinal starvation.”

This condition is unlikely to occur due to a single factor alone, but is more likely to arise when the three factors (+1) described below overlap at the same time. For this reason, it may help explain how everyday eating habits and lifestyle patterns—when considered together—can lead to weight gain.

The three factors are as follows:

(1) What you eat

(2) How long you remain hungry until the next meal

(3) The strength of your digestive capacity (such as stomach acid and digestive enzymes)

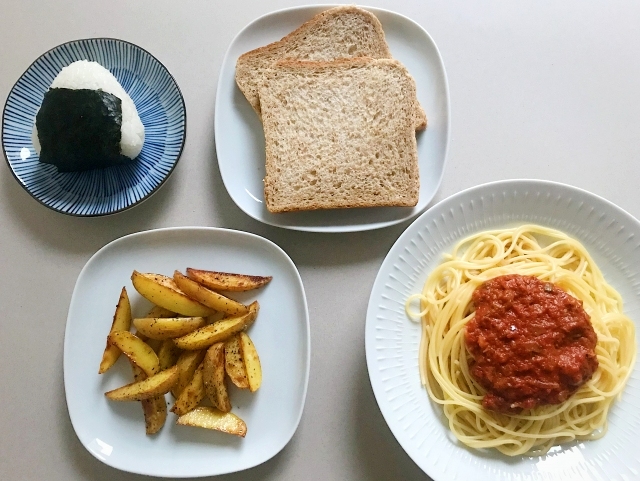

(1) What you eat

Related terms: low fiber intake, unbalanced diet, refined carbohydrates, easily digestible protein, (ultra-)processed foods, fast food, junk food

A diet that is low in fiber and heavily biased toward refined carbohydrates (starch) and easily digestible protein (even in small amounts) is most likely to trigger intestinal starvation.

Many people try to reduce fat intake when dieting, but lowering the fat content of meals can actually speed up digestion, which may make intestinal starvation more likely rather than less.

In contrast, a well-balanced diet that includes vegetables, fruits, seaweed, legumes, dairy products, nuts, and minimally processed meat or fish is less likely to cause intestinal starvation.

Author: brgfx. Source: Freepik

This idea is consistent with the view that consuming low-GI (glycemic index) foods and minimally processed foods help prevent obesity.

It doesn’t depend on the amount of calories you eat, but the quality and balance of food you eat. For example, eating a variety of foods and having a good balance vs a bad balance may lead to gaining weight, even if you eat small amounts.

Eating speed, how well you chew, and how much fluid you drink during meals may also influence this factor.

【Related article】

The Dilution Effect/ Pushing Out Effect of Carbohydrates

Eating Fat/Oil Can be a Deterrent to Gaining Weight (3 Perspectives Regarding Fat)

(2) Time between meals

Related terms: skipping breakfast or lunch, late dinners, two meals a day, frequency of snacking

Many people report gaining weight due to lifestyle changes such as skipping breakfast or eating dinner late at night. Behind this type of weight gain caused by irregular daily routines lies the issue of long gaps between meals—in other words, enduring hunger for extended periods of time.

Eating late at night does not always lead to weight gain by itself. If dinner has to be late, having a small snack in the early evening—such as nuts, milk, or a sandwich—can help prevent intestinal starvation by avoiding prolonged hunger.

(3) Individual digestive capacity

Related terms: high/low digestive capacity, digestive enzymes, hormones, appetite, gastroptosis (stomach prolapse)

Even when eating the same meals, people with strong stomachs and high digestive capacity may be more likely to experience intestinal starvation than those whose digestion is slower. In today’s society, where energy-dense foods are common, the ability to digest protein and fat may have a particularly strong influence on whether intestinal starvation occurs.

On the other hand, people with sensitive stomachs or conditions such as gastroptosis may find it difficult to fully digest all ingested food in the first place.

If genetic factors contribute to obesity, then the secretion of enzymes and hormones that affect digestive capacity and appetite, as well as the sensitivity of their receptors, is likely to play a major role. Of course, these factors can also change due to environmental and lifestyle influences.

