Topics

02/17/2023

Calorie Calculation: Why the Atwater Coefficient Is Not Perfect

-

Contents

-

- What is the Atwater coefficient in the first place?

- Digestion is an entirely different process than burning food

(I)~(V) - Perspective from my intestinal starvation theory

<Conclusions>

Many experts still believe that “one calorie is one calorie.” If we apply this idea to weight control, we have to only be concerned with the number of calories in our diet, regardless of what different foods we eat or how we eat them. Of course, the human body is not that simple, and many researchers have warned against this kind of thinking.

In explaining this, I thought I should make a distinction between reactions that occur "inside" the body (after absorption) and those that occur “outside" the body (before absorption) (*1).

In this article, I would like to consider the Atwater coefficient, which is the basis for calorie labels on food products, as an issue that occurs outside the body.

As many gut microbiologists recognize, the digestive organs such as the stomach and intestines are "external" to the body (e.g. bad bacteria in the gut do not directly harm the body), which is perfectly consistent with what I have been explaining in this blog-the idea that the "absorption rate is important."

( *1: "Diet-induced heat production" actually occurs after absorption, but it is related to digestion, so I’d like to also use it here to explain it as an external response.)

1. What is the Atwater coefficient in the first place?

In the 1800’s, chemists developed a method to measure the amount of calories in food by burning food and measuring the temperature change from its surroundings.

Burning food is chemically similar to the process by which our bodies break down food to obtain energy.

Much of what we know about food calories is said to come from the research in the late 19th century by Wilbur Atwater at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, who conducted a variety of experiments aimed at understanding human metabolism and the energy content of different foods.

By feeding volunteers various foods and calculating the difference in the heat of combustion between the food and the excreta, he approximated the calories absorbed by his volunteers. It is said that Atwater also took into account the dietary fiber which we can’t digest (*2), and proteins, some of which are excreted in the urine as urea after being absorbed.

More than one-hundred-twenty years after this experiment, these "Atwater coefficient" are still the basis for caloric calculations for all foods[1].

( *2: It is now known that dietary fiber produces some energy through fermentation and breakdown by the bacteria in the large intestine[2].)

Currently, the general Atwater coefficients of 4kcal/g for carbohydrate and protein, 9kcal/g for fat, and 7kcal/g for alcohol are applied to all foods regardless of the type of food.

The use of specific Atwater coefficient is also allowed, which is different for each food group[3].

2. Digestion is an entirely different process than burning food

We ingest food and then break down complex food molecules into simple structures such as glucose and amino acids by various digestive enzymes. After that, we get an energy source by absorbing them. Naturally, this is a completely different process compared to burning food in the laboratory.

According to Professor Rob Dunn (North Carolina State University), every calorie count on food labels is based on estimates or approximations, and are not an accurate reflection.

Recent research has revealed that how many calories we get from a given food depends on a variety of factors, including which species we eat, how we cook food, which bacteria are in our gut, and how much energy we use to digest different foods (diet-induced heat production).[4]

(I)Digestibility varies even in vegetables

Even if it is same vegetable group, they vary in the firmness of their leaves and stems. The cell walls of plant cells in the stems and leaves of some species are tough, whereas those of spinach, cucumber, and lettuce, etc. are soft and more than 90% of them are water.

Also, even in the same plant, the durability of cell walls can differ. The older the leaves, the tougher the cell walls tend to be and the more difficult they are to digest.

Seeds such as corn and nuts, in particular, have such sturdy cell walls that they can hoard precious calories within them and pass through the body intact[4].

A study by Janet A. Novotny at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (2012) found that when people eat almonds, they take in just 129 kcal per serving, not the 170 kcal listed on the label. It is beginning to be proven that nuts such as peanuts, almonds, and walnuts have a more robust cellular structure than other foods with similar levels of energy sources, and that their cell walls limit digestion. It is possible that the Atwater coefficient overestimates the digestibility of nuts.[5]

(II)Calories vary depending on how we cook food

Prof. Dunn also mentions that the biggest problem with modern calorie labels is that they failed to account for how food is prepared and processed, which dramatically changes the amount of energy derived from food.

We humans learned to cook raw food. We learned to process foods in different ways such as simmering, baking, frying, or even fermenting, to make them more palatable and tender.

This should have dramatically increased the calories we extracted from food [4].

Furthermore, some have pointed out that industrial food processing not only exposes food to high temperatures and pressures, but also softens food by adding air, to make it even easier to get more calories.

Corn, for instance, which is considered indigestible, is made into potage, and raw peanuts are roasted and processed into peanut butter. These processes must have dramatically increased the amount of energy available to the body. In other words, not all pork dishes are the same. The energy used for digestion and the absorption rate differ when roasting a chunk of pork versus making it into pâté.

(III)Energy required for digestion and immunity

Some research has shown that the energy required for digestion is not the same. This is called “diet-induced thermogenesis,” and it requires a great deal of energy to convert proteins into amino acids, fats into fatty acids, and carbohydrates into glucose. It is said that when proteins are broken down into amino acids, they require much more energy to digest than fats, because enzymes must unravel their tightly wound bonds[6].

It also differs between whole grains and refined wheat. A 2010 study found that people who ate 600-or 800-kcal portions of whole-wheat bread with sunflower seeds, kernels of grain, and cheddar cheese, expended twice as much energy to digest that food as those who ate the same amount of white bread and "processed cheese products.” Consequently, those who ate whole-wheat bread substantially obtained ten percent fewer calories, they said[7].

