Topics

08/15/2025

The Spread of Dieting May Be Fueling the Rise in Obesity

Summary

(1) Alongside the rising prevalence of being overweight and being obese, the prevalence of dieting has also steadily increased over the past several decades. There is concern that dieting may paradoxically be contributing to obesity.

(2) Several observational studies suggest that there is at least a partial causal relationship between dieting and weight gain, while some researchers argue that dieting is merely a proxy marker for a tendency to overeat.

(3) Some prospective studies have found that dieting for weight loss—particularly among adolescents, middle-aged women, and individuals within the normal weight range—is one of the strongest predictors of future weight gain. Social pressure to achieve an ideal slim body, along with a fear of fatness, may drive some people to engage in extreme calorie-restricted diets.

(4) In prospective studies of adolescents, the largest ten-year increases in BMI were observed in both males and females who consistently engaged in unhealthy weight control behaviors, such as skipping meals or eating very little.

Some researchers point out that dieting in adolescence is likely to promote behavior patterns—such as binge eating, skipping breakfast, and insufficient vegetable intake—that are counterproductive to long-term weight management.

<Conclusion>

(5) Some observational studies suggest that dieting itself, independent of genetic factors, may predict an increase in BMI. In long-term clinical studies such as starvation experiments, which involve severe caloric restriction, weight overshooting has also been observed after the restrictions were lifted.

(6) (My thoughts) Not all diets, but some forms of dietary restriction and unhealthy weight control behaviors—such as skipping meals—practiced by certain individuals may be contributing to overall weight gain at the population level.

(7) Weight loss through dietary restriction has been found to trigger a biological starvation response—accompanied by metabolic, hormonal, and neurological changes—which may help explain why body weight can end up higher than the pre-diet level.

【 Full Text 】

-

Contents

-

- Recent trends in dieting and obesity

- Problems and points to note in the observational study

- Is there a causal relationship between dieting and weight gain?

- Conclusion: My thoughts

<Introduction>

In recent years, more and more people around the world are going on diets to lose weight. However, some have raised concerns that dieting itself may be contributing to the rise in obesity.

For example, have you ever noticed that actresses or female TV announcers seem to have gained weight compared to how they looked in the past? To me, it’s hard to believe they’re simply overeating. On the contrary, I suspect they may actually be dieting—such as skipping meals or eating smaller portions—because they don’t want to gain weight.

In this article, I’d like to explore whether there is a link between the prevalence of dieting and the rise in obesity, based on findings from observational and clinical studies.

1. Recent trends in dieting and obesity

(1) In 1992, a panel of experts convened by the U.S. National Institutes of Health concluded: “With continued participation in weight-loss programs conducted in controlled settings, participants typically lose about 10% of their body weight. However, within one year after weight loss, one-third to two-thirds of the weight is regained, and within five years, almost all of it is regained [1].”

In addition, studies on long-term outcomes have shown that at least one-third of dieters regain more weight than they lost [2], raising concerns that dieting may paradoxically be promoting exactly the opposite of what it is intended to achieve[2,3].

(2) The notion that dieting to lose weight is counterproductive for weight control in that people may regain more fat than they lose through each cycle of weight loss/regain was embodied in the 1983 book “Dieting Makes You Fat[4].” Since then, whether dieting leads to weight gain remains a controversial and frequently debated topic among scientists [5,6,7].

(3) As of 1998, Americans spent over $33 billion annually on diet-related products and services [8]. Nevertheless, the prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 30) has steadily increased—from 30.5% in 2000 to 35.7% in 2010, and 42.4% in 2018 [9].

