Topics

10/15/2023

Does Eating Late at Night Really Make You Fat?

Contents

- Recent findings on the association between late night eating and weight gain

- Are late night meals really fattening? (My thoughts)

- It is impossible to explain weight gain with BMAL1.

- Conclusion

In Japan, many people (especially women) tend to avoid eating dinner, or dessert or sweets late at night (after nine p.m.) because they do not want to gain weight.

But does that really make sense? Actually, some people say that they have started eating dinner late at night and gained more weight than before, but I believe that is a misconception.

1. Recent findings on the association between late night eating and weight gain

(1) A cross-sectional study examining 17-year changes in energy and macronutrient intake across eating occasions in the 1946 British birth cohort, reported a greater proportion of energy towards the latter half of the day, and as a population, there has been a shift in the timing of when we eat[1].

In a cohort study of 1,245 non-obese, non-diabetic middle-aged adults, participants who consumed 48% or more of their daily energy intake at dinner were twice as likely to be obese at a six-year follow-up, even after adjusting for variations in energy intake, physical activity, and BMI, etc. at baseline[2].

(2) An increased propensity for weight gain is observed in those with eating occasions extending into the night hours, when the body is usually primed for rest, such as night shift workers and shift workers[3].

A meta-analysis published in 2018 reviewed 28 studies and found that shift workers had a higher frequency of developing abdominal obesity than other obesity types.

Permanent night workers demonstrated a 29% higher risk of obesity/being overweight than rotating shift workers[4].

(3) Previous observational studies in humans have linked late eating with higher obesity risk and lower success rates of dietary and surgical weight loss that could not be explained by differences in reported caloric intake or physical activity. It has been suggested that meal timing itself might influence body weight independent of changes in energy intake and activity-related energy expenditure[5].

(4) A systematic review published in 2017 investigated the relationship between evening energy intake and BMI. Of the 121 relevant articles, ten observational studies and eight clinical trials were included in the systematic review (a total of 102 texts did not meet the review eligibility criteria).

Four of the observational studies showed a positive association with BMI, five showed no association, and one indicated a weak, inverse relationship. The meta-analysis of observational studies showed only a slight trend between greater BMI and greater evening energy intake.

The majority of clinical trials reported that a smaller evening meal produced greater weight loss; however, the meta-analysis showed no significant difference between groups.

(Of note, there is considerable inconsistency in the definition of meal timing, quantification of energy intake, and methods of dietary assessment, suggesting that the heterogeneity of the included studies may have affected the reliability of the study results.)[6]

(5) In a randomized controlled crossover trial published in 2022, sixteen overweight or obese subjects completed two laboratory protocols: one with a strictly controlled early meal schedule, and the other with the exact same meals, each scheduled about four hours later in the day.

The results showed that late eating increased hunger, decreased energy expenditure, and affected molecular pathways in adipose tissue.

This study aimed to investigate the direct effect of meal timing, so other effects were isolated by controlling for confounding variables such as caloric intake, physical activity, sleep, and light exposure. But in real life, many of these factors may themselves be influenced by meal timing[7].

2. Are late night meals really fattening? (My thoughts)

If protein and fat synthesis is stimulated more when sleeping, by hormones and other factors, it is not surprising that, in a sense, everyone is somewhat more likely to gain weight at night than in the morning or afternoon. That further complicates the issue. However, I don’t think It is always correct to associate night time eating with an increased risk of obesity.

As I mention in the following article, I believe that "meal timing" is not the only important factor in the increased risk of obesity, "what you eat" has to be included. Eating late at night and skipping breakfast are two sides of the same coin, and that such eating habits, when combined with an unbalanced diet, can easily lead to intestinal starvation, making people more likely to gain weight over time. I would like to explain the following four patterns.

[Related article] "When to Eat" Is Important, but It Should Be Paired With "What to Eat"

(1) When each meal is four hours late

As shown in section 1, a short-term intervention trial in 2022 showed that meals scheduled four hours later compared to early meal schedule affects appetite, energy expenditure, and molecular pathways in adipose tissue, but it remains unclear whether it makes people obese in the long run.

I used to work as a cook at a Japanese restaurant, and this is how I timed my meals. I ate a light breakfast around nine a.m., and lunch was served around three p.m. Dinner was after eleven p.m., when the restaurant was closed, but I have seen a few acquaintances who have put on weight because of this.

The typical cooks or employees working in restaurants also generally delay their meals by three to four hours, but if they eat a balanced meal at breakfast and lunch, and the meal intervals are consistent, it is unlikely-at least in Japan-that this will significantly increase their risk of obesity.

Of course, some people do gain weight over time or suddenly, but I believe that it is "what they eat" that matters. If they continue their eating habits, such as eating unbalanced meals leaning toward easily digestible carbohydrates and skipping breakfast, they will be more likely to gain weight over the long haul.

If researchers wanted to investigate whether slim people actually gain weight by continuing this pattern of eating, they could find out by asking restaurant staff to cooperate and having them eat the same meal menu three times a day (breakfast, lunch, and dinner).