Many Japanese and Koreans traditionally love to eat raw fish or meat, if they’re fresh.

However, raw meat, for example, has been found to harbor many dangerous microbes, and our immune systems use energy to identify and deal with those pathogens[4].

It is possible that the same amount of cooked meat takes less energy to digest than steak tartare and has more usable calories .

(IV)Differences in digestive enzymes and intestinal bacteria

Most babies have lactase, an enzyme necessary to break down lactose sugar in milk, but it is said that most adults don’t produce this enzyme.

It has also been found that when starches such as rice and spaghetti are left to cool after being cooked, some of these starches crystallize into structures that digestive enzymes cannot easily break down.

What’s more, some microbes are present only in specific ethnic groups. Some Japanese, for example, have a microbe in their intestines which is suitable for breaking down seaweed. It has been found that these intestinal bacterium stole the seaweed-digesting genes from a marine bacterium that lingered in raw seaweed [4].

(V)There are variations for the method of calculation

The general Atwater coefficients were calculated based on the average daily diet of Americans at the time. Digestibility for carbohydrates, fats, and proteins were assumed to be 97, 95, and 92 percent respectively, and after adjusting a little for this, protein and carbohydrates were set at 4kcal/g, fats at 9kcal/g, and alcohol at 7kcal/g[8]. Although metabolizable energy values vary slightly for proteins, depending on whether they are vegetable or animal protein, and for carbohydrates, depending on whether they are sugar or starch, the coefficients were derived by a system of an average.

On the other hand, specific Atwater coefficients are also allowed, which divides food into several groups and applies a representative coefficient of that group to the entire group.

It is said that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) allows a total of five variations on the theme including these, and some point out that depending on the method chosen by the food company, there may be variation on the calorie labels[9]. When such uncertainties add up, the daily caloric intake could vary widely.

<Summary of this section>

Prof. Dunn mentions as follow:

(1) It is possible to modify the Atwater system for every food group, as in the almond example. However, this would require a challenge to reexamine the amount of nutrients retained in the excreta for every food.

(2) However, even if we completely revised calorie counts, they would never be accurate because how many calories we extract from food depends on a complex interaction between food, the human body, and its many microbes. In particular, the process of digestion is so complex that it is probably impossible to derive an accurate formula for calorie calculation that will suit everyone.

(3) Instead, we should think more carefully about the energy we get from food in the context of human biology. Processed foods are easily digested in the stomach and intestines, and thus provide a lot of energy for very little work. On the other hand, vegetables, nuts, and whole grains require more sweat to digest, offer far more vitamins and nutrients than processed foods, and keep our gut bacteria happy[4].

3. Perspective from my intestinal starvation theory

I believe that researchers and nutritionists at that time, including Atwater, were committed to ensuring that people could have an adequate amount of nutrition, and the calorie counting system they created had great merit. But I suspect it has been misperceived by some and is now causing problems with those who are overweight.

The reason why the issue of being overweight remains unresolved indefinitely is because many people are too fixated on the caloric value of foods.

Let's say you eat, as in the example in the section 2-[III], 400kcal of a meal: whole-wheat bread, nuts, and grilled chicken. Assuming that, after taking into account the energy required for digestion, you obtained ten percent fewer calories (360kcal), the argument that "wouldn't it be the same if you ate 360 kcal worth of white bread and chicken terrine?" is complete nonsense.

Fibers from whole-wheat bread and nuts tend to remain undigested in our intestines, which means there is a message to the body of "there is still food," but the combination of white bread and easily digestible protein, etc. is quickly digested, and if the "three factors + one" of my theory are met, the intestinal starvation message saying "there’s no food" would be sent to the brain through the small intestine.

In other words, you can gain weight despite a reduction in total daily caloric intake.

I I have been explaining throughout this blog that the fundamental difference between obese people and lean people can be explained by the difference in set-point weight, and that having a higher set-point weight is related to an increase in absorption efficiency, which is induced by intestinal starvation. In addition, since one of the key factors causing intestinal starvation is how fast you digest food, both digestion and absorption ability are extremely important in my theory.

Nevertheless, if we believe that only numbers based on averages of subjects are all we have, we ignore them. As Prof. Dunn mentions, I don’t believe that the complexity of digestion and absorption for a diverse population can be described by a system using an average.

(Please read the following article for other issues in "calorie counting.")

There is No Meaning in Simply Calculating Calories You Consume

Conclusions

The Atwater coefficients is a measure of how much energy we can obtain from food, but I think it is inadequate to address the problem of obesity. Even if we revised the Atwater coefficients more accurately by taking into account energy required for digestion and food composition, the obesity problem will not be solved if we judge things only by the number of calories.

One idea that has been suggested by some researchers is to introduce a "traffic-light" system on food labels, alerting consumers to foods that are highly processed (red dots), lightly processed (green dots) or in-between (yellow dots) [10], and I agree with this idea. It is also possible to combine satiety, the number of chews, and the indigestibility of food into this traffic-light system.

What we need now, I believe, is to take a little away from the apparent accuracy of "calorie counting," which seems more scientific, and rethink our traditional diets and eating habits.

This overlaps with what Prof. Dunn has also pointed out, but eating traditional fibrous vegetable dishes, unprocessed meat or fish, dairy products, fermented foods, and whole grain breads, etc., cannot be judged by caloric benefits alone.

