Topics

02/08/2024

Diabetes (Dysglycemia) is Increasing Despite Decreased Carbohydrate Intake

Contents

- Trends in carbohydrate, fat, and energy intake in Japan(1955-2019)

- Background of the increase in dysglycemia in my opinion

<The bottom line>

If you haven't read the following article yet, please click here to read the original article.

A Low-Carb Diet in Japan:Reducing Carbohydrates Alone is Not the Only Crucial Factor

In this article, I will discuss the causes and background of the relationship between carbohydrate (sugar) intake and the risk of developing diabetes, dysglycemia, etc. in my own way. (The issue of obesity is not discussed in this article.)

1. Trends in carbohydrate, fat, and energy intake in Japan(1955-2019)

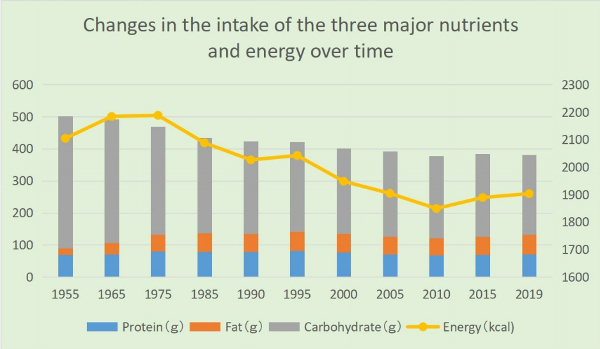

First, based on the National Health and Nutrition Survey conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the daily intake of carbohydrates, fat, and calories among the Japanese are shown below.

・Carbohydrate intake was 411g in postwar 1955, accounting for 78.1% of total energy intake, but it has been declining since then, reaching 280g in 1995 and 248g (52.1% of total energy intake) in 2019.

・As the economy developed in the postwar period, fat intake sharply increased to 50.1g in 1972 but has remained relatively stable around 55g since 1975. Although there was a slight decrease around the year 2000, annual variations after 1975 are not significant.

・Daily energy intake also increased from 2104 kcal in 1955 to 2287 kcal in 1971. However, there has been a decreasing trend since then, reaching 1903 kcal in 2019.

Nevertheless, the number of diabetes patients and those with blood sugar abnormalities continues to rise. The estimated number of diabetes patients (including those strongly suspected of having diabetes [*1]) has been steadily increasing since the survey began in 1997, from 6.9 million to 10 million in 2016.

If pre-diabetics [*2] with abnormal blood sugar are included, the number surpassed 20 million in 2016 (approximately one in six people). (From the 2016 "National Health and Nutrition Survey" in Japan).

[*1] Individuals with an HbA1c level of 6.5% or higher are considered to be "strongly suspected of having diabetes."

[*2] Individuals with an HbA1c level of 6.0% or higher but less than 6.5% are determined to have a "latent diabetes.”

2. Background of the increase in dysglycemia in my opinion

As evident from the above data, the increase in diabetes patients and individuals with blood sugar abnormalities in Japan cannot be solely explained by carbohydrate or caloric intake.

According to Dr. Yamada, the advocate of the low-carb diet, Japanese people have a weaker ability to secrete insulin than Westerners, and many people can have abnormal blood sugar level even if they are not overweight, but other factors I consider are as follows.

(1) Decline in physical activity

As many experts have pointed out, the increase in diabetes patients and those with blood sugar abnormalities is thought to be partially attributed to a decline in physical activity due to the widespread use of PCs, smartphones, video games, etc. (As for obesity, my theory is that decreased physical activity is not directly related to weight gain or obesity.)

(2) Statistical issues

■The National Health and Nutrition Survey selects about 6,000 households by stratified random sampling from designated unit areas. However, in the 2019 survey, it was reported that cooperative households amounted to 2,836, with 5,900 individuals. Since participation is voluntary, there is a tendency for less cooperation among groups such as men, young people, and singles[1].

■There may be a large gap between the upper and lower limits hidden in the averages. While some people follow an ideally balanced diet, others exhibit poor eating habits. In terms of carbohydrate intake, while some people eat fewer carbs due to dieting, people at high risk of lifestyle-related diseases may be consuming excessive amounts of carbs or have an unbalanced diet that leans toward instant foods, fast foods,etc.

(3) Meal frequency, timing, and more

Not only the quantity and quality of meals but also the frequency, timing, and order of consumption can impact absorption.

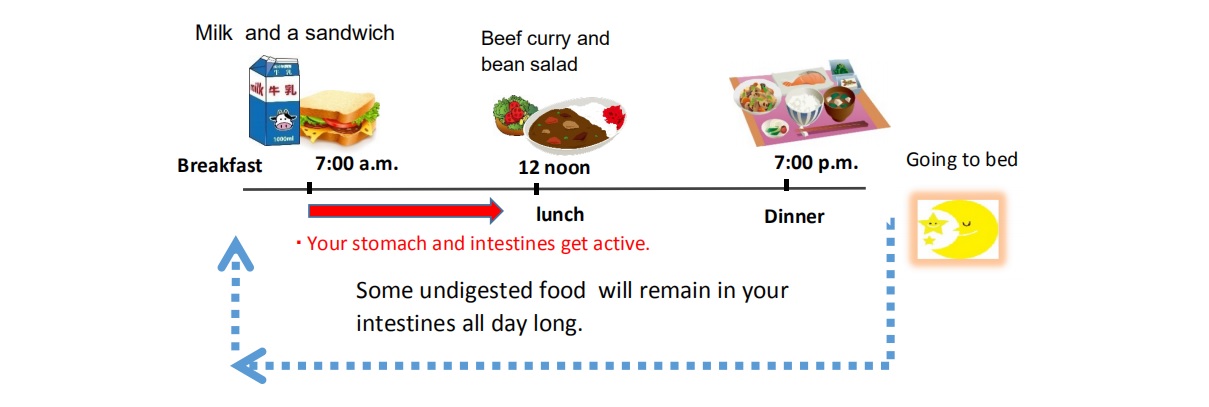

Skipping breakfast and having only two meals a day, even with the same amount of carbs at lunch, is said to increase absorption rates, causing a rapid rise in blood sugar levels after lunch.

In contrast, if you consume foods rich in dietary fiber,etc. at breakfast, it can have an impact on the post-lunch and subsequent meal (second meal) blood sugar elevation. This is known as the "second meal effect," as introduced by Dr. Jenkins from the University of Toronto, in 1982.

(4)Dietary balance

■Maintaining a balanced diet is important. Combining carbohydrates with other food groups such as meat, fish, oils, dairy products, and vegetables (fiber) will prolong gastric retention and moderate sugar absorption. This combination may help in controlling the rapid spike in blood sugar levels even with the same amount of carbohydrates. The tendency of many people to reduce fat intake in order to avoid gaining weight may lead to an increase in individuals with abnormal blood glucose levels as well as obesity.

■Since the 1970s, the rise of nationwide fast-food chains and franchise outlets in the food industry has increased opportunities for quick, convenient meals (such as beef bowls, curry, ramen, and hamburgers). These meals often lack vegetables and consist mainly of carbohydrates, potentially leading to a higher risk of blood sugar spikes.

In addition, many Japanese like to eat carbohydrates. Many set menus combine different types of carbohydrates (rice and wheat products), such as ramen noodles and fried rice.

Even if the amount of carbohydrates is small, combinations such as a rice ball and a snack bread (or instant noodles) can easily raise blood glucose levels.

(5) Quality of carbohydrates

■According to statistics from the Ministry of Agriculture in Japan, the per capita annual consumption of rice peaked at 118 kg in 1962 and has since been on a declining trend. By 2020, the consumption had decreased to less than half, reaching 50.8 kg. In addition, examining trends in annual expenditures per household, the amount spent on bread has exceeded the amount spent on rice since 2014.

