— Topics —

How you eat (Way of intake)

2025.08.15

The Spread of Dieting May Be Fueling the Rise in Obesity

Summary

(1) Alongside the rising prevalence of being overweight and being obese, the prevalence of dieting has also steadily increased over the past several decades. There is concern that dieting may paradoxically be contributing to obesity.

(2) Several observational studies suggest that there is at least a partial causal relationship between dieting and weight gain, while some researchers argue that dieting is merely a proxy marker for a tendency to overeat.

(3) Some prospective studies have found that dieting for weight loss—particularly among adolescents, middle-aged women, and individuals within the normal weight range—is one of the strongest predictors of future weight gain. Social pressure to achieve an ideal slim body, along with a fear of fatness, may drive some people to engage in extreme calorie-restricted diets.

(4) In prospective studies of adolescents, the largest ten-year increases in BMI were observed in both males and females who consistently engaged in unhealthy weight control behaviors, such as skipping meals or eating very little.

Some researchers point out that dieting in adolescence is likely to promote behavior patterns—such as binge eating, skipping breakfast, and insufficient vegetable intake—that are counterproductive to long-term weight management.

<Conclusion>

(5) Some observational studies suggest that dieting itself, independent of genetic factors, may predict an increase in BMI. In long-term clinical studies such as starvation experiments, which involve severe caloric restriction, weight overshooting has also been observed after the restrictions were lifted.

(6) (My thoughts) Not all diets, but some forms of dietary restriction and unhealthy weight control behaviors—such as skipping meals—practiced by certain individuals may be contributing to overall weight gain at the population level.

(7) Weight loss through dietary restriction has been found to trigger a biological starvation response—accompanied by metabolic, hormonal, and neurological changes—which may help explain why body weight can end up higher than the pre-diet level.

【 Full Text 】

-

Contents

-

- Recent trends in dieting and obesity

- Problems and points to note in the observational study

- Is there a causal relationship between dieting and weight gain?

- Conclusion: My thoughts

<Introduction>

In recent years, more and more people around the world are going on diets to lose weight. However, some have raised concerns that dieting itself may be contributing to the rise in obesity.

For example, have you ever noticed that actresses or female TV announcers seem to have gained weight compared to how they looked in the past? To me, it’s hard to believe they’re simply overeating. On the contrary, I suspect they may actually be dieting—such as skipping meals or eating smaller portions—because they don’t want to gain weight.

In this article, I’d like to explore whether there is a link between the prevalence of dieting and the rise in obesity, based on findings from observational and clinical studies.

1. Recent trends in dieting and obesity

(1) In 1992, a panel of experts convened by the U.S. National Institutes of Health concluded: “With continued participation in weight-loss programs conducted in controlled settings, participants typically lose about 10% of their body weight. However, within one year after weight loss, one-third to two-thirds of the weight is regained, and within five years, almost all of it is regained [1].”

In addition, studies on long-term outcomes have shown that at least one-third of dieters regain more weight than they lost [2], raising concerns that dieting may paradoxically be promoting exactly the opposite of what it is intended to achieve[2,3].

(2) The notion that dieting to lose weight is counterproductive for weight control in that people may regain more fat than they lose through each cycle of weight loss/regain was embodied in the 1983 book “Dieting Makes You Fat[4].” Since then, whether dieting leads to weight gain remains a controversial and frequently debated topic among scientists [5,6,7].

(3) As of 1998, Americans spent over $33 billion annually on diet-related products and services [8]. Nevertheless, the prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 30) has steadily increased—from 30.5% in 2000 to 35.7% in 2010, and 42.4% in 2018 [9].

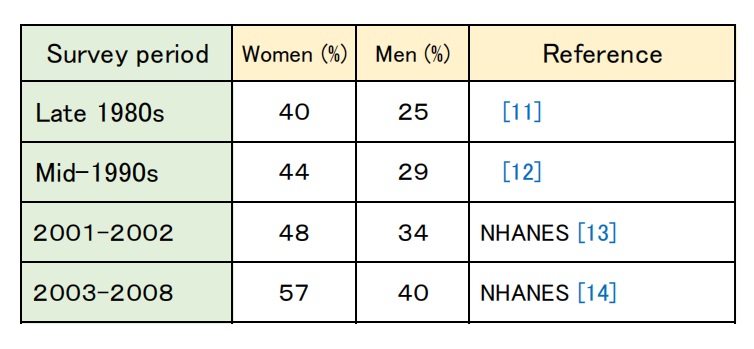

The prevalence of dieting has also continued to rise over the past several decades (see Table 1) alongside the increasing rates of obesity [10].

Table 1: Trends in the prevalence of dieting in the U.S.

In the United Kingdom as well, the age-standardized prevalence of weight loss attempts rose from 39% in 1997 to 47% in 2013.

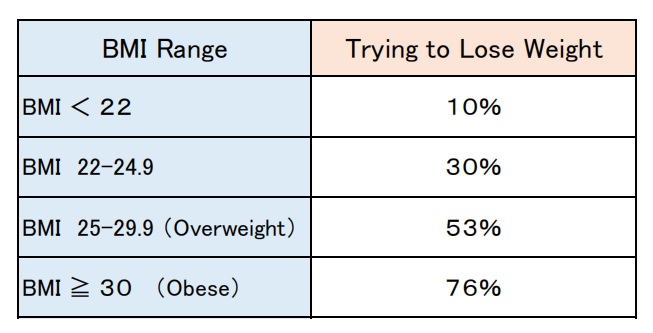

The number of people trying to lose weight has increased each year across all BMI categories [15].

Table 2: Prevalence of weight loss attempts by BMI category (2013,UK)

(4) While some researchers have suggested that the link between dieting and weight gain may be at least partially causal [16,17], others have argued that dieting is a proxy marker for a tendency to overeat and that without dieting, individuals would gain even more weight [18].

(5) Several prospective studies suggest that dieting to lose weight during adolescence [17,19,20], among middle-aged women [21], or by individuals who were initially within the normal weight range [5,21,22] are the strongest and most consistent predictors of future weight gain.

(6) A 10-year prospective study conducted in Minnesota (1998–2009) tracked dieting behaviors and BMI changes among adolescents every five years. A total of 1,902 participants (819 males and 1,083 females) completed the study.

Both males and females who consistently engaged in dieting and unhealthy weight control behaviors (such as skipping meals, eating very little, using food substitutes or diet pills) at both the start of the study (Time 1) and five years later (Time 2) had higher baseline BMIs, and showed greater increases in BMI after ten years (Time 3), as compared to those who did not diet.

Photo Credit: Freepik (photo by Prostooleh)

(*1) 43.7% of females and 18.7% of males reported persistent use (at both Time 1 and Time 2) of unhealthy weight control behaviors.)

In particular, "eating very little" and "skipping meals" were by far the most commonly reported behaviors, and both predicted statistically significant greater BMI increases in both females and males.

Of particular concern was that respondents who were overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30) at Time 1 and continued to engage in dieting or unhealthy weight control behaviors, showed substantial increases in BMI.

For example, overweight females who practiced unhealthy weight control behaviors at both Time 1 and Time 2 experienced an average BMI increase of 5.19 units over the 10-year study period, whereas those who did not use any unhealthy behaviors saw only a 0.15-unit increase [17].

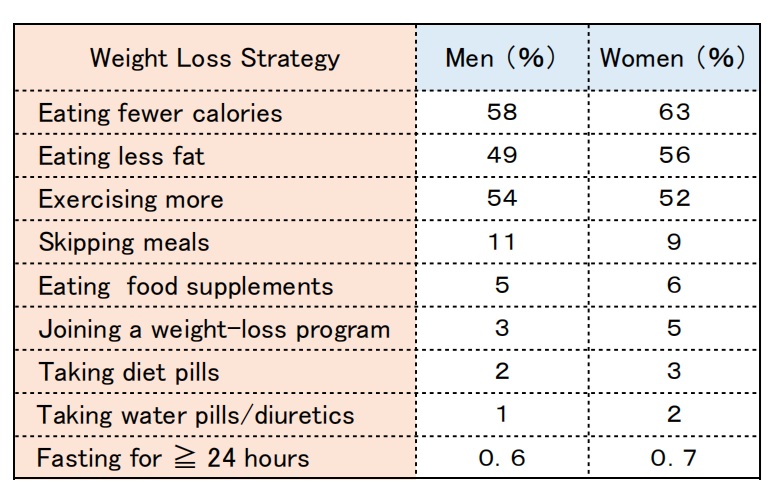

(7) The 1998 U.S. National Health Interview Survey investigated the prevalence of weight loss strategies among U.S. adults (see Table 3).