2. This last, but not least important factor: what is “+1”?

In addition to the three factors, I added one more important element as “+1,” which can be explained by “continuity.”

What this means is that not only the meal you have just finished, but also your previous meal and the meals before that can influence whether intestinal starvation occurs or not.

For example, suppose you have a light lunch (such as a simple hamburger and coffee), and then you are unable to eat anything at all until 9 p.m.

If your breakfast was also light (for example, toast, a fried egg, and mashed potatoes), the likelihood of intestinal starvation occurring later in the day becomes higher.

On the other hand, if you eat a substantial breakfast that includes vegetables, whole grains, seaweed, beans, and dairy products, the intestinal starvation mechanism is less likely to be triggered (note: of course, individual differences still apply).

Author: brgfx. Source: Freepik

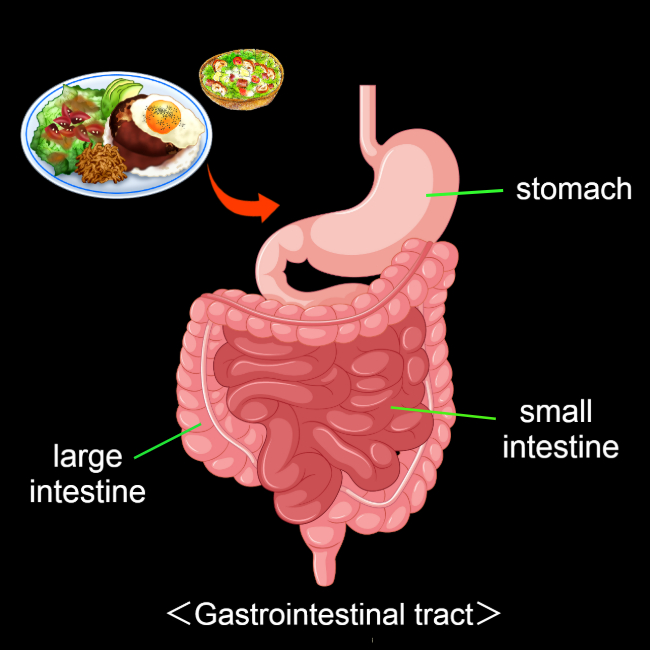

The reason is that the intestines are very long—about 7 to 8 meters in total (with the small intestine alone being about 6 meters)—and it takes, on average, more than ten hours for food to pass through the entire intestinal tract. Because intestinal starvation is judged across the whole intestine (or possibly only the small intestine), it is influenced not only by a single meal, but also by your previous meal and the meals before that.

This is also the flip side of why eating well-balanced meals three times a day is thought to help prevent obesity: it helps ensure that the intestines are continuously exposed to food of adequate quality, reducing the chance that the body interprets the situation as “starvation.”

10/17/2016

Defining “Intestinal Starvation”: Its Relevance to the Multifactorial Model of Obesity

From an evolutionary biology perspective, humans and many other animals are thought to have developed mechanisms to cope with intermittent food shortages over long periods of evolution. Because periods of abundant food were limited, the ability to store energy in the liver, skeletal muscles, and adipose tissue was likely favored by natural selection.

From this viewpoint, obesity can be seen not merely as a consequence of overeating, but as a form of adaptive response in which the body stores energy when it perceives a risk of scarcity.

The concept of “intestinal starvation” adds a new perspective to the discussion of how our bodies perceive a lack of food, moving beyond the traditional focus on energy intake alone.

【Related articles】

Why Does the Body Perceive That It Is More Starved than in the Past?

1.The definition of intestinal starvation

In this work, I use the term “intestinal starvation” to describe a physiological state in which all ingested food has been fully digested along the entire intestinal tract (*1). In this condition, the body interprets the absence of undigested material as a signal of “no food,”regardless of how much food was actually consumed.

This state should be distinguished from severe energy deficit or true food shortage. Unlike those extreme conditions, intestinal starvation may arise under ordinary living circumstances in relatively affluent societies, particularly when diets are dominated by easily digestible foods such as refined carbohydrates, fast-digesting proteins, and various ultra-processed foods (*2).