While the consumption of rice has sharply decreased in recent years, it's crucial to note that there has likely been an increase in the intake of other carbohydrates that raise blood sugar levels, such as bread, sweets, candies, and soft drinks. Thus, relying solely on data related to “carbohydrate intake” may not provide a comprehensive understanding of the situation. (Reference: Japan Low-Carbohydrate Diet Study Group)

■In this context, the glycemic index (GI), which is quantified by blood glucose level and duration after ingesting a food containing 50 g of carbohydrate, is useful.

In addition, there is another indicator called Glycemic Load (GL), which is calculated by multiplying the percentage of carbohydrates in the target food by the GI value.

From the perspective of suppressing a rapid increase in postprandial blood sugar levels, it is important to focus on foods with a low GI/GL value(*3).

While foods such as white bread, refined rice, boiled potatoes, waffles, and french fries,etc are considered to have high GI values, it is worth noting that, foods like unpolished rice, wholegrain bread, beans, and nuts,etc. have low GI values.

(*3) It is said that foods that cause a rapid surge in blood sugar levels, like sugar, but quickly drop, cannot be adequately represented by the GI value.

■It is known that some starches in food, referred to as “resistant starch,” reach the large intestine without being digested. For instance, some starches found in rice, potatoes, and pasta, after being heated and gelatinized, undergo a structural change when cooled, with a portion turning into resistant starch.

Until around the 1970’s to 1980’s when insulated jars were not as common as they are today, it's likely that many people consumed even more resistant starch from "cooled rice" than they do now.

■In the late 1990’s, the National Cancer Center in Japan conducted a five-year follow-up study to investigate the association between carbohydrate intake and the incidence of typeⅡdiabetes. The study targeted approximately 65,000 men and women aged 45 to 75 with no history of diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, or cancer.

According to the findings, in women, there was a higher incidence of diabetes among those with higher intake of simple carbohydrates (sugar, fructose, etc.) and starches[2].

(6)Evolution of cooking, processed foods, etc

■In recent years, advancements in cooking techniques and the proliferation of processed foods have led to a softening of all types of food, including meat, fish, and vegetables, making them melt in the mouth. In my opinion, such foods, being quickly digested with reduced gastric retention time, may potentially accelerate the absorption of carbohydrates.

■Additionally, many processed foods and sweets often utilize artificial sweeteners. While these sweeteners themselves do not raise blood sugar levels, some experts suggest that their habitual use may impact glycometabolism through changes in taste preferences and alterations in gut microbiota [3][4].

The bottom line

(1) In Japan, since the 1955 statistics, carbohydrate intake has consistently decreased. Caloric intake has also been decreasing over the past fifty years. At least in Japan, the recent increase in diabetes patients and those with blood sugar abnormalities is not solely attributed to carbohydrate or caloric intake.

(2) When it comes to carbohydrates, the way blood sugar levels rise varies. The rapid westernization of the Japanese diet since around 1970 has resulted in a drop in rice consumption in Japan to less than half of its peak level in 1962. Instead, it is thought that the intake of processed wheat products (such as bread, noodles, and snacks) and sugar (sweets and soft drinks), which easily raise blood glucose levels, has increased.

Rice is a grain, and therefore the digestive process should be relatively slower compared to flour-based products, etc. However, even the same type of rice can raise blood glucose levels differently depending on the degree of milling, the cooking method, and the cooling method.

(3) I believe that how blood glucose levels rise is also heavily influenced by dietary balance, the frequency and timing of meals, order of intake, and other dietary habits.

For instance, I suspect that a diet that leans towards easily digestible carbohydrates, frequent intake of sugar, and eating habits such as skipping breakfast or fast eating can increase the frequency of insulin secretion, cause sharp fluctuations in blood sugar levels, and place a burden on the pancreas, even if the carbohydrate intake is not that high.

(4) In order to lower the risk of glucose abnormalities, isn't it important to be aware of not only the carbohydrate content of foods, but also how blood sugar levels rise, such as indicated by the Glycemic Index (GI) and Glycemic Load (GL)?

Reducing the intake of high-GI foods and sugars, and opting for low-GI foods (whole grains, protein-rich foods like meat and fish, nuts, dairy), oils, and non-starchy vegetables, is crucial to reduce overall dietary blood sugar elevation.

It's also known that eating regularly three times a day, starting with vegetables, and consuming cooled rice (resistant starch) can contribute to a gentler increase in blood sugar levels throughout the day.

(5) My personal opinion is that a traditional, well-balanced Japanese diet, with rice as the staple, is less likely to increase the risk of obesity and blood sugar abnormalities. Despite the fact that Japan is blessed with seasonal vegetables, seafood, and traditional fermented foods, I feel that in recent years more and more people are eating high GI carbohydrates, meat products, and instant foods, etc.

(For a comprehensive understanding of the effects of low-carb diets, including their impact on obesity causes, please refer to the following article.)

[Related article] A Low-Carb Diet in Japan:Reducing Carbohydrates Alone is Not the Only Crucial Factor

<References>

[1] Japan Society For The Study Of Obesity. Guidelines for the Management of Obesity Disease 2022. Life Science Publishing Co, Dec.2022, Page28.

[2] Kanehara R et al. Association between sugar and starch intakes and type 2 diabetes risk in middle-aged adults in a prospective cohort study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2022 May;76(5):746-755. doi: 10.1038/s41430-021-01005-1. Epub 2021 Sep 20. PMID: 34545214.

[3] Pepino MY, Bourne C. Non-nutritive sweeteners, energy balance, and glucose homeostasis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011 Jul;14(4):391-5. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283468e7e. PMID: 21505330; PMCID: PMC3319034.

[4] Suez, J., Korem, T., Zeevi, D. et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature 514, 181–186 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13793

02/07/2024

A Low-Carb Diet in Japan:Reducing Carbohydrates Alone Is Not the Only Crucial Factor

Contents

<Introduction>

- What’s Locabo?

- Summary of the effects of “Locabo"

- The increasing prevalence of diabetes in Japan

- Is controlling insulin the key to weight loss?

- The widespread issue of unbalanced and low-quality diets in Japan

<The bottom line>

<Introduction>

In Japan, since around 2015, the low-carb diet-we call "Locabo" based on the English term "a low-carb"-has been catching on among many people. Japan is traditionally a rice-eating culture, but after World War II, more and more people preferred bread and noodles, and with increasingly westernized diets, many feel that we are gaining weight as well.

This time, I’d like to introduce the Locabo diet in Japan, which is believed to be effective not only for losing weight but also for lowering abnormal blood sugar levels and other lifestyle diseases.

<My stance: I will approach the issues of obesity and blood sugar abnormalities separately.>

Generally, experts advocating for carbohydrate restriction seem to believe that the cause of obesity lies not in excessive caloric intake but in carbohydrates (sugars) that elevate blood sugar levels and stimulate insulin (*1) secretion (the carbohydrate-insulin model).

Additionally, it is believed that prolonged insulin resistance or decreased insulin secretion capacity, can lead to abnormal glucose metabolism, ultimately resulting in the development of lifestyle-related diseases such as diabetes.

In other words, both obesity and symptoms like blood sugar abnormalities are thought to be part of a series of events centered around insulin. However, I believe that obesity is caused by different mechanisms related to carbohydrates, so I would like to explain them separately.

(*1) Insulin is a hormone that lowers the level of glucose in the blood. It's released into the blood by the pancreas when the glucose level goes up. Insulin helps glucose enter the body's cells, where it can be used for energy or stored for future use.

1.What’s Locabo?