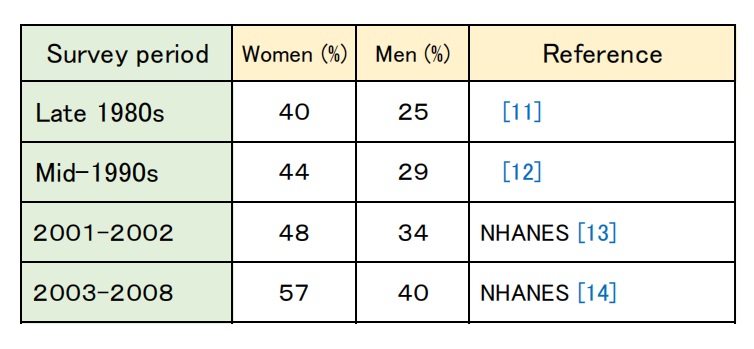

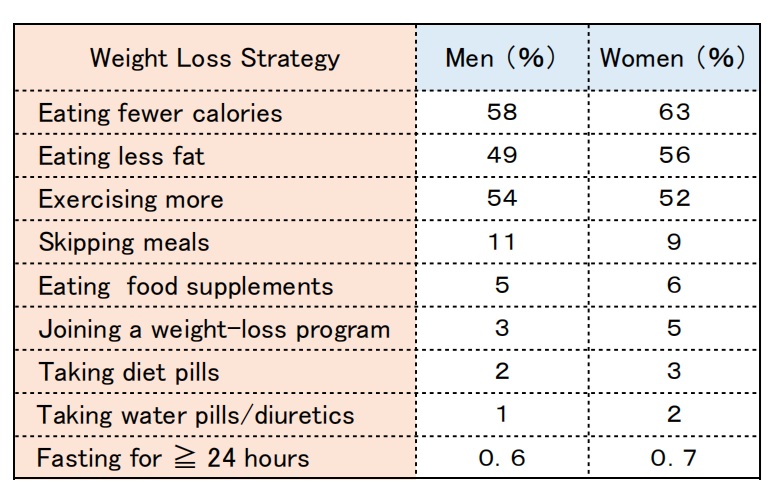

The prevalence of dieting has also continued to rise over the past several decades (see Table 1) alongside the increasing rates of obesity [10].

Table 1: Trends in the prevalence of dieting in the U.S.

In the United Kingdom as well, the age-standardized prevalence of weight loss attempts rose from 39% in 1997 to 47% in 2013.

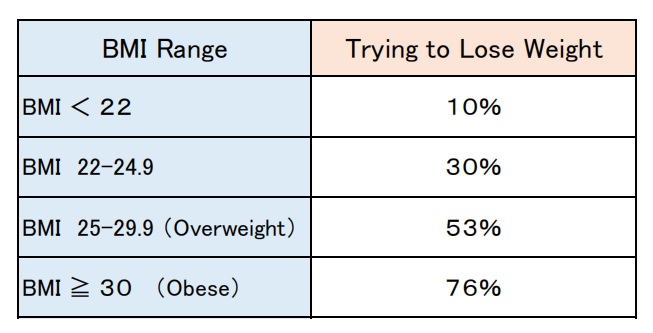

The number of people trying to lose weight has increased each year across all BMI categories [15].

Table 2: Prevalence of weight loss attempts by BMI category (2013,UK)

(4) While some researchers have suggested that the link between dieting and weight gain may be at least partially causal [16,17], others have argued that dieting is a proxy marker for a tendency to overeat and that without dieting, individuals would gain even more weight [18].

(5) Several prospective studies suggest that dieting to lose weight during adolescence [17,19,20], among middle-aged women [21], or by individuals who were initially within the normal weight range [5,21,22] are the strongest and most consistent predictors of future weight gain.

(6) A 10-year prospective study conducted in Minnesota (1998–2009) tracked dieting behaviors and BMI changes among adolescents every five years. A total of 1,902 participants (819 males and 1,083 females) completed the study.

Both males and females who consistently engaged in dieting and unhealthy weight control behaviors (such as skipping meals, eating very little, using food substitutes or diet pills) at both the start of the study (Time 1) and five years later (Time 2) had higher baseline BMIs, and showed greater increases in BMI after ten years (Time 3), as compared to those who did not diet.