Those foods contain far more vitamins and minerals than processed foods, and their fiber content keeps our gut bacteria in good condition, gives us moderate satiety, prevents rapid absorption of glucose, and provides many other health benefits. Depending on how you eat them, it should be possible to lose weight without worrying about caloric intake.

References:

[1]Giles Yeo. Calories on food packets are wrong–it's time to change that. 2021.

[2] Japan Food Research Laboratories. The Energy in Food. 2003.

[3] The Nutrition Coordinating Center (NCC). Primary Energy Sources.

[4] Rob Dunn. Science Reveals Why Calorie Counts Are All Wrong. 2013.

[5]Novotny JA et al. Discrepancy between the Atwater factor predicted and empirically measured energy values of almonds in human diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012 Aug;96(2):296-301.

[6]Westerterp KR. Diet induced thermogenesis. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2004 Aug 18;1(1):5.

[7]Barr SB, Wright JC. Postprandial energy expenditure in whole-food and processed-food meals: implications for daily energy expenditure. Food Nutr Res. 2010 Jul 2;54.

[8]Kazuko Takada. Absorption and Utilization of Energy in the Body. Physical Fitness Science. 2007, Pages 56, 288.

[9]Cynthia Graber, Nicola Twilley. Why the calorie is broken. BBC future. 2016.

[10]Richard Wrangham, Rachel Carmody. Why Most Calorie Counts Are Wrong. Harvard University. 2015.

12/18/2022

The Atkins Diet: What Were the Long-Term Effects of Weight Loss?

-

Contents

-

- What is the Atkins diet?

- Comparative study of various diets in weight loss

- What were the long-term results of the Atkins diet?

- Why was obesity rare among rice-eating Asians?

- Is the Atkins also ineffective for weight loss?

<The bottom line>

1. What is the Atkins diet?

The Atkins diet is a type of low-carbohydrate diet proposed by cardiologist Robert Atkins that restricts the amount of carbohydrates for energy and instead uses "fat" as an energy source. It is characterized by limiting carbohydrates to twenty to twenty-five grams per day for the first two weeks and then gradually increasing.

According to Dr. Fung, the author of “The Obesity Code,” Dr. Atkins weighed nearly one-hundred kilograms in 1963, and when he began working as a cardiologist in New York City, he needed to lose weight.

However, he couldn’t lose weight successfully on a conventional calorie-restricted diet, so he tried the low-carb diet based on the medical literature, which worked well as advertised, and he recommended it to his patients.

In 1972, he published "Dr. Atkins' Diet Revolution," which quickly became a bestseller.

At the time, it was said that the American Medical Association still considered high fat in the diet to be a cause of heart disease and stroke, and the "low-carb diet," which allowed people to eat as much meat and fat as they wanted, was not accepted.

Despite this, the low-carb diet’s popularity, rekindled in the 1990’s, led to a trend in the Atkins diet. In 2004, twenty-six million Americans said they were on some kind of low-carb diet .

New studies started appearing around 2005, comparing the Atkins diet to other diets that were once considered the standard, and what were the results[1]?

Let's take a look. I would like to express my thoughts on this at the end of this article.

2. Comparative study of various diets in weight loss

"In 2007, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a more detailed study: Four different popular weight plans were compared in a head-to-head trial.

One clear winner emerged-the Atkins diet. The other three diets (Ornish, which has very low fat; the Zone, which balances protein, carbohydrates and fat in a 30:40:20 ratio; and a standard low-fat diet) were fairly similar with regard to weight loss.

However, in comparing the Atkins to the Ornish, it became clear that not only was weight loss better, but so was the entire metabolic profile. Blood pressure, cholesterol and blood sugars all improved to a greater extent on Dr. Atkins's diet.

In 2008, the DIRECT (Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial) study reaffirmed once again the superior short-term weight reduction of the Atkins diet. Done in Israel, it compared the Mediterranean, the low-fat and the Atkins diets.

While the Mediterranean diet held its own against the powerful, fat-reducing Atkins diet, the low-fat AHA standard was left choking in the dust–sad, tired and unloved, except by academic physicians."

(Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Greystone Books, 2016, Pages 100-3.)

3. What were the long-term results of the Atkins diet?

"Longer-term studies of the Atkins diet failed to confirm the much hoped-for benefits.

Dr. Gary Foster from Temple University published two-year results showing that both the low-fat and the Atkins groups had lost but then regained weight at virtually the same rate. (*snip*)

A systematic review of all the dietary trials showed that much of the benefits of a low-carbohydrate approach evaporated after one year.

Greater compliance was supposed to be one of the main benefits of the Atkins approach, since there was no need for calorie counting.

However, following the severe food restrictions of Atkins proved no easier for dieters than conventional calorie counting.

Compliance was equally low in both groups, with upwards of 40 percent abandoning the diet within one year.

In hindsight, this outcome was somewhat predictable. The Atkins diet severely restricted highly indulgent foods such as cakes, cookies, ice cream and other desserts.

These foods are clearly fattening, no matter what diet you believe in. We continue to eat them simply because they are indulgent. (*snip*)The Atkins diet does not allow for this simple fact, and that doomed it to failure.

The first-hand experience of many people confirmed that the Atkins diet was not a lasting one. Millions of people abandoned the Atkins approach, and the New Diet Revolution faded into just another dietary fad. (The company Dr. Atkins founded in 1989 went bankrupt.)

But why? What happened?