"In Japan, the phrase “carbohydrate restriction diet” has been generally used, but the word “restriction” has a somewhat negative image. Therefore, we had to use some different words. We came up with the new word “Locabo” after the English phrase “low-carb” and then it spread throughout Japan.

Locabo is not strict but rather a loose carbohydrate restriction. By definition, the diet tries to keep the carbohydrate intake amount per day to around seventy to one hundred and thirty grams in total, by taking twenty to forty grams per meal, three times a day and also a dessert or sweets up to ten grams.

The difference from a strict carbohydrate restriction is that by eating at least seventy grams of carbohydrates, it avoids an extremely low-carbohydrate condition that results in “Ketosis.”

Also, a strict carbohydrate restriction diet makes food choices very limited, but Locabo has a variety of foods you can enjoy. As long as you keep adjusting carbohydrate intake, you can eat a variety of foods such as meat, fish, cheese, and vegetable dishes without thinking about calories."

[References: Satoru Yamada. The truth of carbohydrate restriction. Gentosha books, Nov. 2015, Page 114]

2. Summary of the effects of “Locabo"

The leading advocate for promoting low-carb diets in Japan is Dr. Satoru Yamada, and summarizing his thoughts, we get the following points:

(1) When blood sugar levels rise due to meals, insulin is secreted from the pancreas. Excessive insulin secretion may potentially lead to weight gain. Japanese individuals have a weaker ability to secrete insulin compared to Westerners, and many people experience blood sugar abnormalities even if they are not overweight. More than half of those who develop typeⅡdiabetes have a BMI less than twenty-five.

(2) The higher the frequency of insulin secretion and the higher the upper limit of blood sugar levels, the greater the burden on the pancreas. Over time, this burden can lead to impaired insulin secretion and the onset of diabetes. Additionally, sharp fluctuations in blood sugar levels may potentially contribute to aging, cell cancerization, cognitive disorders (Alzheimer's), and an increased risk of developing cardiovascular diseases.

(3) The only factor that raises blood sugar levels is carbohydrates. By adopting a low-carb diet, it is possible to moderate the increase in blood sugar levels.

Nutrients such as proteins, fats, and dietary fiber, aside from carbohydrates, have the ability to suppress a rapid rise in blood sugar.

In other words, fried rice can control the rapid increase in blood sugar more effectively than white rice.

(4) The belief that reducing fat intake is essential for health has been unquestionably accepted in Japan for a long time. However, various data from the twenty-first century has revealed that even if one reduces fat consumption, it may not lead to improvements in blood lipid levels or prevent heart disease and obesity.

While trans fats should be avoided, there is no need to unnecessarily restrict other types of fats. As for the intake of animal fat (saturated fat), such as those found in meat, studies indicate that, when limited to the Japanese population, there is no association with the incidence of myocardial infarction or stroke (data from 2013).

(5) Even with reduced carbohydrate intake, the brain can utilize ketones (produced from fatty acids) as an energy source. In cases of extreme carbohydrate restriction, an accumulation of ketones in the body can lead to a shift in blood acidity, potentially causing a condition known as ketoacidosis. Given the associated risks, it is advisable not to engage in extreme carbohydrate restriction.

(6) Very few individuals can sustain strict caloric limits or a low-fat diet over the long term. A more lenient approach to carbohydrate restriction is easier to adhere to since it doesn't require constant caloric monitoring, and it often yields more favorable results compared to other dietary approaches. It is important to broaden the options for individuals, exploring which dietary approach suits them best.

3.The increasing prevalence of diabetes in Japan

According to the National Health and Nutrition Survey, per capita daily intake of carbohydrates has been consistently decreasing for over sixty years. The daily intake of energy, too, increased until the early 1970’s, but has been on a declining trend since then.

Nevertheless, in recent years, the number of diabetics and latent diabetics with abnormal blood sugar levels continues to rise.

For more detailed data on this trend and other factors I can think of other than carbohydrate intake, please refer to the following article.

【Related article】Diabetes is Increasing Despite Decreased Carbohydrate Intake

4. Is controlling insulin the key to weight loss?

In terms of controlling blood sugar levels, I believe a moderately low-carb diet can be effective. However, what about the issue of obesity?

According to Gary Taubes, the author of "Why We Get Fat," the debate over whether "overeating calories" or "carbohydrates" are the cause of weight gain has been ongoing since the early 1800’s. The reason behind this is that with a low-carb diet, individuals were able to lose weight without worrying about the quantity of other calorie sources such as meat and fats.

This contradicted the calorie theory and faced strong opposition from experts who staunchly believed in it and considered fats harmful to the heart[1], but now it is said that recent intervention studies have demonstrated the significant weight loss effects of a low-carb diet[2], solidifying its position in the field.

Experts who advocate for a low-carb diet seem to believe in the carbohydrate-insulin model, suggesting that carbohydrates cause weight gain by raising blood sugar levels and promoting insulin secretion. According to this model, it is deemed acceptable to consume proteins and fats that do not stimulate insulin secretion, as long as carbohydrates are reduced, in order to compensate for calories. However, I find this explanation to be insufficient.

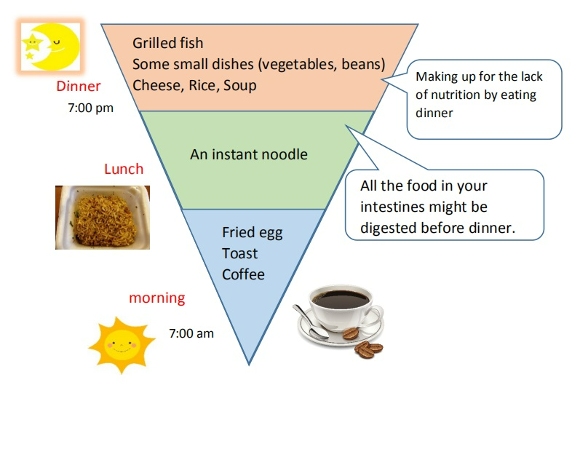

What I would like to add is as follows: a diet leaning towards easily digestible refined carbohydrates and proteins (processed foods) is rapidly digested. As such a diet continues, you feel hungrier, and intestinal starvation is likely to occer.

The characteristics of carbohydrates (dilution effect, push-out effect) further accelerate the occurrence of intestinal starvation.

(In other words, what is related to intestinal starvation are complex carbohydrates such as starch, rice, and flour, not simple carbohydrates like sugar.)

[Related article]

The Dilution Effect/ Pushing Out Effect of Carbohydrates

Therefore, as a countermeasure, we must do the opposite in order to lose weight; not only to reduce carbohydrates to a certain extent but also to increase the intake of foods that take longer to digest (proteins, fats, dairy products, etc.) and foods rich in fiber, so that undigested food will remain abundant in the intestines. (In this regard, the concept of glycemic index [GI] and glycemic load [GL] is very important.)

While advising to consume unlimited amounts of meat and animal fats (saturated fatty acids) doesn't seem accurate, I believe it is important to combine a variety of foods-low-GI carbohydrates, plant-based proteins such as legumes and nuts, unsaturated fatty acids found in fish and plant oils, dairy products, and fibrous vegetables, etc.-to enhance the feeling of fullness.

As a result, the diet may end up resembling a lenient low-carb diet, but my stance is that carbohydrates are not a direct cause of obesity but rather an indirect factor that can induce intestinal starvation. Therefore, I have reservations about strict carbohydrate restrictions such as the ketogenic diet.

Additionally, even if insulin is considered to promote fat storage, I do not believe it is the fundamental cause of obesity.

Some people who advocate a low-carb diet say, "As long as you adjust your insulin secretion, you can eat anything without worrying about calories, even fatty foods, cheese, and meat. And since that's how you lost weight, it was the carbohydrates, not the caloric intake, that was the reason." I don’t think this explanation is correct.