Only one-third of those attempting to lose weight reported eating fewer calories and exercising more [23].

Table 3: The prevalence of weight loss strategies among U.S. adults (1998)

2. Problems and points to note in the observational study

While the majority of longitudinal observational cohort studies have shown subsequent weight gain among self-report dieters, some of the findings have suggested that dieting predicts both weight loss and weight gain, and the results have not always been consistent.

I would like to explore the possible reasons for this and other important points to consider.

(1) What kind of dieting was involved?

Many studies have examined whether participants were dieting or their history of dieting at the start, but not so many have investigated specific dieting behavior.

Of course, people who followed a healthy and sustainable approach to weight loss—e.g., eating more vegetables, reducing ultra-processed foods, eating breakfast, and exercising—may have been able to maintain their weight loss. On the other hand, those who followed the wrong kind of diet that only produced short-term results may have ultimately ended up failing.

(2) Study duration and timing of dieting

In some studies, dieting status was assessed only at the beginning, and changes in BMI were then tracked several years later (e.g., after 2, 5, or 10 years). However, from a homeostasis perspective, individuals who were dieting at the start of the study may already have had a body weight below their original weight (meaning set-point weight) .

Additionally, if someone begins (or stops) dieting during the study period, or starts dieting shortly before the study ends, it may be difficult to accurately determine the causal relationship between dieting and weight change.

(3) BMI tends to increase during adolescence

An increase in BMI does not necessarily mean an increase in body fat. During adolescence (from junior high through high school), muscle mass also increases significantly, so a certain amount of BMI gain is not unusual. This is something to keep in mind when conducting observational studies in this age group.

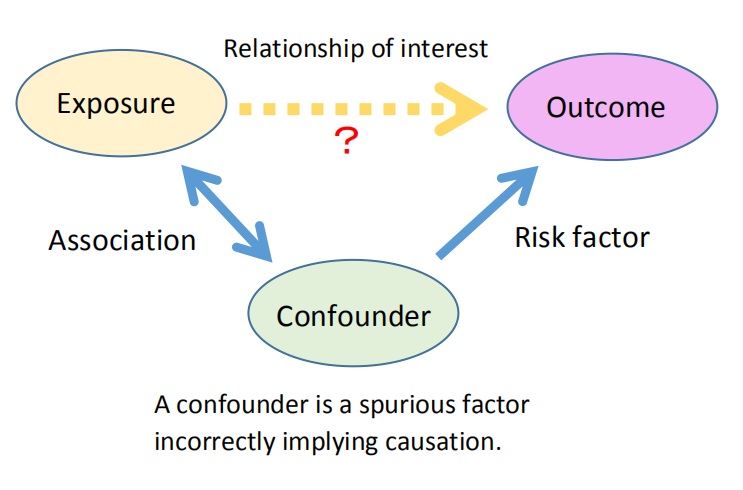

(4) Confounding factors

Confounding factors are variables that can influence the relationship between a specific exposure and an outcome.

For example, when studying the link between alcohol consumption and cancer, smoking is known to increase cancer risk as well. Since people who drink alcohol often smoke, smoking becomes a confounding factor.

When examining the causal relationship between dieting and obesity, it’s important to account for other potential confounding factors (*2).

(*2) For example: alcohol consumption, smoking cessation, lack of physical activity, insufficient intake of calcium or micronutrients, socioeconomic status, childbirth, and sleep deprivation are all associated with weight gain.

3. Is there a causal relationship between dieting and weight gain?

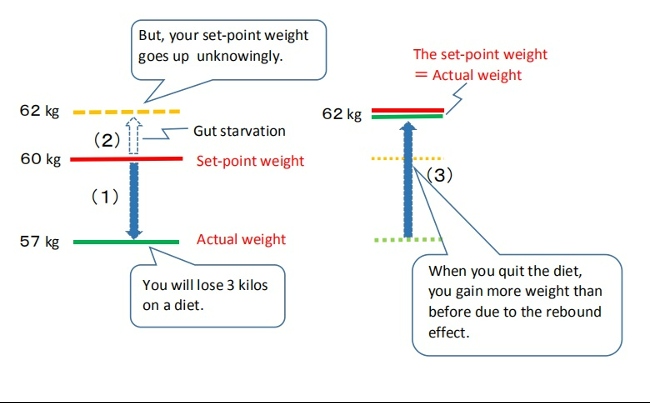

Throughout this blog, I’ve explained that calorie-restricted diets—such as skipping meals—may induce intestinal starvation, which could lead to weight gain-meaning an increase in the body’s set-point weight. So it’s not at all surprising that the rise in dieting may be linked to the rise in obesity.

However, this time, I’d like to set aside my own ideas and explore this causal relationship based on what can be interpreted from observational and clinical studies.

(1) First, let’s look at the claim that “dieting is merely a proxy marker for a tendency to overeat, and without dieting, people would gain even more weight.”

In the 10-year study of adolescents discussed in Section 1-(6), researchers were able to track the trajectories of those who were dieting at the start (Time 1) but either stopped dieting or continued dieting five years later (Time 2).

They found that those who stopped dieting gained significantly less weight compared to those who continued dieting. This finding does not support the claim that people would gain more weight if they didn’t diet[17].

(2) Another idea regarding dieting and obesity is that ”it’s not dieting itself that causes subsequent weight gain, but rather that people who are genetically prone to obesity are more likely to go on a diet[6].” In other words, even if the dieting is unsuccessful, the weight gain is attributed to genetic factors.

This claim was also contradicted by the results of a 10-year study on adolescents.

Among girls who were overweight at baseline (Time 1) and continued dieting or engaged in unhealthy weight control behaviors (such as skipping meals or eating very little) at both Time 1 and Time 2, BMI increased by 5.19 units over the 10-year period. In contrast, overweight girls who did not engage in any dieting or unhealthy weight control behaviors showed only a 0.15-unit increase in BMI. This suggests that dieting itself may have had a significant impact on weight gain[17].

In addition, a longitudinal twin study conducted in Finland examined weight changes in identical and fraternal twins who differed in the number of lifetime intentional weight loss episodes of more than five kg. The findings suggests that frequent intentional weight loss (dieting) may lead to weight gain over time, independent of genetic factors[16].

(3) Why is dieting a stronger predictor of weight gain among adolescents and individuals with a normal weight?

According to previous studies, many young people are concerned about their body shape and size due to social pressure to achieve an ideal lean figure[28]. Additionally, for individuals who are within the normal weight range (BMI under 25) but have recently experienced gradual weight gain, dieting is motivated by a fear of fatness rather than by a desire to become thin[29].

Several studies have pointed out the prevalence of unhealthy weight control behaviors among adolescents (especially girls), such as skipping meals, eating very little, using appetite suppressants or laxatives, vomiting, binge eating, and incidental exercise[17, 30].

A five-year longitudinal study of adolescents found that dieting was associated with an increase in binge eating (males and females), a decrease in breakfast consumption (males and females) , reduced intake of fruits and vegetables (females), and decreased physical activity (males). In other words, dieting among adolescents may actually increase the risk of unhealthy eating and activity behaviors, potentially leading to counterproductive patterns for long-term weight management[19].

(4) Clinical studies, starvation experiments

Weight overshooting in normal-weight subjects during experimental semi-starvation and the recovery period, has been documented in the classic Minnesota Starvation Experiment (1945–46) and the U.S. Army Ranger multi-stress experiments[31].

In the Minnesota study, healthy men with an average weight of 69.3 kg lost more than 25% of their body weight during six months of semi-starvation. However, during the ad libitum refeeding period following 12 weeks of restricted rehabilitation, a hyperphagic response (incessant sensation of desire to eat)persisted, and as a result, their weight eventually exceeded their pre-starvation level[32,33].

In more recent years, similar body weight and fat overshooting have also been reported in young men at the US Army Ranger School. They lost about 12% of their body weight during 8–9 weeks of training under multiple stressors, including energy deficit and sleep deprivation, but at week 5 in the post-training recovery phase, their body weight had overshot by 5 kg, primarily due to increased fat mass[34].