Photo Credit: Freepik (photo by Prostooleh)

(*1) 43.7% of females and 18.7% of males reported persistent use (at both Time 1 and Time 2) of unhealthy weight control behaviors.)

In particular, "eating very little" and "skipping meals" were by far the most commonly reported behaviors, and both predicted statistically significant greater BMI increases in both females and males.

Of particular concern was that respondents who were overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30) at Time 1 and continued to engage in dieting or unhealthy weight control behaviors, showed substantial increases in BMI.

For example, overweight females who practiced unhealthy weight control behaviors at both Time 1 and Time 2 experienced an average BMI increase of 5.19 units over the 10-year study period, whereas those who did not use any unhealthy behaviors saw only a 0.15-unit increase [17].

(7) The 1998 U.S. National Health Interview Survey investigated the prevalence of weight loss strategies among U.S. adults (see Table 3).

Only one-third of those attempting to lose weight reported eating fewer calories and exercising more [23].

Table 3: The prevalence of weight loss strategies among U.S. adults (1998)

2. Problems and points to note in the observational study

While the majority of longitudinal observational cohort studies have shown subsequent weight gain among self-report dieters, some of the findings have suggested that dieting predicts both weight loss and weight gain, and the results have not always been consistent.

I would like to explore the possible reasons for this and other important points to consider.

(1) What kind of dieting was involved?

Many studies have examined whether participants were dieting or their history of dieting at the start, but not so many have investigated specific dieting behavior.

Of course, people who followed a healthy and sustainable approach to weight loss—e.g., eating more vegetables, reducing ultra-processed foods, eating breakfast, and exercising—may have been able to maintain their weight loss. On the other hand, those who followed the wrong kind of diet that only produced short-term results may have ultimately ended up failing.

(2) Study duration and timing of dieting

In some studies, dieting status was assessed only at the beginning, and changes in BMI were then tracked several years later (e.g., after 2, 5, or 10 years). However, from a homeostasis perspective, individuals who were dieting at the start of the study may already have had a body weight below their original weight (meaning set-point weight) .

Additionally, if someone begins (or stops) dieting during the study period, or starts dieting shortly before the study ends, it may be difficult to accurately determine the causal relationship between dieting and weight change.

(3) BMI tends to increase during adolescence

An increase in BMI does not necessarily mean an increase in body fat. During adolescence (from junior high through high school), muscle mass also increases significantly, so a certain amount of BMI gain is not unusual. This is something to keep in mind when conducting observational studies in this age group.

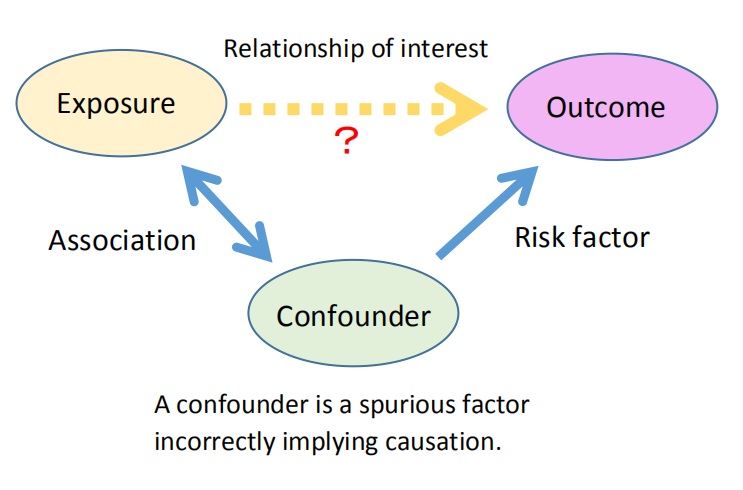

(4) Confounding factors

Confounding factors are variables that can influence the relationship between a specific exposure and an outcome.

For example, when studying the link between alcohol consumption and cancer, smoking is known to increase cancer risk as well. Since people who drink alcohol often smoke, smoking becomes a confounding factor.