(2) Longer intervals between lunch and dinner

I believe that the typical pattern when late eating causes weight gain is that lunch is consumed around noon, and dinner is delayed until around eight or nine p.m.

A friend of mine works in sales for his company. He travels by a car, and he says he usually eats his dinner around eight or nine p.m. He used to be slender, but after he got married, he had less pocket money at his disposal, and sometimes he had to eat simple meals such as ramen/udon noodles or a Japanese beef/chicken rice bowl, etc. for lunch.

He had gained more than ten kilos during the previous two years, but I believe this is more of a problem of having simple lunches skewed toward carbohydrates and putting up with hunger for longer periods of time, rather than having a late dinner.

This is the same as the inverted triangle-type diet described in the breakfast article, in which breakfast and lunch are light, and dinner makes up for the missing nutrients and calories.

In that case, intestinal starvation is more likely to be induced before a late dinner, and the set-point weight may unknowingly go up.

(3)Snacking before bed and skipping breakfast

Also, some people may snack or eat a light meal after dinner but before bed , but perhaps those people are prone to skipping breakfast.

As shown in the quote in section [1], there are observational studies showing that "eating at night increases the risk of weight gain over time," but in my opinion, late eating can also be related to skipping breakfast (having two meals a day) or eating light meals during the day.

If people skip breakfast, and night time meals and lunches are unbalanced leaning toward easily digestible carbohydrates and some protein, with a lack of vegetables, they are more likely to induce intestinal starvation little by little over time.

Conversely, if you consume a well-balanced meal including fibrous vegetables, dairy products, protein, and fat, etc., at an earlier time of the day, you can prevent intestinal starvation because undigested foods will remain in the intestines for a longer period of time.

(4) Night time snacking may not cause weight gain

If people eat regular, well-balanced meals three times a day, every day, then for many of them, I believe eating before bed does not cause much weight gain.

As I mention throughout this blog, if a person who normally moderates their caloric intake eats sweets or ramen noodles late at night, they may gain a few kilograms, but it means their present weight goes back to their set-point weight.

Actually, there are many thin people in Japan, but even if they eat sweets or a light meal before bedtime in addition to their three meals in order to gain weight, it is more likely that they will not gain weight. In fact, I suppose that some of them may even lose weight if they do not have a strong digestive ability (at least for me, this is one hundred percent true).

The reason being that, by nature, it is good to rest your body and your stomach while you sleep, but if you eat before going to bed, your gastrointestinal tract has to continue to work throughout the night (diet-induced thermogenesis).

I suspect that this may be burdensome and result in a decrease in both cellular regeneration and synthesis of protein and lipids.

3. It is impossible to explain weight gain with BMAL1

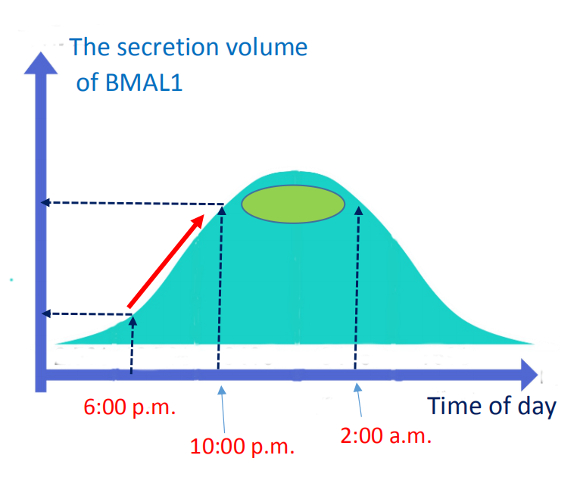

In Japan, some experts explain as if the secretion volume of BMAL1 (Brain and Muscle Arnt-like protein-1 ) and weight gain are correlated. BMAL1 is a protein involved in the biological clock, and is said to be related to adipogenesis.

Its secretion begins to increase around six p.m. and peaks between ten p.m. and two a.m., which seems to be thought of as a rationale behind the fact that people are several times more likely to gain weight if they eat late at night (e.g. ten p.m.) than eating at six p.m. for the same number of calories.

However, I think that explanation is a bit of a stretch. The reason is that the "digestion time" is missing. For example, if they eat a meal at ten p.m., it will take four to six hours for it to be digested and absorbed, depending on the person and how foods are combined, etc. Fats/oils are particularly indigestible, so they may find that even in the morning after seven to eight hours, their food is still undigested and their stomach is upset.

In other words, the time for digestion and absorption is not taken into account, so there is no way to correlate the meal time with the BMAL1 value.

The reason why BMAL1 peaks between ten p.m. and two a.m. is that if we humans have been eating dinner around six p.m. since ancient times, I suspect that BMAL1 levels are also higher so that lipids can be successfully synthesized just as the food is digested and absorbed, and nutrition is transported to all cells in the body.

4. Conclusion

Hormones and other secretions are closely related to circadian rhythms, which differ significantly from day to night. The fact that many other factors come into play further complicates the issue of late night eating and the increased risk of obesity.