5. The widespread issue of unbalanced and low-quality diets in Japan

In recent years, as the global rise in obesity becomes a significant concern, I believe that for those who tend to gain weight, easily digestible refined carbohydrates are undeniably central factors contributing to weight gain.

However, not everyone gains weight because they eat carbohydrates; factors such as the type of carbohydrates (those with a high GI value), unbalanced diets, and irregular eating habits (such as skipping breakfast or late-night meals) are also associated with the issue.

For instance, focusing solely on caloric and/or carbohydrate "intake," might make it seem like skipping breakfast or opting for simple meals like cup noodles, "snack bread and rice balls," or fast food for lunch is a reasonable choice. It may even appear that not eating vegetables could be somewhat helpful in reducing a few carbs or calories.

However, repeatedly consuming a “low-quality diet” low in fiber and nutrients, rich in carbohydrates, and experiencing recurrent hunger, could potentially increase the risk of developing diabetes and blood sugar abnormalities as well as obesity, don't you think?

While I cannot provide data, to the best of my knowledge, there has been a significant decline in the "quality of meals" among temporary laborers in factories and workplaces, and low-income individuals in Japan in recent years.

When trying to cut down on food expenses, carbohydrates are the cheapest source of calories available, offering a temporary sense of satisfaction.

The bottom line

(1) and (2) are summarized from the contents of "Diabetes is Increasing Despite Decreased Carbohydrate Intake."

(1) The number of diabetes patients in Japan has been steadily increasing since the estimated count began in 1997, rising from 6.9 million to reach 10 million in 2016. Including pre-diabetics with blood sugar abnormalities, the total exceeds 20 million in 2016 (approximately one in six people). Compared to Western populations, Japanese people have a weaker ability to secrete insulin, and over half of those who develop typeⅡdiabetes have a BMI lower than 25.

(2) In Japan, there has been a decreasing trend in caloric and carbohydrate intake for over fifty years. At least in the context of Japan, the rise in obesity, diabetes, and blood sugar abnormalities cannot be solely explained by the amount of caloric and carbohydrate intake alone. Factors such as high glycemic index (GI) foods, sugars, unbalanced diets, and irregular lifestyles including not eating breakfast, may be related to this increase.

(3) Focusing solely on caloric and/or carbohydrate intake might make it seem reasonable to skip breakfast, opt for quick and easy meals like instant noodles or fast food for lunch, and even consider eliminating vegetables.

However, a low-quality diet skewed towards easily digestible carbohydrates and repeated bouts of hunger, may not only increase the risk of developing health issues such as blood sugar abnormalities but also contribute to obesity.

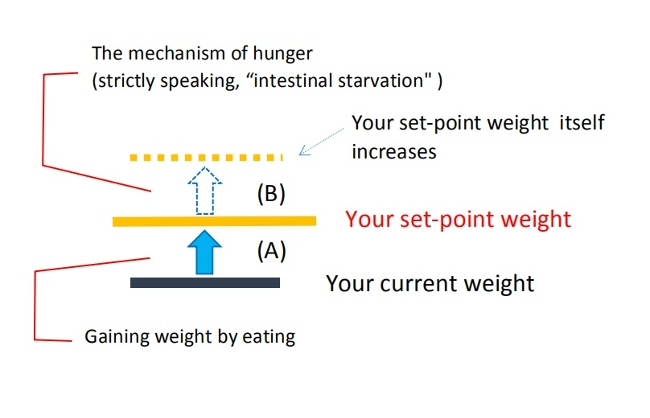

(4) My stance is that the recent increase in (A) the risk of obesity and (B) the prevalence of blood sugar abnormalities is due to the different properties of carbohydrates.

As for (B), the major influence is how a diet containing carbohydrates raises blood glucose levels and its relationship with insulin. In contrast, (A) is associated with easily digestible carbohydrates diluting the food (nutrients) consumed and, under certain conditions, leading to intestinal starvation.

In short, in my theoretical framework, the fundamental issue with obesity is that one’s 'set-point' for body weight goes up through intestinal starvation, and carbohydrates indirectly affect that.

(5) Reducing carbohydrate intake is not the only important factor in decreasing the risk of obesity and blood sugar abnormalities. It is also important to consume low-GI grains, incorporate foods from other food groups (such as meat, fish, vegetables, nuts, dairy, seaweed, etc.) in the diet, and maintain a regular eating schedule (e.g. three meals a day).

All of these practices contribute to slowing down digestion, moderating the speed of absorption, and helping to keep blood glucose levels stable. The concepts of "second meal effect" and "resistant starch" are also important in this regard.

In terms of weight loss, it is crucial to have undigested food consistently remaining in the intestines by consuming more foods that take longer to digest (e.g. proteins, fats) and more fibrous foods.

This approach helps reduce the sensation of hunger, leading to a gradual decrease in absorption rates. Therefore, controlling hunger is, in fact, the key for achieving successful weight loss, in my opinion.

(6) I believe that simple carbohydrates like sugar are significantly related to blood sugar abnormalities. However, the cause of inducing intestinal starvation lies in complex carbohydrates (polysaccharides) such as starch and wheat flour, and not in simple sugars.

<References>

[1] Gary Taubes. Why We Get Fat. New York: Anchor books, 2011, Pages 159-160.

[2] Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Greystone books, 2016, Page 100.

11/03/2023

How Meal Frequency Affects Weight Gain or Loss

Contents

- Background on the relationship between meal frequency and body weight

- Frequency of eating is also related to intestinal starvation

- Conclusion

1. Background on the relationship between meal frequency and body weight

(1) More than fifty years ago, it was reported that lower meal frequency was associated with increased body weight. Since then, a number of observational studies have supported this notion. In a randomized crossover study conducted inside a metabolic chamber, when meal frequency was reduced from three to two meals per day (breakfast and dinner), perceived satiety decreased acutely in lean women[1].

(2) Epidemiological reports have shown a favorable relationship between increased meal frequency, body weight, and metabolic health, and some researchers and nutritionists recognize the consumption of multiple small, regular meals as a dietary approach that may limit weight gain. Increased meal frequency has also been advocated as a dietary strategy to promote weight loss by enhancing satiety and reducing hunger, increasing energy expenditure, and improving metabolic health.

However, intervention trials do not generally support the epidemiological evidence. In today's obesogenic environment, prescribing increased eating opportunities may inadvertently lead to over-consumption and weight gain.

This is especially important in light of recent evidence that more frequent over-consumption of energy-dense foods results in poorer metabolic health[2].

(3) A study using the date from INTERMAP study (International Study on Macro/Micro nutrients and Blood Pressure), conducted four times between 1996 and 1999, suggests that a larger number of small meals may be associated with improved diet quality and lower BMI.

Participants with an average of 6 EO (eating occasion) had higher DQI (diet-quality indices) and lower BMI compared to those with <4 EO, indicating that frequency reflected of a pattern of overall health-promoting behaviours[3].

(4) Conversely, in a study based on data from 50,660 relatively healthy North American adult members aged ≥30 years (Adventist Health Study), eating more than three meals per day (snacking) was associated with a relative increase in BMI, implying that increased EO was associated with increased energy intake[4].

Given these considerations, eating frequency appears to be a secondary factor to the context of energy balance and broader health-promoting behavioural patterns[5].

(5) Elucidating human dietary patterns presents challenges for nutritional epidemiology. Food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) are generally designed to capture average intake over a specific reference period, rather than timing of meals. However, standardized operational definitions for "meal" and "snack" remain lacking and may result in discordant findings when timing of food intake, frequency and (ir)regularity are the outcomes of interest.