When examining the causal relationship between dieting and obesity, it’s important to account for other potential confounding factors (*2).

(*2) For example: alcohol consumption, smoking cessation, lack of physical activity, insufficient intake of calcium or micronutrients, socioeconomic status, childbirth, and sleep deprivation are all associated with weight gain.

3. Is there a causal relationship between dieting and weight gain?

Throughout this blog, I’ve explained that calorie-restricted diets—such as skipping meals—may induce intestinal starvation, which could lead to weight gain-meaning an increase in the body’s set-point weight. So it’s not at all surprising that the rise in dieting may be linked to the rise in obesity.

However, this time, I’d like to set aside my own ideas and explore this causal relationship based on what can be interpreted from observational and clinical studies.

(1) First, let’s look at the claim that “dieting is merely a proxy marker for a tendency to overeat, and without dieting, people would gain even more weight.”

In the 10-year study of adolescents discussed in Section 1-(6), researchers were able to track the trajectories of those who were dieting at the start (Time 1) but either stopped dieting or continued dieting five years later (Time 2).

They found that those who stopped dieting gained significantly less weight compared to those who continued dieting. This finding does not support the claim that people would gain more weight if they didn’t diet[17].

(2) Another idea regarding dieting and obesity is that ”it’s not dieting itself that causes subsequent weight gain, but rather that people who are genetically prone to obesity are more likely to go on a diet[6].” In other words, even if the dieting is unsuccessful, the weight gain is attributed to genetic factors.

This claim was also contradicted by the results of a 10-year study on adolescents.

Among girls who were overweight at baseline (Time 1) and continued dieting or engaged in unhealthy weight control behaviors (such as skipping meals or eating very little) at both Time 1 and Time 2, BMI increased by 5.19 units over the 10-year period. In contrast, overweight girls who did not engage in any dieting or unhealthy weight control behaviors showed only a 0.15-unit increase in BMI. This suggests that dieting itself may have had a significant impact on weight gain[17].

In addition, a longitudinal twin study conducted in Finland examined weight changes in identical and fraternal twins who differed in the number of lifetime intentional weight loss episodes of more than five kg. The findings suggests that frequent intentional weight loss (dieting) may lead to weight gain over time, independent of genetic factors[16].

(3) Why is dieting a stronger predictor of weight gain among adolescents and individuals with a normal weight?

According to previous studies, many young people are concerned about their body shape and size due to social pressure to achieve an ideal lean figure[28]. Additionally, for individuals who are within the normal weight range (BMI under 25) but have recently experienced gradual weight gain, dieting is motivated by a fear of fatness rather than by a desire to become thin[29].

Several studies have pointed out the prevalence of unhealthy weight control behaviors among adolescents (especially girls), such as skipping meals, eating very little, using appetite suppressants or laxatives, vomiting, binge eating, and incidental exercise[17, 30].

A five-year longitudinal study of adolescents found that dieting was associated with an increase in binge eating (males and females), a decrease in breakfast consumption (males and females) , reduced intake of fruits and vegetables (females), and decreased physical activity (males). In other words, dieting among adolescents may actually increase the risk of unhealthy eating and activity behaviors, potentially leading to counterproductive patterns for long-term weight management[19].

(4) Clinical studies, starvation experiments

Weight overshooting in normal-weight subjects during experimental semi-starvation and the recovery period, has been documented in the classic Minnesota Starvation Experiment (1945–46) and the U.S. Army Ranger multi-stress experiments[31].

In the Minnesota study, healthy men with an average weight of 69.3 kg lost more than 25% of their body weight during six months of semi-starvation. However, during the ad libitum refeeding period following 12 weeks of restricted rehabilitation, a hyperphagic response (incessant sensation of desire to eat)persisted, and as a result, their weight eventually exceeded their pre-starvation level[32,33].