One of the founding principles of the low-carbohydrate approach is that dietary carbohydrates increase blood sugars the most. High blood sugars lead to high insulin. High insulin is the key driver of obesity. Those facts seem reasonable enough. What was wrong?"

(Fung J. The Obesity Code. Pages 100-3.)

4. Why was obesity rare among rice-eating Asians?

Experts who advocate low-carbohydrate diets seem to think that carbohydrates cause weight gain because they eventually stimulate insulin secretion.

However, Dr. Fung mentioned that the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis is incomplete. Various problems are cited, but he raised the "paradox of the Asian rice eater" and the "diet of Kitava Island, in Papua New Guinea" as notable examples.

Most Asians have been eating a diet based on refined rice as their staple food for at least the last five decades; a study conducted in the late 1990’s found that carbohydrate intake in China and Japan was similar to or rather, higher than in the U.K. and the U.S.

Nevertheless, until recently, obesity was not a significant problem in both countries.

Also, according to a study conducted by Dr. Staffan Lindeberg in 1989 on the diet of the Kitava islanders, even though they were getting sixty-nine percent of their calories from carbohydrates such as yams, sweet potatoes and cassava, etc., their insulin levels were low and few people were obese[2].

Since Dr. Fung just mentioned the paradox of the Asian rice eater, I would like to mention this.

I am Japanese and was born in 1970, and I think that I should know how our diet has changed in the last five decades, and as a result, how obesity has increased in our society.

(This is explained in more detail in the following blog.)

[Related article] Why Does the Body Perceive That It Is More Starved than in the Past?

In short, I believe that carbohydrates are a contributing cause, but not the quantity itself.

Japan was basically an agrarian society, and rice cultivation has always been important. Until at least 40-50 years ago, I believe most Japanese people had eaten a lot of rice as it is called the staple food, but at the same time, they also ate a lot of fibrous vegetable dishes using roots or stems of plants, fermented soybean product called “natto,” and fish and meat dishes. Rice cakes called “mochi” and Japanese sweets as well.

At least in my family, my father was strict about family members eating meals three times a day at a regular time, every day.

I think the recent increase in the obesity rate in Japan can be explained due to a combination of many factors, including easily digestible carbohydrates such as bread and noodles, unbalanced diets with few vegetables, eating out, instant foods, and irregular life rhythms such as skipping breakfast or late dinners.

What I have seen in my experience is that many young women who go on a diet and then come off, some of them further increase their maximum weight.

(Irregular lifestyle)

I believe that the "three factors plus one" of my intestinal starvation theory can explain how the various factors intertwine, and how weight gain occurs. It's not just the amount of carbs eaten that matter.

5. Is the Atkins also ineffective for weight loss?

The "Do calories make people fat, or carbs?" concept is said to be a debate that has been going on since the 1800’s[3], and I think both are true in some ways, but neither is perfect.

If you reduce the amount of any energy source beyond what your body needs, it’s obvious that you will lose weight in the short term. However, if you go back to your original diet, in the long run, you will also regain the weight you had lost, as various studies have confirmed, and as most people who have been on a diet have probably realized.

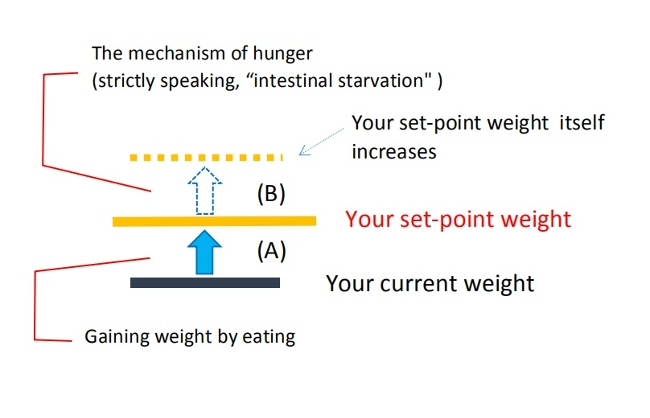

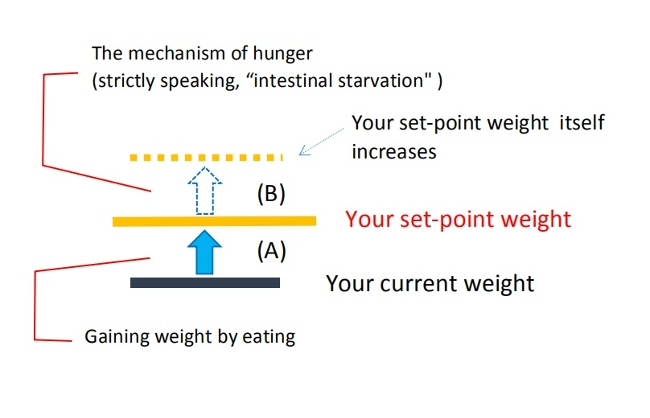

The reason for this is that the human body inherently has a homeostatic mechanism that drives it to return to its set point weight. So, the point is that in order to avoid rebounding, you must lower your set-point weight itself.

(For more details, please refer to the article below.)

[Related article] There Are Two Steps to Lose Weight the Right Way

In terms of this rebound in the Atkins diet in section three, I don't think it necessarily means that low-carb diets, including Atkins, are ineffective. I’m positive that it’s the one of the correct ways to lose weight.

However, if we focus too much on blood sugar and insulin levels, we lose sight of another important point.