Some researchers apply a minimum energy criterion (i.e. >50 kcal ) to snacks, but meals are characterized by predefined, culturally, and socially-driven labels of ‘breakfast’, ‘lunch’, and ‘dinner’, which vary from culture to culture[6].

2. Frequency of eating is also related to intestinal starvation

Some experts say that, “if the total daily caloric intake is the same, it doesn't matter how many meals a day you eat," but I am positive that how many times you eat definitely affects your weight gain (or loss).

I mentioned that the phrase "gaining weight" has two meanings, and based on that idea, I believe it is relatively easy to explain that. Allow me to explain parts (A) and (B) of the following diagram.

(1) As for part (B), the frequency of eating has a lot to do with it.

Since one's set-point weight itself goes up through intestinal starvation, eating more frequently and in a more spread-out manner, is less likely to result in weight gain. When you feel a little hungry, other foods enter your stomach again, which means that undigested foods are more likely to remain in your gastrointestinal tract.

If a person who is naturally slim or has a medium build maintains such a lifestyle, it is more likely that weight gain will be limited, and this will be consistent with observational studies showing a favorable relationship between increased meal frequency, body weight, and metabolic health.

Conversely, eating less frequently (e.g. two meals a day) and longer intervals between meals can lead to weight gain, depending on the foods you combine.

In my theory, meal frequency is synonymous with "meal intervals" and is one of the necessary conditions for intestinal starvation to be induced. As mentioned in the articles "Breakfast" and "Late Night Eating," two meals a day, with meals skewed toward easily digestible carbohydrates and proteins, and a lack of vegetables and dairy products, etc., can lead to intestinal starvation and an increase in set-point for body weight over time.

This is consistent with an observational study from over fifty years ago, which reported that "lower meal frequency was associated with increased body weight.”

(2) As for part (A), I believe that meal frequency is not really relevant.

This is the part where many people believe that taking in more calories makes you fat, which means going back to their set-point weight. Therefore, it should be the total daily caloric intake or carbohydrate intake that matters, rather than how many meals you eat a day. People who normally keep their weight lower through dieting or who cut excess body fat through workouts can gain weight if their caloric intake is higher than necessary due to increased frequency of eating.

As cited in section 1-(2) above, I believe that the research finding in intervention trials that "prescribing for increased eating opportunities for obese individuals may inadvertently lead to over-consumption and weight gain" applies to this part (A).

3. Conclusion

(1) Based on my theory, I believe I can explain the relationship between meal frequency and body weight more concretely as in section [2] above.

The most important factor in the conditions that cause intestinal starvation is "What to eat," but the meal frequency (meal intervals) can have different effects on body weight, even with the exact same daily intake. While there is no denying the fact that meal frequency is "a secondary factor in the context of energy balance and broader health-promoting behavioural patterns," it is certainly an important factor.

(2)In my opinion, two meals a day tend to make people gain weight-meaning that a person’s set-point weight goes up-but four or five meals a day may also increase their set-point weight.

A friend of mine gained more than ten kilograms by eating four to five meals a day when he was studying for a college entrance exam after he failed the first try. From what I heard, he was very thin in high school, even though he belonged to a judo club, and ate a lot of calories.

When I asked him about his weight gain, he told me that light meals such as hot dogs, rice balls, and instant noodles made up more than half of those meals.

As cited in section 1-(5) above, if the definitions of "meal" and "snack" are vague, and even a light meal that is high in carbohydrates and low in vegetables is counted as "one meal," then there is no point in discussing meal frequency. Even in observational studies using questionnaires, etc., discordant findings can occur.

(3) Depending on the subject of the observational study, mixed results can occur in the relationship between meal frequency and body weight.

If a thin or a person with a medium build eats three well-balanced meals and snacks on doughnuts or cookies between meals, this will not be a reason for an increase in set-point for body weight.

In contrast, a larger or obese person may eat four or five times a day as a result of being too hungry. Assuming that as a person’s body increases in size, the stomach and intestines also increase in size and their digestion gets stronger, therefore, we can say that they will feel hungry faster even if they eat the same food as others.

(4) I have no doubt that increasing the frequency of meals has great potential to help with weight loss.

Of course, one should not eat a diet that leans toward carbohydrates and some meats, such as fast food, ramen noodles, snack breads, etc.

However, I believe, as seen in low-carb diets, it is possible to lose weight by basing the diet with fewer carbohydrates and more from the other food groups such as vegetables, protein, dairy, oils, and nuts. (Even when eating carbohydrates, unrefined rice or whole wheat bread, or al dente pasta,etc. which takes longer to digest, are preferable.)

The key, in my opinion, is to leave more undigested food in your intestinal tract, and to reduce the period of time feeling hunger. I believe that this will not only increase energy expenditure (diet-induced thermogenesis), but also decrease absorption ability.

[Related article]

There Are Two Steps to Lose Weight the Right Way

<References>

[1][2]Hutchison AT, Heilbronn LK. Metabolic impacts of altering meal frequency and timing - Does when we eat matter? Biochimie. 2016 May;124:187-197. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.07.025. Epub 2015 Jul 29. PMID: 26226640.

[3]Aljuraiban GS, et al. The impact of eating frequency and time of intake on nutrient quality and Body Mass Index: the INTERMAP Study, a Population-Based Study. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015 Apr;115(4):528-36.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.11.017. Epub 2015 Jan 22. PMID: 25620753; PMCID: PMC4380646.

[4]Kahleova H et al., Meal Frequency and Timing Are Associated with Changes in Body Mass Index in Adventist Health Study 2. J Nutr. 2017 Sep;147(9):1722-1728. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.244749. Epub 2017 Jul 12. PMID: 28701389; PMCID: PMC5572489.

[5][6]Flanagan A, et al., Chrono-nutrition: From molecular and neuronal mechanisms to human epidemiology and timed feeding patterns. J Neurochem. 2021 Apr;157(1):53-72. doi: 10.1111/jnc.15246. Epub 2020 Dec 10. PMID: 33222161.

10/15/2023

Does Eating Late at Night Really Make You Fat?

Contents

- Recent findings on the association between late night eating and weight gain

- Are late night meals really fattening? (My thoughts)

- It is impossible to explain weight gain with BMAL1.

- Conclusion

In Japan, many people (especially women) tend to avoid eating dinner, or dessert or sweets late at night (after nine p.m.) because they do not want to gain weight.

But does that really make sense? Actually, some people say that they have started eating dinner late at night and gained more weight than before, but I believe that is a misconception.

1. Recent findings on the association between late night eating and weight gain

(1) A cross-sectional study examining 17-year changes in energy and macronutrient intake across eating occasions in the 1946 British birth cohort, reported a greater proportion of energy towards the latter half of the day, and as a population, there has been a shift in the timing of when we eat[1].

In a cohort study of 1,245 non-obese, non-diabetic middle-aged adults, participants who consumed 48% or more of their daily energy intake at dinner were twice as likely to be obese at a six-year follow-up, even after adjusting for variations in energy intake, physical activity, and BMI, etc. at baseline[2].

(2) An increased propensity for weight gain is observed in those with eating occasions extending into the night hours, when the body is usually primed for rest, such as night shift workers and shift workers[3].

A meta-analysis published in 2018 reviewed 28 studies and found that shift workers had a higher frequency of developing abdominal obesity than other obesity types.

Permanent night workers demonstrated a 29% higher risk of obesity/being overweight than rotating shift workers[4].

(3) Previous observational studies in humans have linked late eating with higher obesity risk and lower success rates of dietary and surgical weight loss that could not be explained by differences in reported caloric intake or physical activity. It has been suggested that meal timing itself might influence body weight independent of changes in energy intake and activity-related energy expenditure[5].