In more recent years, similar body weight and fat overshooting have also been reported in young men at the US Army Ranger School. They lost about 12% of their body weight during 8–9 weeks of training under multiple stressors, including energy deficit and sleep deprivation, but at week 5 in the post-training recovery phase, their body weight had overshot by 5 kg, primarily due to increased fat mass[34].

<Summary of this section>

● Some observational studies suggest that dieting itself, regardless of genetic factors, may predict an increase in BMI.

● Of particular concern for weight gain is unhealthy dieting in adolescents and normal weight individuals.

● Some researchers point out that unhealthy dieting is likely to encourage behavioral patterns that are counterproductive to long-term weight management.

● In long-term clinical studies involving severe caloric restrictions, weight overshooting has been observed after the restrictions were lifted.

4. Conclusion: My thoughts

Not all diets lead to weight gain.

Some people succeed in losing weight and keeping it off by adopting a healthy eating pattern that suits them—for example, starting the day with breakfast, eating a balanced diet, reducing refined carbohydrates and ultra-processed foods, increasing vegetable intake, and exercising.

For instance, a systematic review analyzing six prospective cohort studies on the Mediterranean diet found that adherence to the Mediterranean diet was inversely associated with the risk of overweight and obesity, as well as with weight gain over five years[35].

Photo Credit: Freepik (Photo by Katemangostar)

However, obesity prevention and treatment are still often discussed solely from the perspective of “eating fewer calories and burning more,” leading many people to choose low-fat diets, skip breakfast or lunch, or endure long hours of hunger with nothing but small portions of fast food.

In particular, some young people, driven by social pressure or a fear of fatness, resort to extreme calorie restriction—such as skipping meals or eating very little—which raises concerns about both their health and weight gain over time[17].

While it’s difficult to prove causality through observational studies, I believe that the behaviors (such as dietary restriction) practiced by some individuals may be contributing to overall weight gain at the population level.

From an evolutionary perspective, it makes sense that the body would conserve its energy stores by reducing energy expenditure during times of scarcity, such as famine, and then quickly replenish those stores (body fat) when food is abundant [36]. In modern societies where tasty, easily digestible foods—such as refined carbohydrates and ultra-processed foods—are widely available, I believe that extreme dietary restriction can sometimes backfire.

According to previous studies, weight loss through dietary restriction has been found to trigger a biological starvation response—accompanied by metabolic, hormonal, and neurological changes—[37]which may help explain why body weight can end up increasing beyond the pre-diet level.

In the next article, I’d like to discuss various mechanisms that may promote weight gain after weight loss, including my intestinal starvation theory.

<References>

[1] Methods for voluntary weight loss and control. NIH Technology Assessment Conference Panel. Ann Intern Med. 1992 Jun 1;116(11):942-9.

[2] Mann T et al. Medicare's search for effective obesity treatments: diets are not the answer. Am Psychol. 2007 Apr;62(3):220-33.

[3] Bacon L, Aphramor L. Weight science: evaluating the evidence for a paradigm shift. Nutr J. 2011 Jan 24;10:9.

[4]Cannon G, Einzig H. Dieting makes you fat. London: Century Publishing; 1983.

[5] Jacquet P et al. How dieting might make some fatter: modeling weight cycling toward obesity from a perspective of body composition autoregulation. Int J Obes (Lond). 2020 Jun;44(6):1243-1253.

[6] Hill AJ. Does dieting make you fat. Br J Nutr. 2004 Aug;92 Suppl 1:S15-8.

[7] Lowe MR. Dieting: proxy or cause of future weight gain? Obes Rev. 2015 Feb;16 Suppl 1:19-24.

[8] Cleland R et al. Commercial weight loss products and programs: what consumers stand to gain and lose. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2001 Jan;41(1):45-70.

[9] National Center for Health Statistics, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2018.

[10] Montani JP et al. Dieting and weight cycling as risk factors for cardiometabolic diseases: who is really at risk? Obes Rev. 2015 Feb;16 Suppl 1:7-18.