<Summary of this section>

● Some observational studies suggest that dieting itself, regardless of genetic factors, may predict an increase in BMI.

● Of particular concern for weight gain is unhealthy dieting in adolescents and normal weight individuals.

● Some researchers point out that unhealthy dieting is likely to encourage behavioral patterns that are counterproductive to long-term weight management.

● In long-term clinical studies involving severe caloric restrictions, weight overshooting has been observed after the restrictions were lifted.

4. Conclusion: My thoughts

Not all diets lead to weight gain.

Some people succeed in losing weight and keeping it off by adopting a healthy eating pattern that suits them—for example, starting the day with breakfast, eating a balanced diet, reducing refined carbohydrates and ultra-processed foods, increasing vegetable intake, and exercising.

For instance, a systematic review analyzing six prospective cohort studies on the Mediterranean diet found that adherence to the Mediterranean diet was inversely associated with the risk of overweight and obesity, as well as with weight gain over five years[35].

Photo Credit: Freepik (Photo by Katemangostar)

However, obesity prevention and treatment are still often discussed solely from the perspective of “eating fewer calories and burning more,” leading many people to choose low-fat diets, skip breakfast or lunch, or endure long hours of hunger with nothing but small portions of fast food.

In particular, some young people, driven by social pressure or a fear of fatness, resort to extreme calorie restriction—such as skipping meals or eating very little—which raises concerns about both their health and weight gain over time[17].

While it’s difficult to prove causality through observational studies, I believe that the behaviors (such as dietary restriction) practiced by some individuals may be contributing to overall weight gain at the population level.

From an evolutionary perspective, it makes sense that the body would conserve its energy stores by reducing energy expenditure during times of scarcity, such as famine, and then quickly replenish those stores (body fat) when food is abundant [36]. In modern societies where tasty, easily digestible foods—such as refined carbohydrates and ultra-processed foods—are widely available, I believe that extreme dietary restriction can sometimes backfire.

According to previous studies, weight loss through dietary restriction has been found to trigger a biological starvation response—accompanied by metabolic, hormonal, and neurological changes—[37]which may help explain why body weight can end up increasing beyond the pre-diet level.

In the next article, I’d like to discuss various mechanisms that may promote weight gain after weight loss, including my intestinal starvation theory.

<References>

[1] Methods for voluntary weight loss and control. NIH Technology Assessment Conference Panel. Ann Intern Med. 1992 Jun 1;116(11):942-9.

[2] Mann T et al. Medicare's search for effective obesity treatments: diets are not the answer. Am Psychol. 2007 Apr;62(3):220-33.

[3] Bacon L, Aphramor L. Weight science: evaluating the evidence for a paradigm shift. Nutr J. 2011 Jan 24;10:9.

[4]Cannon G, Einzig H. Dieting makes you fat. London: Century Publishing; 1983.

[5] Jacquet P et al. How dieting might make some fatter: modeling weight cycling toward obesity from a perspective of body composition autoregulation. Int J Obes (Lond). 2020 Jun;44(6):1243-1253.

[6] Hill AJ. Does dieting make you fat. Br J Nutr. 2004 Aug;92 Suppl 1:S15-8.

[7] Lowe MR. Dieting: proxy or cause of future weight gain? Obes Rev. 2015 Feb;16 Suppl 1:19-24.

[8] Cleland R et al. Commercial weight loss products and programs: what consumers stand to gain and lose. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2001 Jan;41(1):45-70.

[9] National Center for Health Statistics, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2018.

[10] Montani JP et al. Dieting and weight cycling as risk factors for cardiometabolic diseases: who is really at risk? Obes Rev. 2015 Feb;16 Suppl 1:7-18.

[11] Williamson DF et al. Weight loss attempts in adults: goals, duration, and rate of weight loss. Am J Public Health. 1992 Sep;82(9):1251-7.

[12]Serdula MK et al. Prevalence of attempting weight loss and strategies for controlling weight. JAMA. 1999 Oct 13;282(14):1353-8.

[13] Weiss EC et al. Weight-control practices among U.S. adults, 2001-2002. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Jul;31(1):18-24.

[14] Yaemsiri S et al. Perceived weight status, overweight diagnosis, and weight control among US adults: the NHANES 2003-2008 Study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011 Aug;35(8):1063-70.

[15] Piernas C et al. Recent trends in weight loss attempts: repeated cross-sectional analyses from the health survey for England. Int J Obes (Lond). 2016 Nov;40(11):1754-1759.

[16]Pietiläinen KH et al. Does dieting make you fat? A twin study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2012 Mar;36(3):456-64.

[17] Neumark-Sztainer D et al. Dieting and unhealthy weight control behaviors during adolescence: associations with 10-year changes in body mass index. J Adolesc Health. 2012 Jan;50(1):80-6.

[18] Stice E, Presnell K. Dieting and the eating disorders. In: Agras WS, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Eating Disorders. Oxford University Press; USA: 2010. pp. 148–179.

[19] Neumark-Sztainer D et al. Why does dieting predict weight gain in adolescents? : a 5-year longitudinal study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007 Mar;107(3):448-55.

[20]Viner RM, Cole TJ. Who changes body mass between adolescence and adulthood? Factors predicting change in BMI:1970 British Birth Cohort. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006 Sep;30(9):1368-74.

[21]Korkeila M et al. Weight-loss attempts and risk of major weight gain: a prospective study in Finnish adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999 Dec;70(6):965-75.

[22] Sares-Jäske L et al. Self-report dieting and long-term changes in body mass index and waist circumference. Obes Sci Pract. 2019 Mar 26;5(4):291-303.

[23] Kruger J et al. Attempting to lose weight: specific practices among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. 2004 Jun;26(5):402-6.

[24] Bild DE et al. Correlates and predictors of weight loss in young adults: the CARDIA study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996 Jan;20(1):47-55. PMID: 8788322.

[25] Coakley EH et al. Predictors of weight change in men: results from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998 Feb;22(2):89-96.

[26] French SA et al. Predictors of weight change over two years among a population of working adults: the Healthy Worker Project. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1994 Mar;18(3):145-54. PMID: 8186811.

[27] Chaput JP et al. Risk factors for adult overweight and obesity in the Quebec Family Study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009 Oct;17(10):1964-70.

[28]Field AE et al. Family, peer, and media predictors of becoming eating disordered. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008 Jun;162(6):574-9.

[29] Chernyak Y, Lowe MR. Motivations for dieting: Drive for Thinness is different from Drive for Objective Thinness. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010 May;119(2):276-81.

[30] Stice E et al. Naturalistic weight-reduction efforts prospectively predict growth in relative weight and onset of obesity among female adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999 Dec;67(6):967-74.

[31] Dulloo AG et al. How dieting makes some fatter: from a perspective of human body composition autoregulation. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012 Aug;71(3):379-89.

[32] Keys A et al. (1950) The Biology of Human Starvation. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

[33] Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Greystone Books, 2016, Pages 36-39.

[34]Nindl BC et al. Physical performance and metabolic recovery among lean, healthy men following a prolonged energy deficit. Int J Sports Med. 1997 Jul;18(5):317-24.

[35]Lotfi K et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet, Five-Year Weight Change, and Risk of Overweight and Obesity: A Systematic Review. Adv Nutr. 2022 Feb 1;13(1):152-166.

[36] van Baak M. Adaptive thermogenesis during over- and underfeeding in man. Br J Nutr. 2004 Mar;91(3):329-30.

[37] Mann T et al. Promoting Public Health in the Context of the "Obesity Epidemic": False Starts and Promising New Directions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015 Nov;10(6):706-10.

2022.11.11

Why Are Sumo Wrestlers So Fat?; Six Reasons They’ve Adapted to the Gut Starvation Mechanism

Contents

<Introduction>

- The same mechanism as people who rebound after dieting

- The six reasons that I believe it is a starvation mechanism

<The bottom line>

<Introduction>

Have you ever seen a sumo wrestler right in front of you? When I was working as a waiter at a hotel several years ago, there was a pep rally for sumo wrestlers, and I was able to see them up close.

Also, at the 2017 Osaka tournament in Japan, I observed the morning practice of a team and was allowed to sample their breakfast called "chanko."

I had a sample of "chanko."