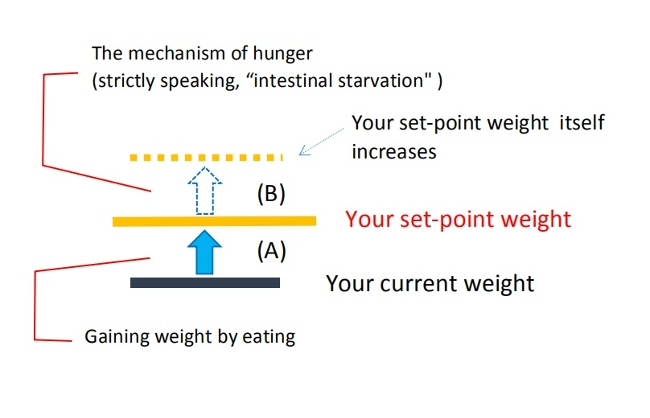

However, I believe that the root cause of obesity is due to a higher set-point weight, and here is how "late night eating" can increase one’s set-point for body weight (see Figure-1, B).

(Figure-1)

(1) The phrase "gaining weight" has two meanings. A person who normally moderates their caloric intake in order to lose weight may gain a few kilos overnight if they eat more calories than necessary.

However, this is the case going back to their set-point weight (see Figure-1, A) and should not be confused.

In this case, it should not matter whether the dinner is consumed at seven p.m. or ten p.m.

(2) For a thin or medium-sized person who eats three times a day regularly in a well-balanced manner, I don’t think that additional snacks or light meals before bed are the reason for weight gain and an increased risk of obesity.

Even in the eating patterns where each meal (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) is eaten four hours later than usual as seen in restaurant workers, if they eat a well-balanced diet every day, it is unlikely that this will significantly increase their risk of obesity.

In other words, while an increased feeling of hunger due to eating later than normal may accelerate the onset of intestinal starvation, intestinal starvation is unlikely to occur when there is still plenty of undigested food in the gut.

(3)As in the 2017 review cited in section 1-(4) above, the "relationship between evening energy intake and weight gain (BMI)" could well produce different results depending on the population being studied. This is because late night eating may not lead to weight gain in those who eat a balanced breakfast and lunch (e.g. morning chronotypes).

(4)On the contrary, people who eat late at night may have a habit of skipping breakfast or eating light meals during the day.

If a person eats a well-balanced meal from diverse food groups at breakfast-the first meal of the day when the gastrointestinal tract starts working-, undigested food tends to remain in the intestines for a longer period of time, but they do not eat breakfast, so lunch is their first meal.

If lunch is unbalanced leaning toward easily digestible carbohydrates and some protein, and that dinner is around at eight or nine p.m., people feel hungrier and intestinal starvation is more likely to be induced. These eating patterns are prone to increasing one’s set-point weight in the long run and making people gain weight.

In other words, just because you eat late at night, it does not necessarily lead to obesity. The main problem, in my opinion, is rather unbalanced meals and “prolonged feelings of hunger” over a twenty-four hour period.

(5)If you have to eat dinner late at night, you can snack on milk, sandwiches, nuts, etc. around five p.m. and spread out the meal in order to prevent intestinal starvation. Even if you do not have enough time for breakfast, I think it is important to at least drink milk or café au lait.

(6) In the real world, it is even more difficult to eat a well-balanced meal when trying to eat late at night. In Japan, around eleven p.m., people may end up eating curry, a beef bowl, or ramen noodles from chain restaurants, or a lunch box from a convenience store.

It may be especially difficult for night shift workers to secure well-balanced meals, and I think it may be necessary to conduct observational research focusing on balance from a variety of foods including vegetable intake rather than caloric content.

<References>

[1]Almoosawi S et al. Daily profiles of energy and nutrient intakes: are eating profiles changing over time?. Eur J Clin Nutr 66, 678–686 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2011.210

[2]Bo S et al. Consuming more of daily caloric intake at dinner predisposes to obesity. A 6-year population-based prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014 Sep 24;9(9):e108467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108467. PMID: 25250617; PMCID: PMC4177396.

[3]Davis R et al. The Impact of Meal Timing on Risk of Weight Gain and Development of Obesity: a Review of the Current Evidence and Opportunities for Dietary Intervention. Curr Diab Rep. 2022 Apr;22(4):147-155. doi: 10.1007/s11892-022-01457-0. Epub 2022 Apr 11. PMID: 35403984; PMCID: PMC9010393.

[4]Sun M et al. Meta-analysis on shift work and risks of specific obesity types. Obes Rev. 2018 Jan;19(1):28-40. doi: 10.1111/obr.12621. Epub 2017 Oct 4. PMID: 28975706.

[5][7] Vujović N et al. Late isocaloric eating increases hunger, decreases energy expenditure, and modifies metabolic pathways in adults with overweight and obesity. Cell Metab. 2022 Oct 4;34(10):1486-1498.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.09.007. PMID: 36198293; PMCID: PMC10184753.

[6]Fong M et al. Are large dinners associated with excess weight, and does eating a smaller dinner achieve greater weight loss? A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Nutrition. 2017;118(8):616-628. doi:10.1017/S0007114517002550