Topics

11/03/2023

How Meal Frequency Affects Weight Gain or Loss

Contents

- Background on the relationship between meal frequency and body weight

- Frequency of eating is also related to intestinal starvation

- Conclusion

1. Background on the relationship between meal frequency and body weight

(1) More than fifty years ago, it was reported that lower meal frequency was associated with increased body weight. Since then, a number of observational studies have supported this notion. In a randomized crossover study conducted inside a metabolic chamber, when meal frequency was reduced from three to two meals per day (breakfast and dinner), perceived satiety decreased acutely in lean women[1].

(2) Epidemiological reports have shown a favorable relationship between increased meal frequency, body weight, and metabolic health, and some researchers and nutritionists recognize the consumption of multiple small, regular meals as a dietary approach that may limit weight gain. Increased meal frequency has also been advocated as a dietary strategy to promote weight loss by enhancing satiety and reducing hunger, increasing energy expenditure, and improving metabolic health.

However, intervention trials do not generally support the epidemiological evidence. In today's obesogenic environment, prescribing increased eating opportunities may inadvertently lead to over-consumption and weight gain.

This is especially important in light of recent evidence that more frequent over-consumption of energy-dense foods results in poorer metabolic health[2].

(3) A study using the date from INTERMAP study (International Study on Macro/Micro nutrients and Blood Pressure), conducted four times between 1996 and 1999, suggests that a larger number of small meals may be associated with improved diet quality and lower BMI.

Participants with an average of 6 EO (eating occasion) had higher DQI (diet-quality indices) and lower BMI compared to those with <4 EO, indicating that frequency reflected of a pattern of overall health-promoting behaviours[3].

(4) Conversely, in a study based on data from 50,660 relatively healthy North American adult members aged ≥30 years (Adventist Health Study), eating more than three meals per day (snacking) was associated with a relative increase in BMI, implying that increased EO was associated with increased energy intake[4].

Given these considerations, eating frequency appears to be a secondary factor to the context of energy balance and broader health-promoting behavioural patterns[5].

(5) Elucidating human dietary patterns presents challenges for nutritional epidemiology. Food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) are generally designed to capture average intake over a specific reference period, rather than timing of meals. However, standardized operational definitions for "meal" and "snack" remain lacking and may result in discordant findings when timing of food intake, frequency and (ir)regularity are the outcomes of interest.

Some researchers apply a minimum energy criterion (i.e. >50 kcal ) to snacks, but meals are characterized by predefined, culturally, and socially-driven labels of ‘breakfast’, ‘lunch’, and ‘dinner’, which vary from culture to culture[6].

2. Frequency of eating is also related to intestinal starvation

Some experts say that, “if the total daily caloric intake is the same, it doesn't matter how many meals a day you eat," but I am positive that how many times you eat definitely affects your weight gain (or loss).

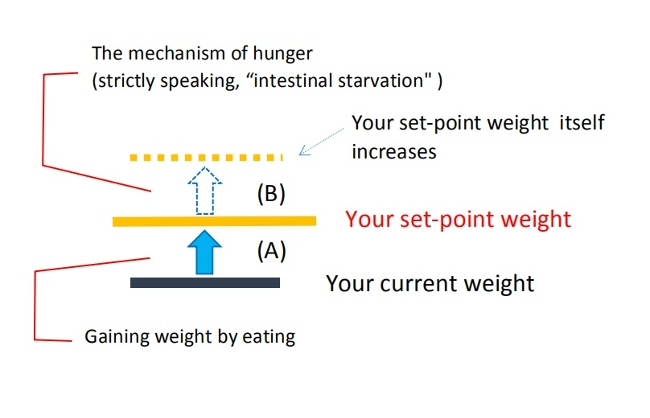

I mentioned that the phrase "gaining weight" has two meanings, and based on that idea, I believe it is relatively easy to explain that. Allow me to explain parts (A) and (B) of the following diagram.

(1) As for part (B), the frequency of eating has a lot to do with it.

Since one's set-point weight itself goes up through intestinal starvation, eating more frequently and in a more spread-out manner, is less likely to result in weight gain. When you feel a little hungry, other foods enter your stomach again, which means that undigested foods are more likely to remain in your gastrointestinal tract.

If a person who is naturally slim or has a medium build maintains such a lifestyle, it is more likely that weight gain will be limited, and this will be consistent with observational studies showing a favorable relationship between increased meal frequency, body weight, and metabolic health.

Conversely, eating less frequently (e.g. two meals a day) and longer intervals between meals can lead to weight gain, depending on the foods you combine.