[11] Williamson DF et al. Weight loss attempts in adults: goals, duration, and rate of weight loss. Am J Public Health. 1992 Sep;82(9):1251-7.

[12]Serdula MK et al. Prevalence of attempting weight loss and strategies for controlling weight. JAMA. 1999 Oct 13;282(14):1353-8.

[13] Weiss EC et al. Weight-control practices among U.S. adults, 2001-2002. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Jul;31(1):18-24.

[14] Yaemsiri S et al. Perceived weight status, overweight diagnosis, and weight control among US adults: the NHANES 2003-2008 Study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011 Aug;35(8):1063-70.

[15] Piernas C et al. Recent trends in weight loss attempts: repeated cross-sectional analyses from the health survey for England. Int J Obes (Lond). 2016 Nov;40(11):1754-1759.

[16]Pietiläinen KH et al. Does dieting make you fat? A twin study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2012 Mar;36(3):456-64.

[17] Neumark-Sztainer D et al. Dieting and unhealthy weight control behaviors during adolescence: associations with 10-year changes in body mass index. J Adolesc Health. 2012 Jan;50(1):80-6.

[18] Stice E, Presnell K. Dieting and the eating disorders. In: Agras WS, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Eating Disorders. Oxford University Press; USA: 2010. pp. 148–179.

[19] Neumark-Sztainer D et al. Why does dieting predict weight gain in adolescents? : a 5-year longitudinal study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007 Mar;107(3):448-55.

[20]Viner RM, Cole TJ. Who changes body mass between adolescence and adulthood? Factors predicting change in BMI:1970 British Birth Cohort. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006 Sep;30(9):1368-74.

[21]Korkeila M et al. Weight-loss attempts and risk of major weight gain: a prospective study in Finnish adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999 Dec;70(6):965-75.

[22] Sares-Jäske L et al. Self-report dieting and long-term changes in body mass index and waist circumference. Obes Sci Pract. 2019 Mar 26;5(4):291-303.

[23] Kruger J et al. Attempting to lose weight: specific practices among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. 2004 Jun;26(5):402-6.

[24] Bild DE et al. Correlates and predictors of weight loss in young adults: the CARDIA study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996 Jan;20(1):47-55. PMID: 8788322.

[25] Coakley EH et al. Predictors of weight change in men: results from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998 Feb;22(2):89-96.

[26] French SA et al. Predictors of weight change over two years among a population of working adults: the Healthy Worker Project. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1994 Mar;18(3):145-54. PMID: 8186811.

[27] Chaput JP et al. Risk factors for adult overweight and obesity in the Quebec Family Study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009 Oct;17(10):1964-70.

[28]Field AE et al. Family, peer, and media predictors of becoming eating disordered. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008 Jun;162(6):574-9.

[29] Chernyak Y, Lowe MR. Motivations for dieting: Drive for Thinness is different from Drive for Objective Thinness. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010 May;119(2):276-81.

[30] Stice E et al. Naturalistic weight-reduction efforts prospectively predict growth in relative weight and onset of obesity among female adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999 Dec;67(6):967-74.

[31] Dulloo AG et al. How dieting makes some fatter: from a perspective of human body composition autoregulation. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012 Aug;71(3):379-89.

[32] Keys A et al. (1950) The Biology of Human Starvation. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

[33] Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Greystone Books, 2016, Pages 36-39.

[34]Nindl BC et al. Physical performance and metabolic recovery among lean, healthy men following a prolonged energy deficit. Int J Sports Med. 1997 Jul;18(5):317-24.

[35]Lotfi K et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet, Five-Year Weight Change, and Risk of Overweight and Obesity: A Systematic Review. Adv Nutr. 2022 Feb 1;13(1):152-166.

[36] van Baak M. Adaptive thermogenesis during over- and underfeeding in man. Br J Nutr. 2004 Mar;91(3):329-30.

[37] Mann T et al. Promoting Public Health in the Context of the "Obesity Epidemic": False Starts and Promising New Directions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015 Nov;10(6):706-10.