I got the impression that they are big-boned, with steel-like muscles, and a lot of body fat on top of that.

Their average body fat percentage is said to be around thirty percent or more, but there are some wrestlers in the twenty percent range, not that different from the average person. They are like a mass of muscles.

It is generally believed in Japan that wrestlers will gain weight because they eat a lot and sleep well including taking naps, but I can explain that they have successfully adopted the mechanism of intestinal starvation.

1. The same mechanism as people who rebound after dieting

In Japan, the image of sumo wrestlers in particular may lead to the image that "eating more makes you fat," but I would like to explain that this is the same mechanism as "those who end up rebounding after dieting and gain more weight than before" or "those who gradually gain weight by skipping breakfast or having a late dinner.”

First of all, I'm going to illustrate how both of them gain weight in the figure below.

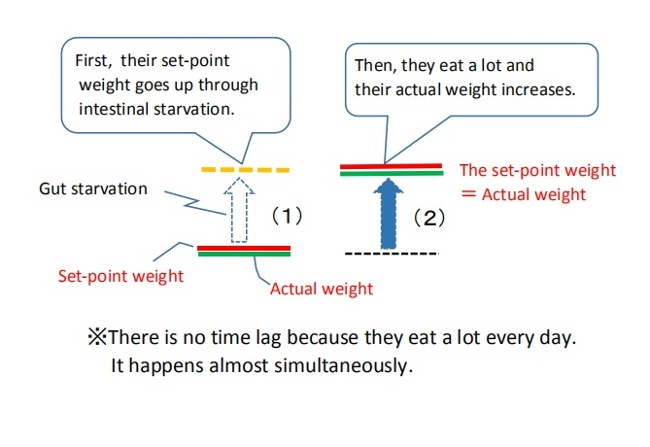

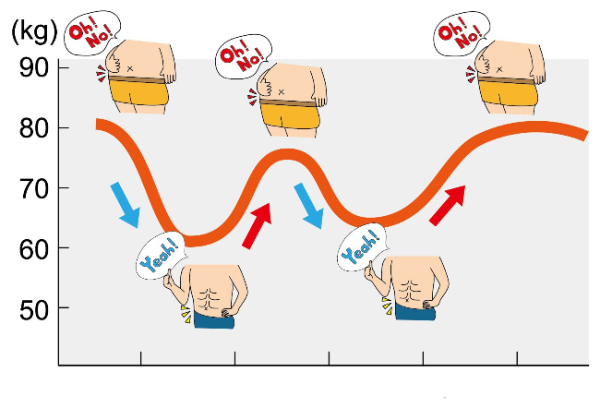

■The concept of a person who gains more weight than before after dieting

(1)→ (2)→ (3)

(1) You will lose a little weight through caloric restriction or exercising, etc.

(2) When you eat less (especially with an unbalanced diet), and you feel hungry for an extended period of time, you tend to starve your gut, and your set-point for body weight may go up without you realizing it.

(3) Later, when you start eating as you did before dieting, your weight will be higher than before.

■The concept of sumo wrestlers gaining weight

(1) → (2)

(1)First, by their traditional unique diet and hard practice, intestinal starvation can be induced. Their set-point weight goes up.

(2)Then, they eat a lot and thire actual weight increases (weight gain).

If you are a dieter, there is a time lag, but in the case of wrestlers, they eat good amounts of food every day, so it happens almost simultaneously.

Although they appear to eat a lot and are gaining weight, if intestinal starvation is not induced, their weight should not increase as much as expected.

2. The six reasons that I believe it is a starvation mechanism

When you see big eaters in a food eating competition, some may ask, "Why don't they get fat even though they eat so much?” But, from my theory, it is not at all surprising.

It’s not that they have a special "non-fattening constitution," but that anyone who eats like that from morning to night is less likely to gain weight (although I wonder why they can eat so much food at once).

Please understand that the way of eating of a sumo wrestler is a far cry from that of an eating competitor.

■An explanation of why the way of eating and exercising of sumo wrestlers can easily induce intestinal starvation. (1) - (6)

(1)A wrestler must weigh at least sixty-seven kilograms to be admitted. People who are overweight or muscular from the beginning tend to have stronger stomachs, and are thought to have a relatively high digestive rate. Such people are more likely to induce gut starvation than thin people.

(2) The basic diet for sumo wrestlers is called "chanko," which consists of easily digestible proteins such as chicken, fish, tofu, etc., and vegetables, slowly simmered in soy sauce. It is relatively low in fat and easy to digest.

(3) Sumo wrestlers generally eat a good amount of rice. By eating a lot of rice and soup, the stomach expands (the balloon effect), which leads to creating the dilution effect and push-out effect of food in the stomach.

[Related article]

(4)They traditionally eat two meals a day: the first meal is around eleven a.m. after morning practice, and dinner is around six p.m.

Since they practice from the early morning without breakfast, if dinner is finished at seven p.m., it means that they do not eat for about fifteen to sixteen hours until the next meal. It make sense to do intense morning training on an empty stomach to gain weight.

Of course, there are some wrestlers who try to eat snacks or supplements late at night in order to take in more calories, but my idea is that it makes easier to gain weight when they don't eat.

(5)Strength training is a force for gaining strength, and it ultimately works in the direction of weight gain. Eating two meals a day and exercising intensely will make sumo wrestlers gain more weight.

(6)Most of the food in the pot is eaten first by the top-ranked wrestlers. The lower-ranked wrestlers eat next, and lastly the new trainees.

The last people have to eat a big ball of rice and leftovers, which consists of only a little meat and most of the soup.

However, it is said that this kind of meal tends to make sumo wrestlers gain more weight.

The bottom line

(1)Sumo wrestlers are famous for being big and fat, but they do not gain weight because their daily caloric intake exceeds their daily caloric expenditure.

Their traditional diet and exercise makes sense in terms of weight gain in that it facilitates the creation of intestinal starvation.

(2)Intestinal starvation is more likely to be induced when a person who has a big body from the start eats relatively easily digestible foods with lots of carbohydrates (rice) and two meals a day.

(3)The mechanism by which wrestlers gain weight is the same as that of "people who diet and gain more weight than before due to the rebound effect.”

In the case of sumo wrestlers, since they eat a lot every day, this happens almost simultaneously, and they appear to eat a lot and gain weight.

2019.11.21

There Are Two Steps to Lose Weight the Right Way

-

Contents

-

- There are two ways to lose weight

- How to lower one's set-point weight

- What is your specific diet?

- Differences from low-carb diets

- The meaning of the “two-step"

- Health benefits

<The bottom line>

Although this is not a diet blog, since I’m writing the reasons why people gain weight, naturally, I thought about ways to lose weight, and I felt that I should write about it.

In this post, I will only write about my theory for losing weight. Please understand this is not based on practice, but I hope this will help someone.

1. There are two ways to lose weight

Just like the phrase “to gain weight” has two meanings, “to lose weight” also has two meanings.

【Related article】 The Two Distinct Processes Behind Weight Gain

(1) In the case you rebound

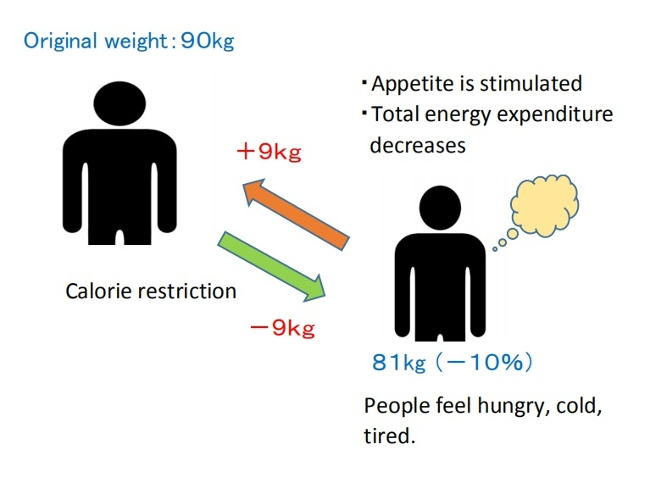

The first way is done by eating less and exercising more, as in conventional calorie-restricted diets. This method requires constant hunger.

The human body is thought to have a homeostatic function, and I use the "set-point" theory of body weight to explain its stable weight.