(4) A systematic review published in 2017 investigated the relationship between evening energy intake and BMI. Of the 121 relevant articles, ten observational studies and eight clinical trials were included in the systematic review (a total of 102 texts did not meet the review eligibility criteria).

Four of the observational studies showed a positive association with BMI, five showed no association, and one indicated a weak, inverse relationship. The meta-analysis of observational studies showed only a slight trend between greater BMI and greater evening energy intake.

The majority of clinical trials reported that a smaller evening meal produced greater weight loss; however, the meta-analysis showed no significant difference between groups.

(Of note, there is considerable inconsistency in the definition of meal timing, quantification of energy intake, and methods of dietary assessment, suggesting that the heterogeneity of the included studies may have affected the reliability of the study results.)[6]

(5) In a randomized controlled crossover trial published in 2022, sixteen overweight or obese subjects completed two laboratory protocols: one with a strictly controlled early meal schedule, and the other with the exact same meals, each scheduled about four hours later in the day.

The results showed that late eating increased hunger, decreased energy expenditure, and affected molecular pathways in adipose tissue.

This study aimed to investigate the direct effect of meal timing, so other effects were isolated by controlling for confounding variables such as caloric intake, physical activity, sleep, and light exposure. But in real life, many of these factors may themselves be influenced by meal timing[7].

2. Are late night meals really fattening? (My thoughts)

If protein and fat synthesis is stimulated more when sleeping, by hormones and other factors, it is not surprising that, in a sense, everyone is somewhat more likely to gain weight at night than in the morning or afternoon. That further complicates the issue. However, I don’t think It is always correct to associate night time eating with an increased risk of obesity.

As I mention in the following article, I believe that "meal timing" is not the only important factor in the increased risk of obesity, "what you eat" has to be included. Eating late at night and skipping breakfast are two sides of the same coin, and that such eating habits, when combined with an unbalanced diet, can easily lead to intestinal starvation, making people more likely to gain weight over time. I would like to explain the following four patterns.

[Related article] "When to Eat" Is Important, but It Should Be Paired With "What to Eat"

(1) When each meal is four hours late

As shown in section 1, a short-term intervention trial in 2022 showed that meals scheduled four hours later compared to early meal schedule affects appetite, energy expenditure, and molecular pathways in adipose tissue, but it remains unclear whether it makes people obese in the long run.

I used to work as a cook at a Japanese restaurant, and this is how I timed my meals. I ate a light breakfast around nine a.m., and lunch was served around three p.m. Dinner was after eleven p.m., when the restaurant was closed, but I have seen a few acquaintances who have put on weight because of this.

The typical cooks or employees working in restaurants also generally delay their meals by three to four hours, but if they eat a balanced meal at breakfast and lunch, and the meal intervals are consistent, it is unlikely-at least in Japan-that this will significantly increase their risk of obesity.

Of course, some people do gain weight over time or suddenly, but I believe that it is "what they eat" that matters. If they continue their eating habits, such as eating unbalanced meals leaning toward easily digestible carbohydrates and skipping breakfast, they will be more likely to gain weight over the long haul.

If researchers wanted to investigate whether slim people actually gain weight by continuing this pattern of eating, they could find out by asking restaurant staff to cooperate and having them eat the same meal menu three times a day (breakfast, lunch, and dinner).

(2) Longer intervals between lunch and dinner

I believe that the typical pattern when late eating causes weight gain is that lunch is consumed around noon, and dinner is delayed until around eight or nine p.m.

A friend of mine works in sales for his company. He travels by a car, and he says he usually eats his dinner around eight or nine p.m. He used to be slender, but after he got married, he had less pocket money at his disposal, and sometimes he had to eat simple meals such as ramen/udon noodles or a Japanese beef/chicken rice bowl, etc. for lunch.

He had gained more than ten kilos during the previous two years, but I believe this is more of a problem of having simple lunches skewed toward carbohydrates and putting up with hunger for longer periods of time, rather than having a late dinner.

This is the same as the inverted triangle-type diet described in the breakfast article, in which breakfast and lunch are light, and dinner makes up for the missing nutrients and calories.

In that case, intestinal starvation is more likely to be induced before a late dinner, and the set-point weight may unknowingly go up.

(3)Snacking before bed and skipping breakfast

Also, some people may snack or eat a light meal after dinner but before bed , but perhaps those people are prone to skipping breakfast.

As shown in the quote in section [1], there are observational studies showing that "eating at night increases the risk of weight gain over time," but in my opinion, late eating can also be related to skipping breakfast (having two meals a day) or eating light meals during the day.

If people skip breakfast, and night time meals and lunches are unbalanced leaning toward easily digestible carbohydrates and some protein, with a lack of vegetables, they are more likely to induce intestinal starvation little by little over time.

Conversely, if you consume a well-balanced meal including fibrous vegetables, dairy products, protein, and fat, etc., at an earlier time of the day, you can prevent intestinal starvation because undigested foods will remain in the intestines for a longer period of time.

(4) Night time snacking may not cause weight gain

If people eat regular, well-balanced meals three times a day, every day, then for many of them, I believe eating before bed does not cause much weight gain.

As I mention throughout this blog, if a person who normally moderates their caloric intake eats sweets or ramen noodles late at night, they may gain a few kilograms, but it means their present weight goes back to their set-point weight.

Actually, there are many thin people in Japan, but even if they eat sweets or a light meal before bedtime in addition to their three meals in order to gain weight, it is more likely that they will not gain weight. In fact, I suppose that some of them may even lose weight if they do not have a strong digestive ability (at least for me, this is one hundred percent true).

The reason being that, by nature, it is good to rest your body and your stomach while you sleep, but if you eat before going to bed, your gastrointestinal tract has to continue to work throughout the night (diet-induced thermogenesis).

I suspect that this may be burdensome and result in a decrease in both cellular regeneration and synthesis of protein and lipids.

3. It is impossible to explain weight gain with BMAL1

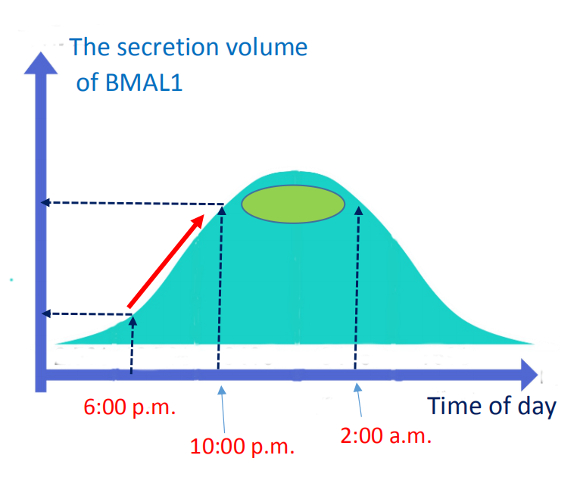

In Japan, some experts explain as if the secretion volume of BMAL1 (Brain and Muscle Arnt-like protein-1 ) and weight gain are correlated. BMAL1 is a protein involved in the biological clock, and is said to be related to adipogenesis.

Its secretion begins to increase around six p.m. and peaks between ten p.m. and two a.m., which seems to be thought of as a rationale behind the fact that people are several times more likely to gain weight if they eat late at night (e.g. ten p.m.) than eating at six p.m. for the same number of calories.

However, I think that explanation is a bit of a stretch. The reason is that the "digestion time" is missing. For example, if they eat a meal at ten p.m., it will take four to six hours for it to be digested and absorbed, depending on the person and how foods are combined, etc. Fats/oils are particularly indigestible, so they may find that even in the morning after seven to eight hours, their food is still undigested and their stomach is upset.