In this sense, it can be understood as a form of “modern hunger”: a perceived starvation—a signaling state—mediated by the gut–brain axis rather than by a lack of available food in the environment.

(*1) It is unclear whether intestinal starvation is sensed throughout the entire gut or only in the small intestine, which is sometimes referred to as the "second brain."

(*2) Since fats take longer to digest, consuming them every 4 to 5 hours may help prevent the onset of intestinal starvation (e.g., olive oil in the Mediterranean diet). However, during digestion, fats are emulsified into tiny droplets, and once fully digested, they leave no residual material in the gut. In individuals with strong fat-digesting capacity, especially when fats are consumed together with refined carbohydrates, this may not effectively suppress intestinal starvation (e.g., simple hamburgers, potato chips, donuts).

【Related articles】Eating Fat/Oil Can be a Deterrent to Gaining Weight

<Detailed explanation of “how much you eat”>

Even if you consume a large amount of food, a diet composed mostly of refined carbohydrates and other easily digestible items (including certain protein sources and small amounts of fat)—combined with long gaps between meals, such as eating only twice a day—can induce an intestinal starvation state or a condition very close to it.

When carbohydrates are consumed with water, they expand in the stomach (“balloon effect”), dilute the nutrient density of the meal (“dilution effect”), and then pass rapidly from the stomach into the intestine (“push-out effect”).

Because of these combined effects, the body may interpret all ingested food as being “fully digested,” even when a small amount of undigested material technically remains in the intestinal tract.

【Related articles】

The Dilution Effect/ Pushing Out Effect of Carbohydrates

(Refined carbohydrates)

Even when overall food intake is small, a diet composed mainly of easily digestible foods such as refined carbohydrates and certain protein sources (e.g., ultra-processed foods such as simple burgers or sandwiches, or instant noodles) may still trigger intestinal starvation.

Due to recent dieting trends, many people try to keep breakfast or lunch light in an effort to lose weight, but this approach may end up being counterproductive in the long run.

In contrast, when you eat a balanced diet including fiber-rich vegetables, and minimally processed foods three times a day, some fraction of undigested material remains in the intestinal tract continuously throughout the day, making it less likely for intestinal starvation to be induced.

2. Obesity’s multifactorial roots and intestinal starvation

Recent increases in obesity are often attributed to overeating and lack of physical activity.

However, even in environments with abundant food, some people maintain a slim body without dieting, while severe obesity is also observed even among low-income populations in developed countries and in Pacific Island nations with limited resources.

These observations suggest that obesity is a multifactorial condition that cannot be explained by a single factor[1,2]. Genetic factors, diet, physical activity, gut environment, and hormones all interact to influence body weight.

(Source: Freepik)

Since human genes are unlikely to change dramatically over just a few decades, changes in lifestyle and food environments since the 1970s are thought to have played a major role in the recent global rise in obesity[3].

Strictly speaking, four factors(*3) need to overlap for intestinal starvation to be triggered, which may explain why obesity is more likely to occur at the intersection of multiple factors, including genetic, environmental, and physiological factors.

(*3) The four factors are “what you eat,” duration of hunger, digestive ability, and continuity.

Three (+one) Factors to Accelerate “Intestinal Starvation”

(1) Genetic factors

Genetic traits related to intestinal starvation include the secretion capacity and receptor sensitivity of enzymes and hormones that regulate digestion and appetite. In particular, populations or ethnic groups with a greater ability to digest proteins and fats rapidly may be more susceptible to intestinal starvation.

These characteristics may also change as a result of acquired conditions, such as obesity or gastric reduction surgery performed for weight loss.

(2) Environmental factors

Since the 1970s, one of the most notable environmental changes, I believe, has not merely been the increase in energy-dense foods, but rather the rise in easily digestible foods resulting from industrialized food production. Examples include refined carbohydrates, certain protein sources, and ultra-processed foods.

In vegetables and grains, the less digestible parts have been removed (e.g., refined grains), and some are now mashed or strained (e.g., mashed potatoes and potage soups). Meat and fish are often minced or ground, making them easier to digest.

