Topics

03/15/2016

The Two Distinct Processes Behind Weight Gain

-

Contents

-

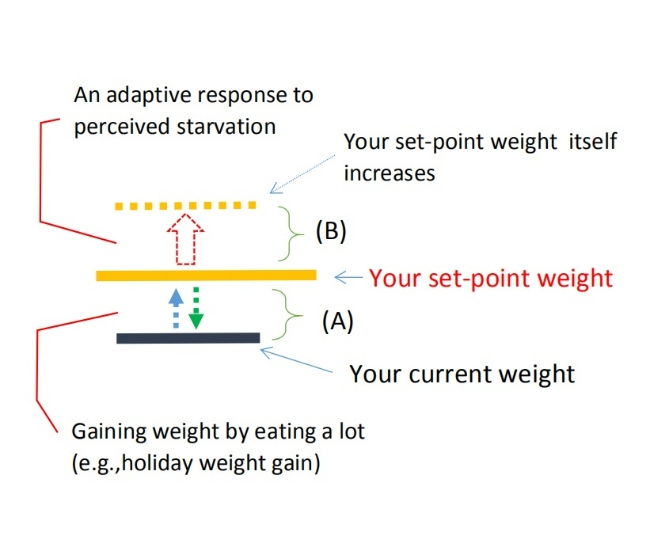

- When your weight goes back to your set-point weight (A)

- When your set-point weight itself increases (B)

In everyday conversation, “gaining weight” is often understood simply as “an increase in body weight (usually body fat)” compared with the past. However, this expression actually encompasses two physiologically distinct processes.

For example, while it is commonly believed that eating high-calorie foods leads to weight gain, understanding phenomena such as post-diet weight rebound—sometimes resulting in greater weight gain than before—requires a physiological perspective.

I believe that because these two distinct processes are often confused, some misinformation about weight loss have gained popularity, leading many people to diet in ways that may be ineffective or misguided.

【Related article】

The Spread of Dieting May Be Fueling the Rise in Obesity

1. When your weight goes back to your set-point weight (A)

The first type of “gaining weight” comes from the body’s homeostatic drive to return to its set-point weight (Fig. 1A).

Many people who are overweight deliberately try to keep their weight down by reducing their daily caloric intake and/or exercising more.

In such cases, the body continuously pushes back toward its set-point. So it is no surprise that if they begin eating more, their weight naturally increases.

(Note: Temporary overeating may cause the scale to go slightly above one’s set-point, but this weight gain is usually short-lived and does not reflect a change in the set-point itself.)

(Fig. 1)

In many countries, people often talk about “holiday weight gain” or say that high-calorie foods inevitably make them gain weight. Some also claim, “I gain weight as soon as I eat a little more.”

But in most cases, these experiences can be explained by the homeostatic mechanism that pulls body weight back toward its set-point—meaning that the person is simply repeating small cycles of “mini-diets” followed by “mini-rebounds.”

【Related article】

The Set-Point Weight; The Precondition Regarding the Rebound Effect

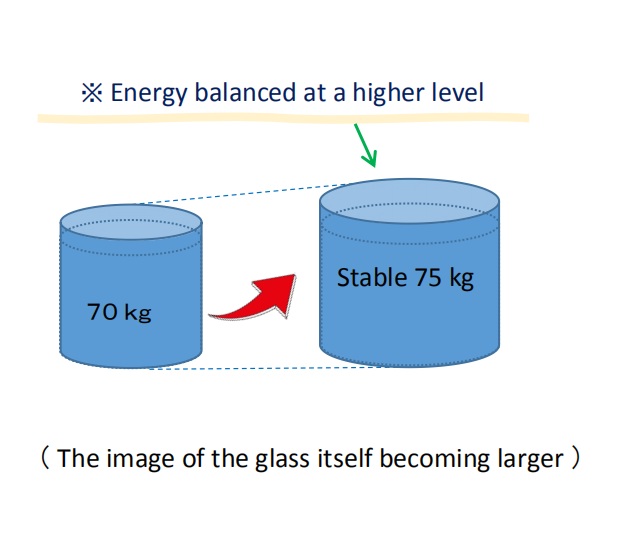

A helpful analogy is a glass of water: the water level may rise or fall temporarily, but the size of the glass itself does not change.