In other words, the time for digestion and absorption is not taken into account, so there is no way to correlate the meal time with the BMAL1 value.

The reason why BMAL1 peaks between ten p.m. and two a.m. is that if we humans have been eating dinner around six p.m. since ancient times, I suspect that BMAL1 levels are also higher so that lipids can be successfully synthesized just as the food is digested and absorbed, and nutrition is transported to all cells in the body.

4. Conclusion

Hormones and other secretions are closely related to circadian rhythms, which differ significantly from day to night. The fact that many other factors come into play further complicates the issue of late night eating and the increased risk of obesity.

However, I believe that the root cause of obesity is due to a higher set-point weight, and here is how "late night eating" can increase one’s set-point for body weight (see Figure-1, B).

(Figure-1)

(1) The phrase "gaining weight" has two meanings. A person who normally moderates their caloric intake in order to lose weight may gain a few kilos overnight if they eat more calories than necessary.

However, this is the case going back to their set-point weight (see Figure-1, A) and should not be confused.

In this case, it should not matter whether the dinner is consumed at seven p.m. or ten p.m.

(2) For a thin or medium-sized person who eats three times a day regularly in a well-balanced manner, I don’t think that additional snacks or light meals before bed are the reason for weight gain and an increased risk of obesity.

Even in the eating patterns where each meal (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) is eaten four hours later than usual as seen in restaurant workers, if they eat a well-balanced diet every day, it is unlikely that this will significantly increase their risk of obesity.

In other words, while an increased feeling of hunger due to eating later than normal may accelerate the onset of intestinal starvation, intestinal starvation is unlikely to occur when there is still plenty of undigested food in the gut.

(3)As in the 2017 review cited in section 1-(4) above, the "relationship between evening energy intake and weight gain (BMI)" could well produce different results depending on the population being studied. This is because late night eating may not lead to weight gain in those who eat a balanced breakfast and lunch (e.g. morning chronotypes).

(4)On the contrary, people who eat late at night may have a habit of skipping breakfast or eating light meals during the day.

If a person eats a well-balanced meal from diverse food groups at breakfast-the first meal of the day when the gastrointestinal tract starts working-, undigested food tends to remain in the intestines for a longer period of time, but they do not eat breakfast, so lunch is their first meal.

If lunch is unbalanced leaning toward easily digestible carbohydrates and some protein, and that dinner is around at eight or nine p.m., people feel hungrier and intestinal starvation is more likely to be induced. These eating patterns are prone to increasing one’s set-point weight in the long run and making people gain weight.

In other words, just because you eat late at night, it does not necessarily lead to obesity. The main problem, in my opinion, is rather unbalanced meals and “prolonged feelings of hunger” over a twenty-four hour period.

(5)If you have to eat dinner late at night, you can snack on milk, sandwiches, nuts, etc. around five p.m. and spread out the meal in order to prevent intestinal starvation. Even if you do not have enough time for breakfast, I think it is important to at least drink milk or café au lait.

(6) In the real world, it is even more difficult to eat a well-balanced meal when trying to eat late at night. In Japan, around eleven p.m., people may end up eating curry, a beef bowl, or ramen noodles from chain restaurants, or a lunch box from a convenience store.

It may be especially difficult for night shift workers to secure well-balanced meals, and I think it may be necessary to conduct observational research focusing on balance from a variety of foods including vegetable intake rather than caloric content.

<References>

[1]Almoosawi S et al. Daily profiles of energy and nutrient intakes: are eating profiles changing over time?. Eur J Clin Nutr 66, 678–686 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2011.210

[2]Bo S et al. Consuming more of daily caloric intake at dinner predisposes to obesity. A 6-year population-based prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014 Sep 24;9(9):e108467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108467. PMID: 25250617; PMCID: PMC4177396.

[3]Davis R et al. The Impact of Meal Timing on Risk of Weight Gain and Development of Obesity: a Review of the Current Evidence and Opportunities for Dietary Intervention. Curr Diab Rep. 2022 Apr;22(4):147-155. doi: 10.1007/s11892-022-01457-0. Epub 2022 Apr 11. PMID: 35403984; PMCID: PMC9010393.

[4]Sun M et al. Meta-analysis on shift work and risks of specific obesity types. Obes Rev. 2018 Jan;19(1):28-40. doi: 10.1111/obr.12621. Epub 2017 Oct 4. PMID: 28975706.

[5][7] Vujović N et al. Late isocaloric eating increases hunger, decreases energy expenditure, and modifies metabolic pathways in adults with overweight and obesity. Cell Metab. 2022 Oct 4;34(10):1486-1498.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.09.007. PMID: 36198293; PMCID: PMC10184753.

[6]Fong M et al. Are large dinners associated with excess weight, and does eating a smaller dinner achieve greater weight loss? A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Nutrition. 2017;118(8):616-628. doi:10.1017/S0007114517002550

09/09/2023

The Reason Why a Well-Balanced Breakfast Helps to Prevent Weight Gain

Contents

- A background of the importance of breakfast in recent years

- How eating breakfast affects weight management? My thoughts

(1) A well-balanced breakfast can help prevent gaining weight

(2) Skipping breakfast makes it easier to gain weight

(3) Lightening your breakfast and lunch makes you more likely to gain weight - Conclusion

In the previous article, I introduced the concepts of a "biological clock," and “chrono-nutrition,” but if you have not read them yet, please read the following article first.

This time, I am going to state my own thoughts on how eating breakfast affects weight management concretely by my intestinal starvation theory.

[Related article]

"When to Eat" Is Important, but It Should Be Paired With "What to Eat"

1. A background of the importance of breakfast in recent years

(1) Observational evidence suggests that there is an association of breakfast eaters with lower body weight (lower BMI) compared to non-breakfast eaters.

However, there is little causal evidence to support this conjecture. Regular breakfast intake is associated with health-promoting behaviors, implying that breakfast intake may be a proxy for health-promoting behaviors. The association in observational studies may reflect a "healthy user bias."[1]

(2) Short-term studies highlight physiological mechanisms by which breakfast may affect body weight, such as appetite, energy expenditure (metabolism), and fat oxidation. However, whether the proposed physiological mechanisms translate to a long-term effect on energy intake and body weight remains unclear[2].

(3) Some hypotheses with regard to breakfast intake and lower body weight speculate that breakfast intake is important for regulating subsequent energy intake. Some studies have shown that skipping breakfast results in higher energy intake at lunch. On the other hand, others suggest that skipping breakfast may not compensate for a need for increased energy intake later in the day, resulting in a decrease in total daily caloric intake relative to when breakfast is consumed[3].

(4) Public health authorities commonly recommend breakfast intake to reduce obesity.

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) in the U.S. in 2014 tested the effectiveness of a recommendation to eat or skip breakfast on weight loss. Approximately 300 overweight or obese adults who trying to lose weight were randomly assigned to one of three groups (control, breakfast, or no breakfast), and the effect of treatment assignment on weight loss was tested in a free-living setting for 16 weeks.

However, this trial showed no effect of a recommendation to eat or skip breakfast on weight loss[4]. In this RCT, the total daily caloric intake, which foods to combine at breakfast, and the timing of meals, etc. were considered free and not specified.

(5) A review of the scientific literature up to 2006 on the "relationship between breakfast habits and body weight and chronic disease risk," analyzed through a MedLine search, pointed to the following issues: Many observational studies have found that breakfast frequency is inversely associated with obesity and chronic disease, but observational studies have some limitations. Only four relatively small, short-term randomized trials have examined breakfast intake and body weight or chronic disease risk, with mixed results.