(Author: brgfx / Source: Freepik)

These foods are digested and absorbed more rapidly than traditional, minimally processed foods. As a result, the body can obtain energy more efficiently with less effort, which may also contribute to increased hunger and reduced satiety.

This trend is observed not only in developed countries but also in emerging economies, where the increased consumption of refined carbohydrates and ultra-processed foods has been linked to rising obesity rates.

【Related article】

The Rise in Obesity is Closely Linked to the Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods

<Lifestyle>

Intestinal starvation is related not only to what people eat but also to "how they eat."

Since the 1970s, changes in lifestyle have been accompanied by dramatic shifts in eating habits. In Japan, for example, the traditional rice-based breakfast has gradually been replaced by a Western-style breakfast consisting of toast, coffee, and fried (or boiled) eggs, etc.

In addition, many people now tend to eat light breakfasts and lunches, while consuming the majority of their daily calories at dinner. Such eating patterns may promote intestinal starvation, because our intestines are about seven to eight meters long, and all ingested food may be completely digested while traveling through the intestinal tract.

(3) Physiological factors

Intestinal starvation represents an adaptive physiological response related to intestinal processing and hormonal secretion, and may prove that people who eat a balanced diet every day are likely to be less prone to weight gain

Although intestinal starvation may not be directly associated with the gut microbiota, the types of foods consumed have a significant impact on the intestinal environment.

Individuals who eat a wide variety of foods in a well-balanced manner are less likely to induce intestinal starvation, which may indirectly suggest a relationship that those with a healthier gut microbiota are less susceptible to obesity.

<References>

[1]Flores-Dorantes MT, Díaz-López YE, Gutiérrez-Aguilar R. Environment and Gene Association With Obesity and Their Impact on Neurodegenerative and Neurodevelopmental Diseases. Front Neurosci. 2020 Aug 28;14:863.

[2]Khan MJ et al. Role of Gut Microbiota in the Aetiology of Obesity: Proposed Mechanisms and Review of the Literature. J Obes. 2016;2016:7353642.

[3] Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Greystone Books, 2016, Page 21-2.

03/15/2016

The Two Distinct Processes Behind Weight Gain

-

Contents

-

- When your weight goes back to your set-point weight (A)

- When your set-point weight itself increases (B)

In everyday conversation, “gaining weight” is often understood simply as “an increase in body weight (usually body fat)” compared with the past. However, this expression actually encompasses two physiologically distinct processes.

For example, while it is commonly believed that eating high-calorie foods leads to weight gain, understanding phenomena such as post-diet weight rebound—sometimes resulting in greater weight gain than before—requires a physiological perspective.

I believe that because these two distinct processes are often confused, some misinformation about weight loss have gained popularity, leading many people to diet in ways that may be ineffective or misguided.

【Related article】

The Spread of Dieting May Be Fueling the Rise in Obesity

1. When your weight goes back to your set-point weight (A)

The first type of “gaining weight” comes from the body’s homeostatic drive to return to its set-point weight (Fig. 1A).

Many people who are overweight deliberately try to keep their weight down by reducing their daily caloric intake and/or exercising more.

In such cases, the body continuously pushes back toward its set-point. So it is no surprise that if they begin eating more, their weight naturally increases.

(Note: Temporary overeating may cause the scale to go slightly above one’s set-point, but this weight gain is usually short-lived and does not reflect a change in the set-point itself.)

(Fig. 1)

In many countries, people often talk about “holiday weight gain” or say that high-calorie foods inevitably make them gain weight. Some also claim, “I gain weight as soon as I eat a little more.”

But in most cases, these experiences can be explained by the homeostatic mechanism that pulls body weight back toward its set-point—meaning that the person is simply repeating small cycles of “mini-diets” followed by “mini-rebounds.”