What I mean is that the key to a low-carb diet, I believe, is not just reducing carbohydrate intake but also increasing foods that are less digestible and take longer to digest, such as fiber-rich foods, meat, fats, and dairy products.

When plenty of undigested food remains in the gastrointestinal tract, it helps to sustain a feeling of fullness and reduces hunger. In the long run, I think this approach can lower absorption rates. In particular, I believe fats and oils in the diet should not be reduced, but rather should be consumed regularly at every meal and even when having snacks.

Considering all of the above, I think that dieticians do not need to ban sweets such as chocolate, candy, ice cream, etc. so strictly. What’s most important is to make the diet sustainable without overburdening yourself, even allowing occasional indulgences in sweets.

The bottom line

(1) In the early 2000’s, the Atkins diet became a huge trend in the U.S., inspired by the low-carb diet that was rekindled in the 1990’s. In the short term, the Atkins method not only helped people lose weight, but it also significantly improved blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood glucose levels.

(2) However, in long-term studies, the subjects rebounded, as seen with low-fat diets. After one year from the end of the study, all the benefits of Atkins diets were gone.

Dr. Fung considered the "carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis" an incomplete theory. Carbohydrate intake itself was not the problem.

(3) My thoughts. If there is no change in your set-point for body weight, rebound can occur if you eat as you used to. In order to lose weight correctly, your set-point weight itself needs to be lowered.

(4) The key to a low-carb diet is not just controlling the amount of insulin released. It’s also important to reduce refined carbohydrates while increasing the intake of fiber-rich foods and those that take longer to digest.

When plenty of undigested food remains in the gastrointestinal tract, it helps sustain a feeling of fullness and alleviates hunger. Over time, I believe this approach can lead to a decrease in absorption rates.

<Reference>

[1] Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Greystone Books, 2016, Pages 96-99.

[2] Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Pages 103-105.

[3] Gary Taubes. Why We Get Fat. New York: Anchor Books, 2011, Pages 148-162.

11/11/2022

Why Are Sumo Wrestlers So Fat?; Six Reasons They’ve Adapted to the Gut Starvation Mechanism

Contents

<Introduction>

- The same mechanism as people who rebound after dieting

- The six reasons that I believe it is a starvation mechanism

<The bottom line>

<Introduction>

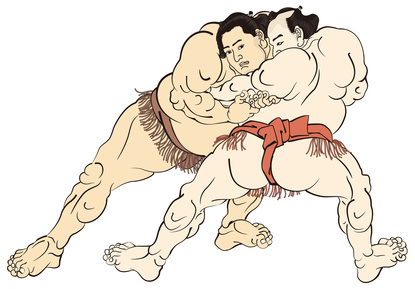

Have you ever seen a sumo wrestler right in front of you? When I was working as a waiter at a hotel several years ago, there was a pep rally for sumo wrestlers, and I was able to see them up close.

Also, at the 2017 Osaka tournament in Japan, I observed the morning practice of a team and was allowed to sample their breakfast called "chanko."

I had a sample of "chanko."

I got the impression that they are big-boned, with steel-like muscles, and a lot of body fat on top of that.

Their average body fat percentage is said to be around thirty percent or more, but there are some wrestlers in the twenty percent range, not that different from the average person. They are like a mass of muscles.

It is generally believed in Japan that wrestlers will gain weight because they eat a lot and sleep well including taking naps, but I can explain that they have successfully adopted the mechanism of intestinal starvation.

1. The same mechanism as people who rebound after dieting

In Japan, the image of sumo wrestlers in particular may lead to the image that "eating more makes you fat," but I would like to explain that this is the same mechanism as "those who end up rebounding after dieting and gain more weight than before" or "those who gradually gain weight by skipping breakfast or having a late dinner.”

First of all, I'm going to illustrate how both of them gain weight in the figure below.

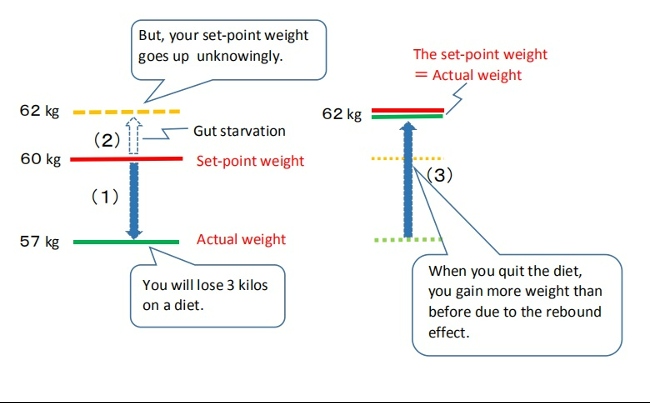

■The concept of a person who gains more weight than before after dieting

(1)→ (2)→ (3)

(1) You will lose a little weight through caloric restriction or exercising, etc.

(2) When you eat less (especially with an unbalanced diet), and you feel hungry for an extended period of time, you tend to starve your gut, and your set-point for body weight may go up without you realizing it.

(3) Later, when you start eating as you did before dieting, your weight will be higher than before.