In my theory, meal frequency is synonymous with "meal intervals" and is one of the necessary conditions for intestinal starvation to be induced. As mentioned in the articles "Breakfast" and "Late Night Eating," two meals a day, with meals skewed toward easily digestible carbohydrates and proteins, and a lack of vegetables and dairy products, etc., can lead to intestinal starvation and an increase in set-point for body weight over time.

This is consistent with an observational study from over fifty years ago, which reported that "lower meal frequency was associated with increased body weight.”

(2) As for part (A), I believe that meal frequency is not really relevant.

This is the part where many people believe that taking in more calories makes you fat, which means going back to their set-point weight. Therefore, it should be the total daily caloric intake or carbohydrate intake that matters, rather than how many meals you eat a day. People who normally keep their weight lower through dieting or who cut excess body fat through workouts can gain weight if their caloric intake is higher than necessary due to increased frequency of eating.

As cited in section 1-(2) above, I believe that the research finding in intervention trials that "prescribing for increased eating opportunities for obese individuals may inadvertently lead to over-consumption and weight gain" applies to this part (A).

3. Conclusion

(1) Based on my theory, I believe I can explain the relationship between meal frequency and body weight more concretely as in section [2] above.

The most important factor in the conditions that cause intestinal starvation is "What to eat," but the meal frequency (meal intervals) can have different effects on body weight, even with the exact same daily intake. While there is no denying the fact that meal frequency is "a secondary factor in the context of energy balance and broader health-promoting behavioural patterns," it is certainly an important factor.

(2)In my opinion, two meals a day tend to make people gain weight-meaning that a person’s set-point weight goes up-but four or five meals a day may also increase their set-point weight.

A friend of mine gained more than ten kilograms by eating four to five meals a day when he was studying for a college entrance exam after he failed the first try. From what I heard, he was very thin in high school, even though he belonged to a judo club, and ate a lot of calories.

When I asked him about his weight gain, he told me that light meals such as hot dogs, rice balls, and instant noodles made up more than half of those meals.

As cited in section 1-(5) above, if the definitions of "meal" and "snack" are vague, and even a light meal that is high in carbohydrates and low in vegetables is counted as "one meal," then there is no point in discussing meal frequency. Even in observational studies using questionnaires, etc., discordant findings can occur.

(3) Depending on the subject of the observational study, mixed results can occur in the relationship between meal frequency and body weight.

If a thin or a person with a medium build eats three well-balanced meals and snacks on doughnuts or cookies between meals, this will not be a reason for an increase in set-point for body weight.

In contrast, a larger or obese person may eat four or five times a day as a result of being too hungry. Assuming that as a person’s body increases in size, the stomach and intestines also increase in size and their digestion gets stronger, therefore, we can say that they will feel hungry faster even if they eat the same food as others.

(4) I have no doubt that increasing the frequency of meals has great potential to help with weight loss.

Of course, one should not eat a diet that leans toward carbohydrates and some meats, such as fast food, ramen noodles, snack breads, etc.

However, I believe, as seen in low-carb diets, it is possible to lose weight by basing the diet with fewer carbohydrates and more from the other food groups such as vegetables, protein, dairy, oils, and nuts. (Even when eating carbohydrates, unrefined rice or whole wheat bread, or al dente pasta,etc. which takes longer to digest, are preferable.)

The key, in my opinion, is to leave more undigested food in your intestinal tract, and to reduce the period of time feeling hunger. I believe that this will not only increase energy expenditure (diet-induced thermogenesis), but also decrease absorption ability.

[Related article]

There Are Two Steps to Lose Weight the Right Way

<References>

[1][2]Hutchison AT, Heilbronn LK. Metabolic impacts of altering meal frequency and timing - Does when we eat matter? Biochimie. 2016 May;124:187-197. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.07.025. Epub 2015 Jul 29. PMID: 26226640.

[3]Aljuraiban GS, et al. The impact of eating frequency and time of intake on nutrient quality and Body Mass Index: the INTERMAP Study, a Population-Based Study. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015 Apr;115(4):528-36.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.11.017. Epub 2015 Jan 22. PMID: 25620753; PMCID: PMC4380646.

[4]Kahleova H et al., Meal Frequency and Timing Are Associated with Changes in Body Mass Index in Adventist Health Study 2. J Nutr. 2017 Sep;147(9):1722-1728. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.244749. Epub 2017 Jul 12. PMID: 28701389; PMCID: PMC5572489.

[5][6]Flanagan A, et al., Chrono-nutrition: From molecular and neuronal mechanisms to human epidemiology and timed feeding patterns. J Neurochem. 2021 Apr;157(1):53-72. doi: 10.1111/jnc.15246. Epub 2020 Dec 10. PMID: 33222161.