【Related article】

The Set-Point Weight; The Precondition Regarding the Rebound Effect

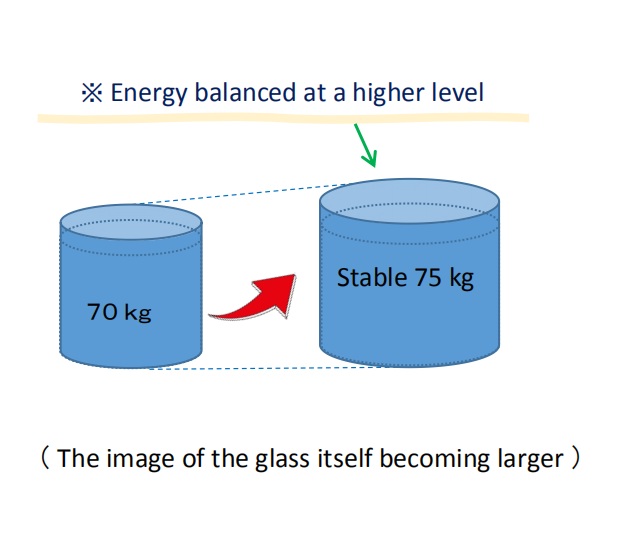

A helpful analogy is a glass of water: the water level may rise or fall temporarily, but the size of the glass itself does not change.

Similarly, when temporary overeating pushes body weight slightly above the set-point, it is like water swelling above the rim of a full glass due to surface tension (Fig. 2).

(Fig. 2) The set-point weight has not changed

2. When your set-point weight itself increases (B)

On the other hand, the second “gaining weight” expression means that one’s set-point weight itself increases (Fig. 1B).

I consider the upward shift in the body’s weight set-point to be driven by a biological adaptive response that occurs when the body perceives a state of starvation—whether due to severe energy deficit from excessive calorie restriction or what I describe in this blog as “intestinal starvation.”

Here, I will focus on the latter: cases in which intestinal starvation appears to raise the set-point.

This often happens to people who try to keep their caloric intake low by eating light breakfasts or lunches—such as a simple burger or a sandwich, or instant noodles—yet still find themselves saying, “I’ve gained three kilos this year… I’m ten kilos heavier than I was three years ago.”

Imagine someone who had never gone above 70 kg but suddenly hits a new high and stabilizes around 75 kg.

In this case, their set-point has effectively shifted from 70 kg to 75 kg, meaning the baseline for balancing energy intake and expenditure itself has moved upward (Fig. 3).

(Fig. 3) The set-point weight itself has increased

I believe this upward shift is not directly related to calories consumed or burned, but rather results from 'intestinal starvation' that can be induced during extended periods of hunger.

【Related article】

Three (+one) Factors to Accelerate “Intestinal Starvation”

An increase in the body’s set-point weight can be thought of as the glass itself growing larger in the aforementioned glass-of-water analogy (Fig. 3). This shift may create a fundamental difference between people who tend to gain weight easily and those who remain lean.

In fact, research on set-point theory suggests that, for some individuals, obesity may represent a “natural physiological state” in which energy balance is maintained at a specific higher set-point.

【Related article】

The Increasingly Important "Set-Point" Theory of Body Weight

From this perspective, the common experience of most people regaining weight after dieting can be understood as a homeostatic, weight-preserving mechanism (A) described above.

However, when someone not only regains weight but surpasses their previous maximum, a different mechanism (B) explained here may be at work. This is because during prolonged calorie restriction, the body may perceive itself to be in a state of starvation.

■Sumo wrestlers in Japan are famous for eating large meals and becoming very heavy. In reality, however, their weight gain can be understood as a mix of mechanisms (A) and (B) described above.

First, through the mechanism of intestinal starvation (B), their body’s weight set-point increases. After that, by eating large meals, their actual body weight rises toward this higher set-point—following the model in (A).

From the outside, it simply looks like they become heavier because they eat a lot, but the underlying process is similar to what happens when someone regains weight after dieting and ends up heavier than before.

【Related article】

Why Are Sumo Wrestlers So Fat?; Six Reasons They’ve Adapted to the Gut Starvation Mechanism

<References>

[1] Richard E. Keesey, Matt D. Hirvonen, Body Weight Set-Points: Determination and Adjustment, The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 127, Issue 9, 1997, Pages 1875S-1883S, ISSN 0022-3166.