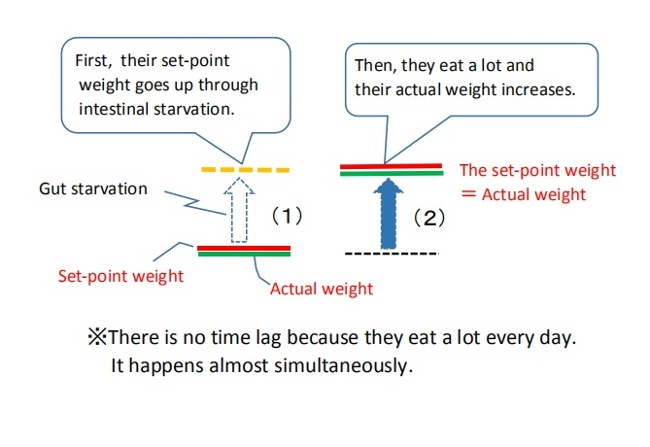

■The concept of sumo wrestlers gaining weight

(1) → (2)

(1)First, by their traditional unique diet and hard practice, intestinal starvation can be induced. Their set-point weight goes up.

(2)Then, they eat a lot and thire actual weight increases (weight gain).

If you are a dieter, there is a time lag, but in the case of wrestlers, they eat good amounts of food every day, so it happens almost simultaneously.

Although they appear to eat a lot and are gaining weight, if intestinal starvation is not induced, their weight should not increase as much as expected.

2. The six reasons that I believe it is a starvation mechanism

When you see big eaters in a food eating competition, some may ask, "Why don't they get fat even though they eat so much?” But, from my theory, it is not at all surprising.

It’s not that they have a special "non-fattening constitution," but that anyone who eats like that from morning to night is less likely to gain weight (although I wonder why they can eat so much food at once).

Please understand that the way of eating of a sumo wrestler is a far cry from that of an eating competitor.

■An explanation of why the way of eating and exercising of sumo wrestlers can easily induce intestinal starvation. (1) - (6)

(1)A wrestler must weigh at least sixty-seven kilograms to be admitted. People who are overweight or muscular from the beginning tend to have stronger stomachs, and are thought to have a relatively high digestive rate. Such people are more likely to induce gut starvation than thin people.

(2) The basic diet for sumo wrestlers is called "chanko," which consists of easily digestible proteins such as chicken, fish, tofu, etc., and vegetables, slowly simmered in soy sauce. It is relatively low in fat and easy to digest.

(3) Sumo wrestlers generally eat a good amount of rice. By eating a lot of rice and soup, the stomach expands (the balloon effect), which leads to creating the dilution effect and push-out effect of food in the stomach.

[Related article]

(4)They traditionally eat two meals a day: the first meal is around eleven a.m. after morning practice, and dinner is around six p.m.

Since they practice from the early morning without breakfast, if dinner is finished at seven p.m., it means that they do not eat for about fifteen to sixteen hours until the next meal. It make sense to do intense morning training on an empty stomach to gain weight.

Of course, there are some wrestlers who try to eat snacks or supplements late at night in order to take in more calories, but my idea is that it makes easier to gain weight when they don't eat.

(5)Strength training is a force for gaining strength, and it ultimately works in the direction of weight gain. Eating two meals a day and exercising intensely will make sumo wrestlers gain more weight.

(6)Most of the food in the pot is eaten first by the top-ranked wrestlers. The lower-ranked wrestlers eat next, and lastly the new trainees.

The last people have to eat a big ball of rice and leftovers, which consists of only a little meat and most of the soup.

However, it is said that this kind of meal tends to make sumo wrestlers gain more weight.

The bottom line

(1)Sumo wrestlers are famous for being big and fat, but they do not gain weight because their daily caloric intake exceeds their daily caloric expenditure.

Their traditional diet and exercise makes sense in terms of weight gain in that it facilitates the creation of intestinal starvation.

(2)Intestinal starvation is more likely to be induced when a person who has a big body from the start eats relatively easily digestible foods with lots of carbohydrates (rice) and two meals a day.

(3)The mechanism by which wrestlers gain weight is the same as that of "people who diet and gain more weight than before due to the rebound effect.”

In the case of sumo wrestlers, since they eat a lot every day, this happens almost simultaneously, and they appear to eat a lot and gain weight.

10/21/2022

People Who Usually Eat Less, and Who Occasionally Splurge, Gradually Gain Weight

Contents

- People who gained weight during the Covid self-quarantine period

- A wrong strategy is to skip a meal today because you ate too much yesterday

- Daily actions taken by people who are gradually gaining weight

<The bottom line>

1. People who gained weight during the Covid self-quarantine period

According to a survey, more than fifty percent of Japanese people put on some weight during the period of staying at home by government order to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

I saw a woman on television. She is a dance instructor and gained more than ten kilograms during this period.

Also, a friend of mine who owns a Japanese restaurant and works as a chef, gained almost five kilograms. He usually skipped breakfast and did not eat much dinner after his restaurant closed (around 11:00 p.m.), but during this period of self-quarantine, he stayed at home watching television and eating three times a day.

I think two classic examples of "eating a lot or stopping exercising makes you fat" fit here.

Normally, these people were under the strain of their jobs, moving all day long, eating in moderation, and paying attention to caloric intake. If that tension is gone and they simply exercise less and eat more, they will naturally gain weight.

However, this is the same pattern as rebounding, which means their weight go back to their set-point weight ([A] in Figure).

2. A wrong strategy is to skip a meal today because you ate too much yesterday

Sometimes I hear people say, "I ate too much at the all-you-can-eat buffet yesterday and gained three kilograms in one night.” They may have simply gained body fat or the weight of the food in their gut may also be a factor.

But It is a big mistake to say, "Okay, let's skip today's lunch."