When food intake is significantly reduced and body weight decreases, the body perceives this as an energy crisis. In response, the body's protective metabolic mechanisms kick in to preserve energy stores, causing energy expenditure to drop significantly, more than expected[1,2]. Additionally, in my view, prolonged hunger increases the body's absorption rate as it tries to maximize nutrient intake.

Furthermore, the secretion of hormones that stimulate appetite increases, while the secretion of satiety hormones is suppressed[3]. You start feeling an overwhelming urge to eat.

In most cases, weight loss doesn't last long, and eventually, you rebound back to your original weight range.

In other words, attempts to sustain weight loss invoke adaptive responses involving the coordinate actions of metabolic, neuroendocrine, autonomic, and behavioral changes that ‘oppose’ the maintenance of a reduced body weight[4].

[Related article]

Dieting Doesn’t Work in the Long Run

(2) Lower the “set-point weight” itself

I believe that the problem of obesity lies in the body’s “set point” being higher than normal.

As I mentioned in (1), the fact that obese individuals show metabolic resistance to calorie-restricted diets suggests that, for some people, obesity is a natural physiological state[5]. Animal studies also support the view that obesity is a state of energy regulation at a higher set-point[5].

Therefore, in order to lose weight properly, it is necessary to lower the set-point itself that serves as the foundation for maintaining the current state. I will cite relevant literature on this topic.

"There appears to be a “set point” for body weight and fatness, and the problem in obesity is that the set point is too high.(*snip*)

There are two prominent findings from all the dietary studies done over the years.

First: all diets work. Second: all diets fail.

What do I mean?

Weight loss follows the same basic curve so familiar to dieters. Whether it is the Mediterranean, the Atkins or even the old fashioned low-fat, low-calorie, all diets in the short term seem to produce weight loss. Sure, they differ by amount lost–some a little more, some a little less. But they all seem to work.

However, by six to twelve months, weight loss plateaus, followed by a relentless regain, despite continued dietary compliance.(*snip*)

So all diets fail. The question is why.

Permanent weight loss is actually a two-step process. There is a short-term and a long-term (or time-dependent) problem. "

( Fung J. 2016. The obesity code. pages 62,215 )

2. How to lower one's set-point weight

I believe that the "long-term problem" Doctor Fung refers to is addressing the underlying cause of the elevated set-point and lowering the set-point itself without triggering the body's resistance mechanisms.

Specifically, instead of being hungry frequently, I believe that eating more fibrous foods (such as whole grains, high-fiber vegetables and nuts) and foods that take longer to digest, can help reduce hunger and gradually lower the set-point for body weight.

This is because, according to my theory, the primary cause of weight gain, which leads to an increase in the set-point, is due to the mechanism of intestinal starvation. In other words, we need to do the opposite of feeling hungry at the time.

Although I can't fully explain it at this point, I believe that when the intestines are filled with nutrient-rich, undigested food, such as fibrous vegetables, beans, and dairy products, it signals to the body that "there is still enough food."

As a result, the body doesn't perceive it as a crisis and doesn't trigger resistance mechanisms involving changes in metabolism or neuroendocrine responses.

Additionally, as hunger decreases, appetite diminishes, and absorption rates gradually decline. Eventually, I assume that body fat would decrease due to the coordinated actions between the brain—particularly the hypothalamus—and organs and peripheral tissues, etc.[6]

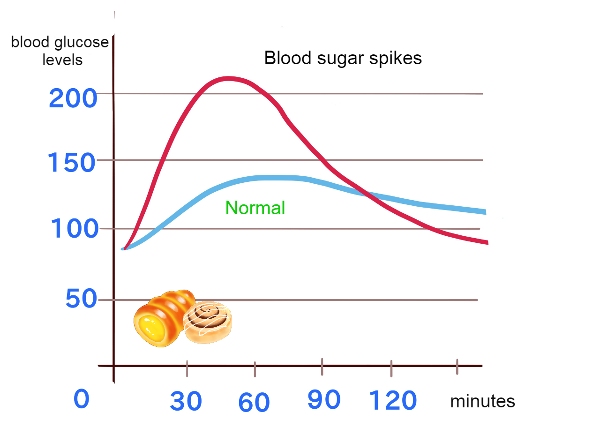

■It may be difficult to understand how eating food reduces absorption rate, but imagine, for example, eating a snack bread and a glass of orange juice.

If you eat it when you are starving, your blood glucose level will jump up, whereas if you eat it three hours after finishing a well-balanced lunch, your blood glucose level will not rise as much.

Even when you go out for drinks, if you haven't eaten anything for almost ten hours, you may get drunk faster, but if you eat a good lunch and have ice cream two hours before drinking, you will get drunk more slowly. In other words, if you keep eating less digestible foods and slow-digesting foods to reduce hunger, the absorption rate of food should decrease.

3.What is your specific diet?

I think the key is to reduce carbohydrate intake to a certain extent and conversely increase meat, fish, oil/fat, fibrous vegetables, seaweed, nuts, dairy products, etc. to reduce the time you feel hungry.

(If you feel a little hungry, eat something. Eat regularly even if you don't have an appetite.)

Specifically, I believe there are two ways to do this.

(1) The way to actually improve your diet

♦Reduce carbohydrate intake (rice, bread, noodles, etc.) by half to a third.

♦Eat low G.I. carbohydrates if possible, such as brown rice, whole-grain bread, cold rice (starch turns indigestible once cooled down) and al dente pasta.

♦Increase foods other than carbs such as meat, fish, fat/oil, dairy products, nuts, fibrous vegetables, seaweed, etc.

♦Avoid processed foods, fast food, and snacks as much as possible, and prioritize minimally processed foods.

♦Eat at least three meals a day, and if you feel hungry between meals, it's okay to have a snack.

♦Of course, you can combine this step with running or gym workouts, but since calorie burning is not the goal, it's better to consume something like milk before or after exercising.

<Regarding fat intake>

Fats are an important energy source for the body, and at the same time a cause of weight gain for some, but I believe that it is a food that can help us lose weight depending on how we eat it.

Fats have traditionally been considered 'fattening' because they have a high energy density of 9 kcal per gram. However, since fats take longer to digest, consuming them frequently can help sustain a feeling of satiety and, in my opinion, even contribute to weight loss. (Of course, it differs from person to person)

[Related article] Eating Fat/oil Can be a Deterrent to Gaining Weight

(2) Slow down the digestive enzymes

For those who digest food quickly and don't easily feel satiated no matter how much they eat, Method (1) may have limited effectiveness. In fact, some may even gain weight due to the extra calories consumed.

In my theory, having a 'higher set weight' is related to an increase in absorption efficiency. Additionally, as obesity levels increase, losing weight can become more difficult because they digest food quickly and their absorption rate doesn’t decrease easily. Therefore, Method (1) is not necessarily incorrect, in theory.

In a similar case, in addition to improving the diet, it may be helpful to take medication that, for example, slows down the digestive process for fats and proteins, or decreases one’s appetite.

By slowing down the working of the gastrointestinal tract or lowering the ability to digest food, undigested food will remain longer in the intestines, which will have the same effect as (1) above.

( Naturally, it must be done under a physician's guidance.)

4. Differences from low-carb diets

I can’t recommend extreme carb-cutting like the ketogenic diet, but I believe it ends up being similar to a low-carb diet in practice.

Advocates of low-carb diets claim that the real cause of weight gain is carbohydrates, which triggers insulin release, and that instead of limiting them, you can eat as many protein-and fat-rich foods as you like to make up for the calories.

In reality, however, it is not "you can eat" but rather "you have to" in order to lose weight.

If you reduce meat, fish, and fats/oils as well, you will feel hungry just like in a conventional calorie-restricted diet, and such diets do not work for long, as studies have shown.

My theory is that carbohydrates are only an indirect cause of weight gain making it easier to induce intestinal starvation. The key is that we should consume more fibrous foods and slow-digesting foods, leaving more undigested food in the intestines, to suppress hunger. So, while carbohydrates are not necessarily bad, I believe that cutting the amount of carbohydrates in the diet will be more effective.

Of course, it is possible that reducing glucose, which provides immediate energy, may speed up weight loss in the short term.

5. The meaning of the “two-step”

For those who have been dieting by eating less, their caloric intake may at least increase . So "eat more to lose weight" may sound fishy.

However, reducing caloric intake is not the final point.