Measurement of breakfast frequency for the most part is self-reported and subject to each individual's idea of what constitutes breakfast. Therefore, it is possible that the luck of a universal definition for breakfast and measurement of the breakfast has led to conflicting results in some cross-sectional and prospective studies assessing the association between breakfast and obesity and chronic disease risk [5].

2. How eating breakfast affects weight management? My thoughts

I think the concept of “chrono-nutrition” is very important in this day and age, but there are many aspects that cannot be explained by metabolism or hormones alone.

Based on the conventional belief that obesity is caused by "overeating and/or lack of exercise," it does not make sense that people who eat breakfast are associated with lower body weight despite consuming more calories per day than those who skip breakfast. So many researchers have tried to explain the long-term effects of breakfast consumption on body weight by examining the changes in energy expenditure over time when breakfast is consumed or skipped. However, I believe this theory has its limitations.

I think it makes more sense to explain this with my intestinal starvation theory.

As I have mentioned, the phrase "gaining weight" has two meanings, and whether or not breakfast is consumed has a lot to do with the conditions under which intestinal starvation is induced, and it can affect body weight over times in the sense that it can alter one’s set-point weight.

(1) A well-balanced breakfast can help prevent gaining weight

Breakfast is the start of the day, and when you eat breakfast, your resting gastrointestinal tract becomes active.

If you eat a variety of food at that breakfast, such as dairy products, fibrous vegetables, seaweed, legumes, and protein, you can prevent intestinal starvation because undigested food will remain in your intestines for around ten hours or so (this is because our intestines are seven to eight meters long).

Also, if you eat well both at lunch and dinner, you are less likely to gain weight (meaning that your set-point weight does not go up), since there is some undigested food remaining over a twenty-four-hour period in your gastrointestinal tract.

(Typical Japanese breakfast we used to have)

This is the reason why people who are originally slim or medium-sized and have this kind of lifestyle are unlikely to change their body shape throughout their lives, even if they eat without worrying about calories.

However, keep in mind that those who are already overweight will not necessarily lose weight just by eating breakfast (since their set-point weight is already high).

(2) Skipping breakfast makes it easier to gain weight

People who do not eat breakfast may be associated with a nocturnal lifestyle (late night dinner or eating light meals before bed). In short, the main reason for them skipping breakfast may be a lack of appetite or a lack of time to eat.

Not everyone will gain weight if they skip breakfast, but based on my theory, if some conditions are met and overlapped, it makes one more likely to gain weight in the sense that one’s set-point weight increases. If you eat only two meals a day, the interval between meals is longer, so simply what you eat for lunch and dinner has a big impact on the induction of intestinal starvation.

For instance, if you finish dinner at ten p.m., you will not eat for almost fourteen hours until the next day, at noon. Skipping breakfast makes you hungry, so in Japan, people tend to eat lunch with many carbohydrates (rice or noodles) and some meat. Some of them are satisfied with just being full, and their meal may lack fiber and other nutrients.

However, since they have not eaten breakfast, all they have in their gut is that meal at lunch.

If they repeatedly follow a pattern of not eating until eight or nine p.m. in that state, they are likely to induce intestinal starvation little by little, and their set-point weight may go up over time.

Some experts also point out that skipping breakfast and eating a carbohydrate-dense meal when hungry can cause blood glucose levels to spike, leading to high insulin secretion.

This may be true, but in any case, the combination of a "prolonged feeling of hunger" and an unbalanced diet high in carbohydrates and with a lack of vegetables, is likely to increase the risk of obesity and dysglycemia.

You can prevent intestinal starvation by doing the following: if you don't have time to eat in the morning, at least drink some milk, and eat a balanced lunch and dinner with a smaller amount of carbohydrates. And if you have to eat dinner late, eat something such as chocolate or nuts, even around five p.m.

(3) Lightening your breakfast and lunch makes you more likely to gain weight

On the other hand, breakfast can be fattening (in the sense that it increases one's set-point weight) even if one eats it. It is a so-called inverted triangle-type diet, in which breakfast and lunch are light (one might even skip lunch) and dinner makes up for the missing nutrients and calories.

For example, if you just have a light breakfast (a piece of bread, coffee, mashed potatoes, and ham) in the morning, and a rice ball, hamburger, or instant noodles, etc. for lunch, it is easy to induce a intestinal starvation state before dinner, contrary to the situation described in (1) above.

When the gastrointestinal tract becomes active after breakfast, you usually go to the bathroom, and when you do, the only food left in your stomach is what was eaten at breakfast (in this case, mainly carbohydrates and easily digestible protein).

If lunch is also a simple carbohydrate-based meal and lacks fiber and other nutrients, all the food in the intestines will be digested by dinner, which makes it easier to develop a state of intestinal starvation.

In short, if breakfast is well-balanced with choices from the various food groups, you are less likely to gain weight, but if it is a simple and unbalanced one, there is a good chance you will gain weight over the long haul.

Therefore, it is not only a recommendation to eat breakfast, but also to eat a well-balanced one that includes fibrous vegetables, protein, and dairy products, etc.

3. Conclusion

I think what has confused researchers over the years is “whether or not breakfast itself is directly associated with reduced risk of obesity and chronic disease? In other words, is there a causal link there?," and my thoughts, based on the intestinal starvation theory, are as follows:

(1)First, I think it is quite possible that people who usually eat breakfast have other healthy lifestyle habits.

For example, they may eat three times a day regularly, with a well-balanced diet that includes vegetables, dairy products, and protein, etc. throughout the day. They may also exercise religiously, get good quality sleep, and live in accordance with their circadian rhythms.

On the other hand, those who tend to skip breakfast may have a nocturnal lifestyle and poor habits in terms of drinking, smoking, sleeping, and dietary balance.

In short, there might be some confounding factors associated with breakfast.

(2)However, as explained in section [2] above, eating a well-balanced breakfast early in the morning, will prevent intestinal starvation being induced by allowing undigested food in the gastrointestinal tract to remain around ten hours or so. Other health benefits of having undigested food such as fiber and fat in the gut, would include reducing blood sugar spikes and regulating appetite.

On the other hand, an unbalanced breakfast skewed towards easily digestible carbohydrates, proteins, and processed foods, etc. can lead to weight gain, so I do not believe that "breakfast" itself has the effect of deterring weight gain. I’m certain that it is "which foods to combine" at breakfast that matter.

I personally think that if you don't want to eat breakfast, that's fine, but isn't it important to eat lunch and dinner in a balanced manner with a moderate amount of carbohydrates to maintain good health and reduce the risk of obesity?

(3)In my theory, the problem of obesity implies a higher set-point weight, and I believe just eating breakfast does not necessarily lower the set-point weight of a person who is already overweight.

In other words, even if a randomized intervention to "eat or skip breakfast" was conducted in obese or overweight people as in a 2014 U.S. randomized controlled trial (RCT) shown in section [1] above, it may be difficult to demonstrate the benefits of breakfast.

But, this does not mean that breakfast itself is meaningless.

References:

[1]Flanagan A, et al. Chrono-nutrition: From molecular and neuronal mechanisms to human epidemiology and timed feeding patterns. J Neurochem. 2021 Apr;157(1):53-72. doi: 10.1111/jnc.15246. Epub 2020 Dec 10. PMID: 33222161.

[2][3][4]Dhurandhar EJ et al. The effectiveness of breakfast recommendations on weight loss: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014 Aug;100(2):507-13. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.089573. Epub 2014 Jun 4. PMID: 24898236; PMCID: PMC4095657.

[5]Timlin MT, Pereira MA. Breakfast frequency and quality in the etiology of adult obesity and chronic diseases. Nutr Rev. 2007 Jun;65(6 Pt 1):268-81. doi: 10.1301/nr.2007.jun.268-281. PMID: 17605303.