Food ingested yesterday has already passed through the gastrointestinal tract and may be excreted in the form of a stool, but if you eat less today and put up with hunger over many hours, intestinal starvation may be induced, and your set-point weight may increase slightly.

So, it does not make sense to offset the extra calories you ate yesterday by eating less today.

3. Daily actions taken by people who are gradually gaining weight

With the recent gourmet food boom, many delicious foods are introduced on television and social media, while many people are worried about gaining weight and are trying to eat less.

Many of them usually restrain themselves as much as possible on the foods they want to eat, cutting back on calorie-dense foods such as sweets or fried foods.

Then, they splurge once in a while and eat their favorite foods as a reward.

In the end, they regret the weight they have temporarily gained and say, "Let's start dieting again tomorrow," and engage in a calorie-restricted diet.

I have no doubt whatsoever these diets are rarely successful. Rather, they tend to gain weight little by little. Eating on and off, or eating unevenly, is the first step toward becoming overweight.

If you skip meals or eat light meals (e.g. hamburgers and coffee) to reduce calorie and carbohydrate intake, you will deal with hunger for a longer period of time.

Even if you lose a little weight temporarily, the lack of fats/oils, dairy products, and fibrous vegetables can lead to intestinal starvation and an increase in your set-point weight over the long haul.

Unknowingly, your set-point weight may go up, and one day, when you eat like you used to, you may find that you have reached your highest weight ever. And it will be harder to lose weight than before.

The gastrointestinal tract starts by eating breakfast, and the food we eat is delivered to the rectum in around twenty hours or more (it differs from person to person).

Therefore, it is a mistake to say, "I ate too much yesterday, so I will skip lunch today," or "I ate a lot of fibrous vegetables yesterday, so I don't need them today.”

It is also a mistake to say, "I will eat enough vegetables and nutritious foods at dinner, so I will go with a light breakfast and lunch," because a combination of easily digested food can result in intestinal starvation in as little as six to eight hours.

The first step in becoming leaner is to eat three well-balanced meals religiously every day.

Even if you want to reduce total caloric and carbohydrate intake, be sure to consume a variety of foods from a diverse group of foods.

The bottom line

(1) Some people claim to have gained a few kilos during the Covid self-quarantine period, but I believe most cases can be explained by a return to one’s set-point weight as well as a rebound effect after dieting.

(2) The idea of adjusting for yesterday's excess calories by eating fewer calories today is a mistake when it comes to maintaining a stable weight in the long run.

(3) People who usually eat less and hold back on the foods they want to eat for dieting, and occasionally splurge on treats, are more likely to gain weight over the long haul.

Irregular eating, where a person eats on and off, can cause intestinal starvation when dealing with hunger over many hours, unknowingly increasing their set-point weight.

(4) Since the gastrointestinal tract basically begins with breakfast and the food we eat reaches the rectum in around twenty hours or so (it differs from person to person), it is important to eat three well-balanced meals every day if you do not want to gain weight.

10/10/2022

Does Obesity Run in the Family or Is It Due to the Living Environment?

Contents

- What was the relationship of weight between adoptees and adoptive parents?

- What was the weight of the twins raised apart?

- What do we consider a change in environment?: My thoughts

- Will the shape of your body from childhood continue?

<The bottom line>

Is obesity inherited from parents?

Let us recall our classmates in elementary school. To some extent, we can imagine, if not one hundred percent, that if the parents are thin, their children are often thin, and if the parents are fat, their children are often fat.

The question here is whether this is due to genetics or due to the living environment. Here is one such study I’d like to introduce.

1. What was the relationship of weight between adoptees and adoptive parents?

"Obese children often have obese siblings. Obese children become obese adults. Obese adults go on to have obese children. Childhood obesity is associated with a 200 percent to 400 percent increased risk of adult obesity. This is an undeniable fact. (*snip*)

Families share genetic characteristics that may lead to obesity. However, obesity has become rampant only since the 1970s. Our genes could not have changed within such a short time. Genetics can explain much of the inter-individual risk of obesity, but not why entire populations become obese.

Nonetheless, families live in the same environment, eat similar foods at similar times and have similar attitudes. Families often share cars, live in the same physical space and will be exposed to the same chemicals that may cause obesity–so-called chemical obesogens. For these reasons, many consider the current environment the major cause of obesity.

Conventional calorie-based theories of obesity place the blame squarely on this “toxic" environment that encourages eating and discourages physical exertion. Dietary and lifestyle habits have changed considerably since the 1970s (e.g. car, television, computer, fast food, high-calorie food, sugar, etc.).

Therefore, most modern theories of obesity discount the importance of genetic factors, believing instead that consumption of excess calories leads to obesity. Eating and moving are voluntary behaviors, after all, with little genetic input.

So-exactly how much of a role does genetics play in human obesity?"

(Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Greystone Books, 2016, Page 21-2.)

"The classic method for determining the relative impact of genetic versus environmental factors is to study adoptive families, thereby removing genetics from the equation.(*snip*)

Dr. Albert J. Stunkard performed some of the classic genetic studies of obesity. Data about biological parents is often incomplete, confidential and not easily accessible by researchers. Fortunately, Denmark has maintained a relatively complete registry of adoptions, with information on both sets of parents.

Studying a sample of 540 Danish adult adoptees, Dr. Stunkard compared them to both their adoptive and biological parents.

If environmental factors were most important, then adoptees should resemble their adoptive parents. If genetic factors were most important, the adoptees should resemble their biological parents.