・In the short term, you may not experience the dramatic weight loss that comes with calorie-restricted diets, but by slightly reducing caloric intake and eating more fibrous foods and slow-digesting foods to reduce hunger, there is a possibility of gradual weight loss.

・In the long term, by continuing this approach, I suspect that the signal that "there is enough food" may take hold, and through the interaction between the brain—especially the hypothalamus—organs, and peripheral tissues[6], the set-point weight itself may decrease, leading to a body that doesn't experience the rebound effect.

Currently, even some researchers who recognize the concept of a body’s set-point view obesity as an incurable chronic disease[7]. They state that lifestyle interventions and obesity medications do not permanently alter the body’s set point, so weight loss achieved through dieting is not sustained, and weight lost with medication tends to rebound once the treatment is stopped[7].

However, in my view, this is because calorie-restrictive diets are fundamentally flawed. By focusing so much on calorie reduction, dieting has come to be seen as a difficult process that means giving up one’s favorite foods and enduring hunger. This approach only activates the body’s resistance mechanisms.

6. Health benefits

Even if you don't lose much weight, the health benefits are immeasurable. For example, while vegetables, legumes, nuts, fermented foods, and dairy products contain some calories, I believe there's no need to worry about that.

As many nutritionists and gut health experts say, these foods are rich in vitamins and minerals, promote a healthy gut microbiome, improve gut health, boost immunity, and help prevent spikes in blood sugar. These benefits far outweigh the calorie content and likely help prevent and/or improve lifestyle diseases. Even minimally processed meats and seafood are essential, as they provide protein, fats, and minerals that are vital for the body.

The bottom line

(1)Just as the phrase "to gain weight" has two meanings, "to lose weight" also has two meanings.

To avoid rebounding, the set-point weight itself must be lowered.

(2)Lowering the set-point weight requires a two-step approach:

・In the short term, reducing refined carbohydrates and ultra-processed foods, etc., and conversely increasing less digestible foods and slow-digesting foods while adjusting caloric intake, can help reduce hunger and, in turn, may gradually lead to weight loss.

・In the long term, by continuing this approach, I believe that signals that "there is enough food" may permeate the body, which, through the interactions between the brain, digestive system, pancreas, and fat tissues, the set-point weight itself can be reduced, making the body less likely to rebound.

(3)As obesity levels increase, losing weight with diet alone may become more challenging.

I consider this is partly because they digest food quickly and don’t easily feel satiated, resulting in no reduction in absorption efficiency.

In such cases, administering medication to slow down digestive enzymes or reduce appetite might be effective for some patients with obesity.

(4)Even without significant weight loss, eating balanced meals regularly is beneficial for maintaining health and may help prevent and/or improve lifestyle-related diseases.

References:

[1]Hall KD, Guo J. Obesity Energetics: Body Weight Regulation and the Effects of Diet Composition. Gastroenterology. 2017 May;152(7):1718-1727.e3.

[2]Egan AM, Collins AL. Dynamic changes in energy expenditure in response to underfeeding: a review. Proc Nutr Soc. 2022 May;81(2):199-212. doi: 10.1017/S0029665121003669. Epub 2021 Oct 4.

[3] Jason Fung. 2016. The obesity code. Canada: Greystone Books, Page 62.

[4] Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL. Adaptive thermogenesis in humans. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010 Oct;34 Suppl 1(0 1):S47-55.

[5]Richard E. Keesey, Matt D. Hirvonen. Body Weight Set-Points: Determination and Adjustment. The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 127, Issue 9, 1997, Pages 1875S-1883S, ISSN 0022-3166.

[6]Wilson JL, Enriori PJ. A talk between fat tissue, gut, pancreas and brain to control body weight. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015 Dec 15;418 Pt 2:108-19.

[7]Garvey WT. Is Obesity or Adiposity-Based Chronic Disease Curable: The Set Point Theory, the Environment, and Second-Generation Medications . Endocr Pract. 2022 Feb;28(2):214-222.

2018.05.30

Why Do We Gain Weight even Though We Eat Small Portions of Food?

Contents

- A woman friend who eventually put on some weight

- A colleague who gained three kilograms in a year

- "Just reduce calories" is a mistake

It is said that the cause of weight gain is the caloric intake exceeding calories burned through metabolism and activity. For this reason, I see people dieting by only reducing the amount of food they eat, and putting up with being hungry over long hours.

For example, they eat only a rice ball and a piece of fried chicken, or a hamburger and a drink for lunch. These people say they are hungry but continue experiencing hunger for long periods of time.

In my opinion, people like this not only do not diet well, but they also tend to gain weight eventually.

1. A woman friend who eventually put on some weight

When I was working part-time at a restaurant in college, there was a woman who wasn’t that overweight, but she started dieting anyway.

She wasn’t slim, but she wasn’t overweight, either. To me, she looked healthy and fit. I thought she was okay as she was. But it seemed that she started dieting because she wanted to get slim.

Therefore, she only ate half of her meal, such as rice and meat/fish dish and never any vegetables. She was always saying, “I’m starving...” but continued experiencing hunger and stopped eating snacks.

As a result, not only did she not lose weight, but she also gained a little weight.

2. A colleague who gained three kilograms in a year

The same goes for my colleague, T, who worked as a cook in the kitchen at a nursing home. When I first met him, he was a stocky guy (about 170cm tall and 70 kilos).

He wasn’t overweight but he was on a diet, saying he had gained three kilos which shattered his previous weight level in the last year.

In his case, he was working before six a.m., but he hardly ever ate breakfast.

For lunch, he only ate a small bowl of rice and meat or fish. He almost never ate vegetable dishes such as salad and simmered vegetables (traditional Japanese vegetable stew).

He gained two more kilos in the following year.

3. "Just reduce calories" is a mistake

What's wrong with this is, that the people previously mentioned thought that in order to lose weight, they only needed to reduce calories from carbohydrates, meat, and fat, etc. Furthermore, they thought they had to be hungry in order to lose weight.

As a result, I can posit that intestinal starvation was induced because they didn’t consume fiber from vegetables, fat, and dairy products, etc. very much, causing the set-point weight to increase.

There are two ways in which the intestinal starvation mechanism occurs.

(1) Eating regular or big portions of an unbalanced meal, but not eating as often (e.g. skipping breakfast and eating two meals a day) and experiencing hunger over many hours.

(2)Eating small portions as seen in dieters or pregnant women, sometimes skewed towards digestible carbohydrates and protein, etc. Even if they eat three times a day, they often experience hunger over many hours.

In conclusion, whether you eat a good amount of food or a small portion of food, if your diet consists of mostly digestible carbs and some protein, an imbalance of food in the intestines remains the same. If you don’t eat anything else and experience hunger over many hours, it leads to the similar effect in view of creating intestinal starvation.

Eating vegetable dishes, dairy products and fat/oil, etc. is important with regards to preventing intestinal starvation, but those people in the previous examples were only conscious of caloric intake, and chose not to eat them.

2017.12.07

After Gaining Weight, We Eat Too Much and Do Less Exercise

-

Contents

-

<Prologue>

- Rats don’t get fat from eating too much

- Example of not enough exercise after getting fat

Prologue

"The experts who say that we get fat because we overeat or we get fat as a result of overeating - the vast majority - are making the kind of mistake that would (or at least should) earn a failing grade in a high-school science class.

They're taking a law of nature that says absolutely nothing about why we get fat and a phenomenon that has to happen if we do get fat - overeating - and assuming these say all that needs to be said."

(Gary Taubes. 2011. Why we get fat. New York: Anchor Books, Page 76.)

This is the foundation I started writing my blog on. I’m sure that there are at least a few researchers in the world who think the same way as I do.

Even if someone insisted that, “the Earth is going around the Sun” in the sixteenth or seventeenth century where "geocentric theory" was the prevailing thought, no one would have believed him.

Many should have argued that, “if the Earth is going around the sun, our heads should go around, too.” However, now, it’s common sense that the Earth is going around the sun.

In the same way, many might not believe me when I say, “people can gain weight by intestinal starvation and it is the fundamental cause of being overweight.” However, I believe it’s the truth.

1.Rats don’t get fat from eating too much

It is said that, “eating too much and not enough exercise are the causes of gaining weight,” but here is an interesting experiment that is related to it.