Similarly, when temporary overeating pushes body weight slightly above the set-point, it is like water swelling above the rim of a full glass due to surface tension (Fig. 2).

(Fig. 2) The set-point weight has not changed

2. When your set-point weight itself increases (B)

On the other hand, the second “gaining weight” expression means that one’s set-point weight itself increases (Fig. 1B).

I consider the upward shift in the body’s weight set-point to be driven by a biological adaptive response that occurs when the body perceives a state of starvation—whether due to severe energy deficit from excessive calorie restriction or what I describe in this blog as “intestinal starvation.”

Here, I will focus on the latter: cases in which intestinal starvation appears to raise the set-point.

This often happens to people who try to keep their caloric intake low by eating light breakfasts or lunches—such as a simple burger or a sandwich, or instant noodles—yet still find themselves saying, “I’ve gained three kilos this year… I’m ten kilos heavier than I was three years ago.”

Imagine someone who had never gone above 70 kg but suddenly hits a new high and stabilizes around 75 kg.

In this case, their set-point has effectively shifted from 70 kg to 75 kg, meaning the baseline for balancing energy intake and expenditure itself has moved upward (Fig. 3).

(Fig. 3) The set-point weight itself has increased

I believe this upward shift is not directly related to calories consumed or burned, but rather results from 'intestinal starvation' that can be induced during extended periods of hunger.

【Related article】

Three (+one) Factors to Accelerate “Intestinal Starvation”

An increase in the body’s set-point weight can be thought of as the glass itself growing larger in the aforementioned glass-of-water analogy (Fig. 3). This shift may create a fundamental difference between people who tend to gain weight easily and those who remain lean.

In fact, research on set-point theory suggests that, for some individuals, obesity may represent a “natural physiological state” in which energy balance is maintained at a specific higher set-point.

【Related article】

The Increasingly Important "Set-Point" Theory of Body Weight

From this perspective, the common experience of most people regaining weight after dieting can be understood as a homeostatic, weight-preserving mechanism (A) described above.

However, when someone not only regains weight but surpasses their previous maximum, a different mechanism (B) explained here may be at work. This is because during prolonged calorie restriction, the body may perceive itself to be in a state of starvation.

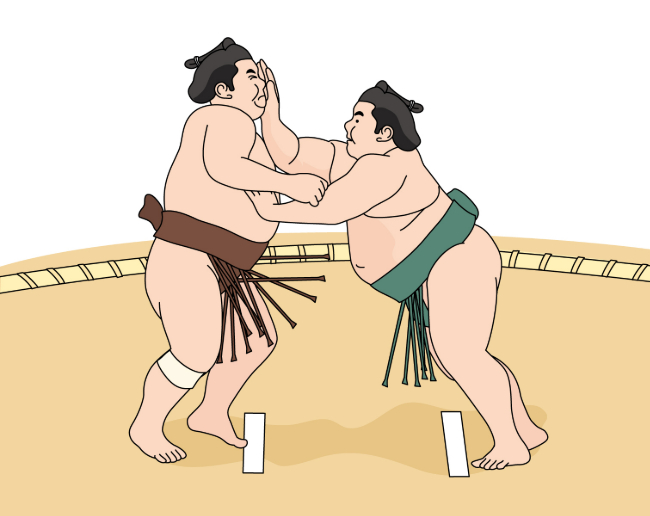

■Sumo wrestlers in Japan are famous for eating large meals and becoming very heavy. In reality, however, their weight gain can be understood as a mix of mechanisms (A) and (B) described above.

First, through the mechanism of intestinal starvation (B), their body’s weight set-point increases. After that, by eating large meals, their actual body weight rises toward this higher set-point—following the model in (A).

From the outside, it simply looks like they become heavier because they eat a lot, but the underlying process is similar to what happens when someone regains weight after dieting and ends up heavier than before.

【Related article】

Why Are Sumo Wrestlers So Fat?; Six Reasons They’ve Adapted to the Gut Starvation Mechanism

<References>

[1] Richard E. Keesey, Matt D. Hirvonen, Body Weight Set-Points: Determination and Adjustment, The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 127, Issue 9, 1997, Pages 1875S-1883S, ISSN 0022-3166.