No relationship whatsoever was discovered between the weight of the adoptive parents and the adoptees.(*snip*)

Comparing adoptees to their biological parents yielded a considerably different result. Here there was a strong, consistent correlation between their weights.

The biological parents had very little or nothing to do with raising these children, or teaching them nutritional values or attitudes toward exercise. Yet the tendency toward obesity followed them like ducklings. When you took a child away from obese parents and placed them into a "thin" household, the child still became obese.(*snip*)

This finding was a considerable shock. Standard calorie-based theories blame environmental factors and human behaviors for obesity. Environmental cues such as dietary habits, fast food, junk food, candy intake, lack of exercise, number of cars, and lack of playgrounds and organized sports are believed crucial in the development of obesity. But they play virtually no role."

(Fung. The Obesity Code. Pages 22-3.)

2. What was the weight of the twins raised apart?

"Studying identical twins raised apart is another classic strategy to distinguish environmental and genetic factors. Identical twins share identical genetic material, and fraternal twins share 25 percent of their genes.

In 1991, Dr. Stunkard examined sets of fraternal and identical twins in both conditions of being reared apart and reared together. Comparison of their weights would determine the effect of the different environments.

The results sent a shockwave through the obesity-research community. Approximately 70 percent of the variance in obesity is familial.(*snip*)

However, it is immediately clear that inheritance cannot be the sole factor leading to the obesity epidemic.

The incidence of obesity has been relatively stable through the decades. Most of the obesity epidemic materialized within a single generation. Our genes have not changed in that time span.

How can we explain this seeming contradiction?"

(Fung. The Obesity Code. Pages 23-4.)

3. What do we consider a change in environment? : My thoughts

I think this is a very interesting study because it compared data from biological parents and adoptive parents.

However, can we assert from the results of this one alone that the influence of genetics was much greater and environmental factors were much less significant?

I believe, as Doctor Fung mentions, the rapid increase in obesity in recent years (since about 1970) has much to do with changes in our living environment (what we eat, irregular lifestyle,etc.),not the genes.

Even those who were slim in their youth may gain five or ten kilos in a short period of time at a certain age, triggered by something (living alone, marriage, parenting, stress from work, etc.). Some people put on weight every time they try dieting to lose weight.

In other words, many of us, in our hearts, have probably noticed that changes in eating habits or our living environment can change our body shape.

■What is the "change in environment" that causes a change in weight here?

The study considers a child living with adoptive parents or twins raised separately to be a "change in living environment," but I think there is a problem with this study.

If a family can afford to take in a child as adoptive parents, don't they have some money to spare and feed their adoptee a somewhat balanced diet three times a day?

Although what they eat and caloric intake may differ from family to family, those changes are not necessarily "environmental changes" that cause changes in weight. Just because the adoptive parents are thin does not mean that adoptees will become thin even if they eat the same diet.

On the contrary, I believe that a fundamental increase in weight and body shape occurs when one’s set-point weight itself goes up, which is induced by intestinal starvation.

And since at least three (+one) factors are required to induce intestinal starvation, living with adoptive parents alone does not necessarily alter one’s set-point weight.

[Related article]

In Japan over the past few decades, our traditional eating habits have been declining. Instead, Westernized eating and diverse work styles have become more prevalent.

Amid these changes, intestinal starvation is more likely to be induced when unbalanced diets (high in easily digestible carbohydrates and ultra-processed foods, and with a lack of vegetables, etc.) combines with irregular lifestyle habits (skipping breakfast, eating late at night, etc.).

This is what I would like to call the "environmental factors and human behaviors" for the recent obesity epidemic, and while genetic factors are, of course, undeniable, I believe that environmental factors are quite significant.

4. Will the shape of your body from childhood continue?

One thing to note here is that the body shape in childhood (say, around three to five years old) tends to continue into adulthood.

When I think back to my classmates in first and second grade, the girls and boys who were fat (although they were not big eaters) often have a similar body shape even decades later.

From my theory, that means that their set-point weight has not changed, and in this study, if there are no environmental factors that cause changes in their set-point for body weight, then wouldn't the body shape from childhood basically continue?

But, I’m simply wondering what the childhood body shape is due to? Whether it is genetic factors or the way food is prepared during childhood-including weaning-is a question that remains unanswered.

The bottom line

(1) In a study regarding adoptive families and examining how genetic and environmental factors influence being overweight, no correlation was found between the weight of adoptive parents and that of their adoptees. On the other hand, when the adoptees were compared to their biological parents, there was a consistent correlation between the weight of both.

A study of twins raised separately also concluded that "genetic influences are far more significant.”

(2) Many researchers had previously blamed "environmental factors and individual behavior” for the recent obesity epidemic, but this study concluded that genetics had far more impact than environmental factors.

However, I find this study problematic. The fact of children living with adoptive parents or twins raised separately is not necessarily an environmental factor that causes changes in weight.

(3) Of course, I do not think we can ignore the genetic factor, but I believe that the recent obesity epidemic is caused by a combination of what we eat-westernized diets, refined carbohydrates, processed foods, etc.-plus lifestyle changes.

A major change in weight and body shape occurs when one’s set-point weight goes up, which is induced by intestinal starvation.

(4) If there is no significant change in one's set-point weight, I think the body shape from childhood is expected to continue. However, I 'm uncertain what determines childhood body shape, whether it is heredity or the way food is prepared during childhood, including weaning.