"In the early 1970s, a young researcher at the University of Massachusetts named George Wade set out to study the relationship between sex hormones, weight, and appetite by removing the ovaries from rats (females,obviously) and then monitoring their subsequent weight and behavior.

The effects of the surgery were suitably dramatic: the rats would begin to eat voraciously and quickly become obese.The rat eats too much, the excess calories find their way to the fat tissue, and the animal becomes obese. This would confirm our preconception that overeating is responsible for obesity in humans as well.

But Wade did a revealing second experiment, removing the ovaries from the rats and putting them on a strict postsurgical diet. (*snip*) The rats, postsurgery, were only allowed the same amount of food they would have eaten had they never had the surgery.

What happened is not what you'd probably think. The rats got just as fat, just as quickly. But these rats were now completely sedentary. They moved only when movement was required to get food. (*snip*)

The way Wade explained it to me, the animal doesn't get fat because it overeats, it overeats because it's getting fat. The cause and effect are reversed.

(*snip*)

The evidence that fat tissue is carefully regulated, not just a garbage can where we dump whatever calories we don't burn, is incontrovertible.(*snip*)

Those who get fat do so because of the way their fat happens to be regulated and that a conspicuous consequence of this regulation is to cause the eating behavior (gluttony) and the physical inactivity (sloth) that we so readily assume are the actual causes."

(Taubes. Why we get fat. Page 89-90, 93-4.)

<1970s>

Words of Bruce Birstrian who conducted a treatment of a low-calorie diet (600kcal/day) to thousands of obese patients at Harvard University of Medicine.

"Undereating isn't a treatment or cure for obesity; it's a way of temporarily reducing the most obvious symptom. And if undereating isn't a treatment or a cure , this certainly suggests that overeating is not a cause."

(Taubes. Why we get fat. Page 39.)

My experience is a little different from the rats’ story, but I want to tell of my experience that I gained weight not because of eating more.

When I was very thin, under forty kilograms, I couldn’t eat a lot since my stomach always felt heavy. Fatty foods and oily foods were the worst. I tried hard to gain weight, but I couldn’t.

One day, I realized that I could gain weight by eating only easy-to-digest foods (mainly carbs and a little meat) and experiencing being hungry for hours. So, I tried to eat light meals for breakfast and lunch, and I tried not to eat vegetables and fat very much until dinner. By doing so, I gradually gained weight. And when I weighed about fifty kilograms, I had more muscle and less discomfort in my stomach. I was able to eat more than before.

Those who didn’t know my experience told me, “You’re gaining weight because you’re eating more,” but that wasn’t true.

After my body adjusted to my new eating plan, I gained weight little by little by eating. As I gained weight, I gradually gained more muscle and my appetite increased. As a result, I was able to eat more than before. So, the reality was the other way around.

▽Maybe it’s easier for you to imagine with an extreme example.

Let’s say there is a big man who is three meters tall and weighs two-hundred-fifty kilograms. If he eats five times as much food as we do, we would not think that he has grown big because he eats so much. Rather, we would think, "He is able to eat that much because he is so big.”

"Just prior to the Second World War, European medical researchers argued that it is absurd to think about obesity as caused by overeating, because anything that makes people growーwhether in height or in weight, in muscle or in fatーwill make them overeat.

Children, for example, don't grow taller because they eat voraciously and consume more calories than they expend. They eat so muchーovereatーbecause they're growing."

(Taubes. Why we get fat. Page 9.)

2.Example of not enough exercise after getting fat

"Some people find it hard to get their head round the fact that aerobic exercise is not particularly effective for weight loss, even when faced with all the facts.

One reason for this is our experience of seeing physically fit and active individuals who are clearly lean.

Look at any elite long-distance runner or Tour de France cyclist and you're probably getting a glimpse of what it's like to have a single-digit body fat percentage. The automatic thought process is that exercise causes leanness.

However, could it that individuals who are naturally lean are simply more likely to end up as elite long-distance runners or cyclists? In other words, might their natural leanness cause certain people to be more active, rather than the other way round?

There's actually some evidence for this. In one piece of research, the relationship between physical activity and body fatness in children over a 3-year period was assessed. It was found that the more sedentary children were, the more fat they carried.

This is all to be expected, but because the study was conducted over a prolonged period the researchers were able to gauge whether sedentary behaviour preceded weight gain.

Actually, it did not. In reality, children accumulated fat first, and then became more sedentary.

The authors noted that this finding 'may explain why attempts to tackle childhood obesity by promoting PA [physical activity] have been largely unsuccessful'. "

(Jone Briffa. 2013. Escape the Diet Trap. London: Fourth Estate, Pages 223-4.)

I agree with this opinion, but I’d like to add my own opinion.

As Dr. Briffa said, I think it’s reasonable to think those who are slim aim to be marathon athletes or soccer players, etc. They at least know that they can eat a lot and not get fat. So they will eat whatever they want without hesitation, won’t they?

In other words, by eating balanced foods every meal, intestinal starvation doesn’t happen —by that, I mean their set-point for body weight doesn’t change—and they keep their current weight while getting a little more muscle.

On the other hand, when people stay at home, spending time relaxing with a book or watching television, or when doing office work or light physical labor, don’t they tend to eat less or lighter meals?

Sometimes, they may eat only light meals such as hamburgers, hot-dogs, or instant noodles for lunch. Since they don’t exercise, they don’t pay attention to eating balanced and nutritious meals.

If their diet leans toward easily digestible carbs and some protein and they are experiencing being hungry for hours, the intestinal starvation mechanism may occur and their set-point weight will go up. They end up gaining more weight.

To sum up, I’d like to say that not enough exercise or laziness won’t directly cause people to get fat. The intensity and amount of physical activity will affect the amount of food you eat as well as food choices.

2017.09.28

What Does It Mean to Eat Relatively Less?

Contents

- An example of judo

- An example of delivery center

- An example of food

<The bottom line>

I always felt something was wrong, when I was having lunch with my coworker K, who is about eighty kilograms. He said to me, “You have to eat more in order to gain weight”, because I was very thin.

However, he was eating the same thing as I was. It’s just that he had a little more rice than I.

Why It felt odd was that "K was eating relatively less" and " I was eating relatively more " in terms of quality and quantity.

1. An example of "judo"

First, I’d like to explain by using the Japanese sport of judo. There are usually wrestlers of forty-five, sixty, and up to ninety kilograms mixed weight groups at a practice.

The forty-five kilogram wrestler often works with those who are heavier than him, so he will be practicing relatively hard. In particular, if he practices with a ninety kilogram wrestler, there is twice the difference of weight, so it’s difficult to win.

On the other hand, for the ninety kilogram wrestler, it’s a practice which is relatively easy, since there are only those who weigh less than him. Even if they do the same practice, the level of challenge is different for each wrestler.

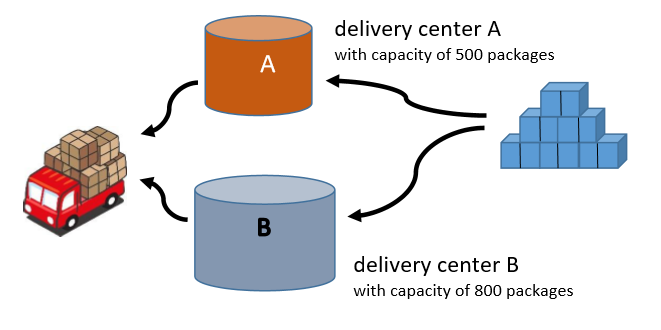

2. An example of delivery center

Let’s see it again here by using a “delivery center” example. A delivery center is a place where they sort packages and send them out everyday. There are two delivery centers. Center A has a capacity of five hundred packages, and delivery center B has a capacity of eight hundred packages.

When there are five hundred packages being processed, A will be at its limit, but B still has some room.

When there are seven hundred packages being processed, A is over its capacity, so employees have to work overtime, but B still has some room.

That is to say, even if the quantity of packages is the same, the things happening inside differ by their capacity. If this were food, then the package would be equivalent to the “intake amount of food.”

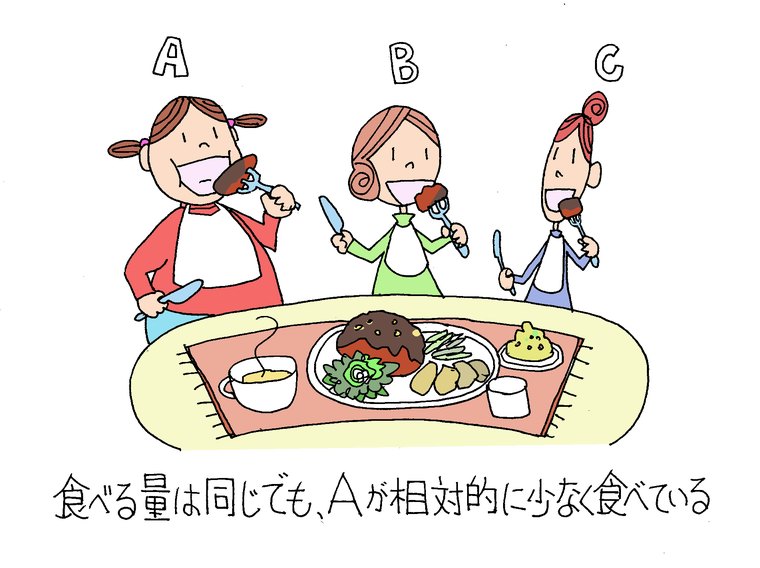

3. An example of food

I guess you already know what I want to say. Here again, we have three ladies of different weights eating the same thing. A: 90kg, B: 60kg, C: 45kg.

Let’s say all three had the same hamburger set for lunch.

In terms of the food intake, all of them have the same amount and calories, but when we take their weight into account, C, who is forty-five kilograms is eating relatively more, and A, who is ninety kilograms is eating a relatively light meal.

It’s because A who is ninety kilograms has a body twice as large as C, with a thicker chest and a bigger stomach. You can also say that she might have a stronger digestive ability compared to B or C.

Here, when we focus on body size, you can say, “A is eating quantitatively less." When we focus on digestive ability, “A is eating qualitatively simpler than C.

“Qualitatively” means that those with a stronger digestive ability can digest the same amount of food faster, even if they are the same body size. For example, it's been said that Caucasians generally have stronger digestive enzymes for protein and fat, compared to many Asian people.

Now, suppose A orders a large bowl of rice. Regarding intake amount, you might think, “after all, she must be fat because she eats a lot.”

However, if we take their weight into account, since rice is a carbohydrate which is easy to digest, it can be said that A is still eating relatively less and eating a lighter meal compared to B or C.

The bottom line

(1) Based on my intestinal starvation theory, people who have a bigger body or stronger digestion eat relatively less or lighter meals compared to thin people. They are more likely to feel hungrier, and depending on what they eat, they are prone to inducing intestinal starvation and gain more weight.

(2) Also, assuming that European, American, or African people generally have a stronger digestion for fat and protein compared to many Asian people, they are more likely to gain weight than many Asians, even if everyone eats the same. It’s not that they have particular obesity gene.

2017.06.10

Dieting (Eating Less and Exercising More) Doesn’t Work in the Long Run

-

Contents

-

- It has nothing to do with lack of willpower

- What was the long-term effect of dieting

- Cognitive dissonance

It is said that exercising and food restriction is necessary for losing weight. However, we rarely meet those who succeeded in dieting using such a method.

Japanese wrestler Bull Nakano (below) has repeatedly dieted and rebounded, but after having knee problems, it was imperative that she lose weight, so she had a gastrectomy to remove part of her stomach.

She said that “cutting the amount of foods and exercising didn’t make her thinner.”

Japanese comedian, Sugi-chan lost seven kilograms with Billy’s Boots Camp diet method, but rebounded to the same weight afterward.

In this article, I would like to introduce how conventional calorie-based diets are ineffective, based on two books: "Escape the Diet Trap" and "Why Do We Get Fat.”

Please note that most of these are quotations.

1.It has nothing to do with lack of willpower

"Ideas about what causes obesity vary. But you'll almost certainly be familiar with the idea that, at the end of the day, the problem is a product of caloric imbalance: specifically, the consumption of calories in excess of those burned through metabolism and activity. No doubt you'll also be familiar with the idea that the solution to your weight problem is simply to redress the balance by eating less and exercising more.

This advice seems to make sense. The trouble is, not only our collective experience but scientific research, too, shows that applying this advice hardly ever brings significant weight loss in the long term.

The usual explanation offered here is that those who fail with conventional tactics lack willpower and self-control. The reality, though, is that calorie-based strategies for slimming not only don't work, but simply can't work, for all but a small minority.

‘Escape the Diet Trap’ explores the reasons why traditional approaches to weight loss are a crashing failure. It reveals how eating less and exercising more causes the body to resist weight loss, and can actually predispose to weight gain over time."

(Jone Briffa. 2013. Escape the Diet Trap. Pages 1, 19.)

2.What was the long-term effect of dieting

"Limiting the studies to those where individuals were monitored for at least two years after the start of their efforts to lose weight allows us to assess the long-term success of these approaches. Many of us will know what it is to get a short-term win from eating less and exercising more but it's the long game we're interested in here.

<Study1>

Individuals with an average age of 36 and average BMI of 35.0 were prescribed a calorie-reduced diet (individuals ate about 1,000 calories less each day than the amount needed to maintain a stable weight).

Some of the individuals added exercise to this dietary restriction in the form of brisk walking for 45 minutes, 4-5 times each week.

The intervention lasted for a year, and weight was assessed another year after the end of the intervention.

Two years after embarking on a long-term (lasting at least a year) restrictive dietary regime, average weight loss was in the order of just 2 kg. Even when regular exercise is added, the weight loss still only averaged about 3 kg (about 6 lbs).

These outcomes look even more paltry when put in the context of the weight of many of the study participants. For someone of average height, a BMI of 35 works out at about 16 stone. I'd say it's unlikely that individuals of this weight would view a loss of a few pounds as a satisfying return on investment in terms of their diet and exercise efforts.

Another potential surprise is just how ineffective exercise was for the purposes of weight loss when employed as an adjunct to dietary restraint. The results from these studies suggest an additional loss of a mere 1 kg in those who were exercising regularly."

(Briffa. Escape the Diet Trap. Pages 20, 22-3.)

"Prescribing low-calorie diets for obese and overweight patients, according to a 2007 review from Tufts University, leads, at best, to “modest weight losses” that are “transient” – that is, temporary. Typically, nine or ten pounds are lost in the first six months. After a year, much of what was lost has been regained.

The Tufts review was an analysis of all the relevant diet trials in the medical journals since 1980. The single largest such trial ever done yields the very same answer. The researchers were from Harvard and the Pennington Biomedical Research Center, which is in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and is the most influential academic obesity-research institute in the United States.

Together they enrolled more than eight hundred overweight and obese subjects and then randomly assigned them to eat one of four diets. These diets were marginally different in nutrient composition (proportions of protein, fat, and carbohydrates), but all were substantially the same in that the subjects were supposed to undereat by 750 calories a day, a significant amount.

The subiecte were also given “intensive behavioral counseling” to keep them on their diets, the kind of professional assistance that few of us ever get when we try to lose weight.

They were even given meal plans every two weeks to help them with the difficult chore of cooking tasty meals that were also sufficiently low in calories.

The subjects began the study, on average, fifty pounds overweight. They lost, on average, only nine pounds. And, once again, just as the Tufts review would have predicted, most of the nine pounds came off in the first six months, and most of the participants were gaining weight back after a year.

No wonder obesity is so rarely cured. Eating less –that is, undereating–simply doesn't work for more than a few months, if that."

(Gary Taubes. 2011. Why We Get Fat. Page 36-7.)

3.Cognitive dissonance

"This reality, however, hasn't stopped the authorities from recommending the approach, which makes reading such recommendations an exercise in what psychologists call “cognitive dissonance,” the tension that results from trying to hold two incompatible beliefs simultaneously.

Take, for instance, the Handbook of Obesity, a 1998 textbook edited by three of the most prominent authorities in the field–George Bray, Claude Bouchard, and W. P. T. James.

“Dietary therapy remains the cornerstone of treatment and the reduction of energy intake continues to be the basis of successful weight reduction programs," the book says.

But it then states, a few paragraphs later, that the results of such energy-reduced restricted diets "are known to be poor and not long-lasting.” So why is such an ineffective therapy the cornerstone of treatment? The Handbook of Obesity neglects to say."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Page 37.)